(5 / 5)

(5 / 5)

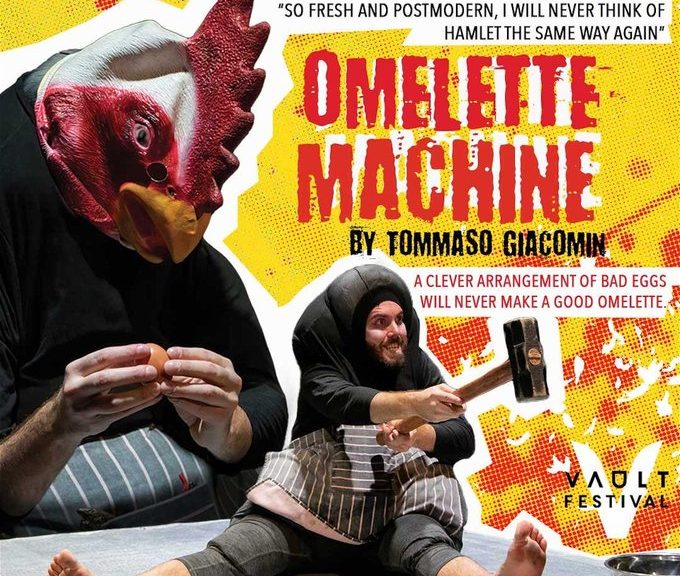

Theatre is very much a powerful tool to highlight topics of the time, to create political commentary and express the injustices and emotions of people. With the last 3 years adding to the feeling of the world getting seemingly worse, there’s something to be said of a production that makes these comments but encourages us to see the humility of it all.

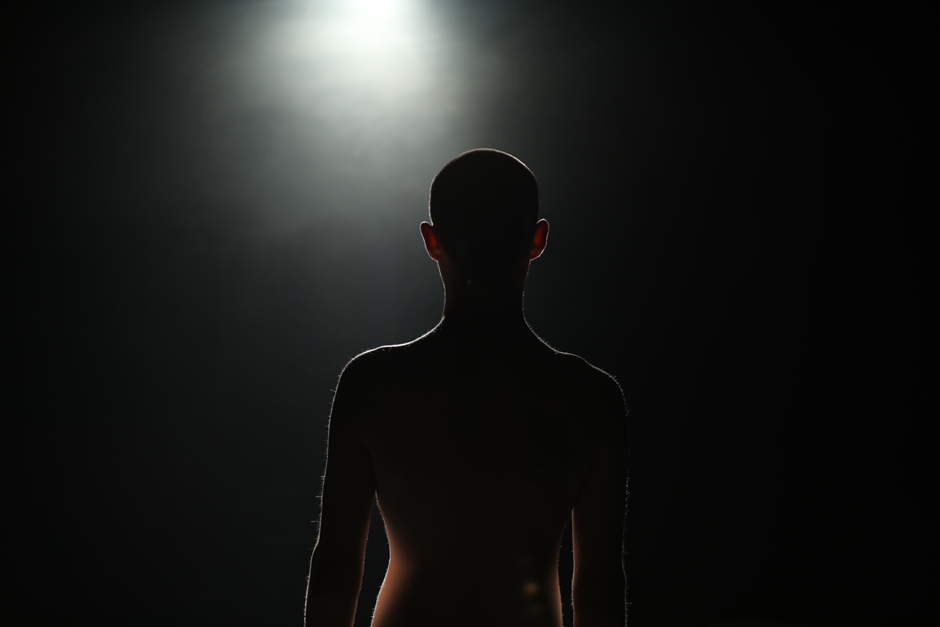

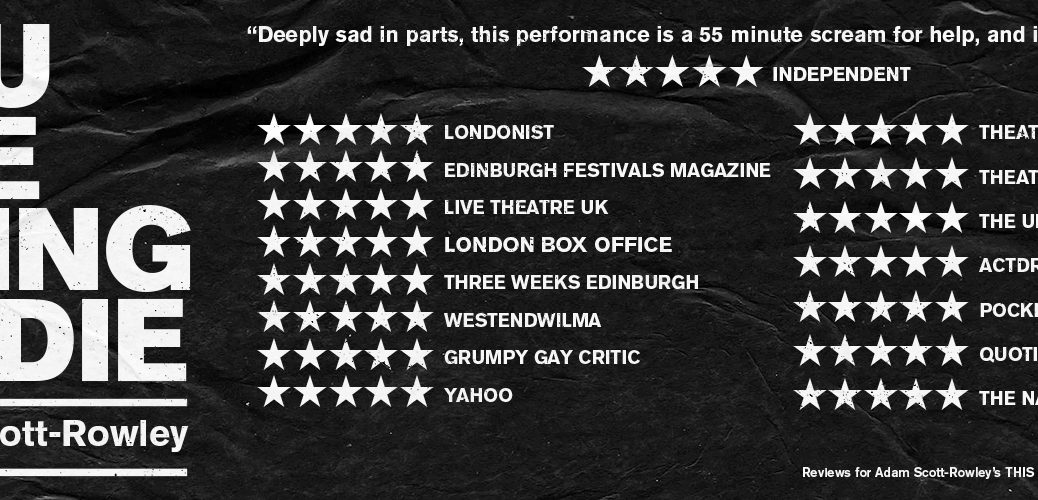

Adam Scott-Rowley’s, YOU ARE GOING TO DIE, does just this. Featuring Scott-Rowley completely in the nude, he vulnerably cycles through different ages, different people, thoughts and attitudes to give a holistic view of our world, of growing older and of experiencing oneself in a climate slowly getting worse. He creates highs and lows of comedy vs reflection, of matter of fact hilarity vs deep emotion which is poignant and effective; a emotional and thought provoking rollercoaster.

The action is already started as we take our seats; Scott-Rowley sat on a lit up toilet, with music and lights that make you feel as if you are entering a Berlin rave club, there’s this feeling of voyeurism on him while the audience chatter and wait for the start. There is something amazingly powerful of watching as the audience slowly come to the realisation that a production has started without this being clear.

Scott-Rowley is able to contort his body and facial structure to create different characters and scenarios – you rarely find that you truly know who he is or what his natural form is as he so amazingly transforms. He creates characters we know or see in modern world, or frighteningly creates people we know we have been or will become. There’s a tongue and cheek to it at times, but it is subtly and easily transformed into serious commentary. Abstract, with little dialogue and heavily leaning of physical theatre, some makes you laugh and intends comedic effect, some is beautiful and a work of art in itself and some is grotesque and full of truth. There’s a fluidity and seemingly subtle transition to the different “scenes” (if you could call it that) and a return to different characters, adding to a sense of monotonous repetition of life but also hitting home humorous but entirely serious points of who we are in a world going up in smoke.

YOU ARE GOING TO DIE is a physical theatre masterpiece. It is entirely absorbing, entertaining, humorous but hitting really poignant spots in every audience member.

(4 / 5)

(4 / 5)

(3 / 5)

(3 / 5)

(4.5 / 5)

(4.5 / 5)