(4 / 5)

(4 / 5)

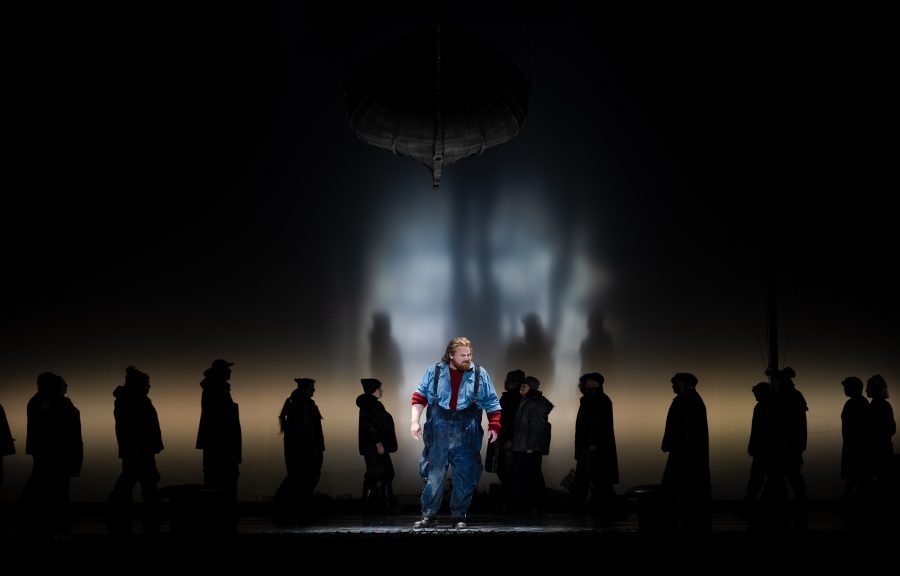

In these dark times of international upheaval and authoritarianism, this tale of suspicion and ostracism feels more potent than ever. Peter Grimes is a fisherman accused of the death of his apprentice. The death is ruled accidental, but in the minds of the people in the village, Grimes is guilty. The judgment is sealed once his second apprentice also falls to his death.

Peter Grimes is made an outcast, yet he is firmly rooted in his village. The Suffolk coas is much more than a setting; it plays a part in the unfolding of the drama. The music captures the sea and in particular the storm with rising trombones and trumpets and the winds conveyed by the strings. The storm is physical and metaphorical of the inner turmoil of Grimes. Grimes is tied to his village and that tie brings him to his demise.

The tragedy is interspersed with quasi-mystical moments, such as in the aria “Now the great Bear and the Pleiades”. This is performed impeccably by Nicky Spence as Peter Grimes. Spence has a beautiful timbre and conveys the ambiguity of the character with great effect. Less convincing is Sally Matthews as Ellen, Grimes’ lover, whose singing is a little too structured. She brings a coloratura that sits uneasy in Britten’s austere music.

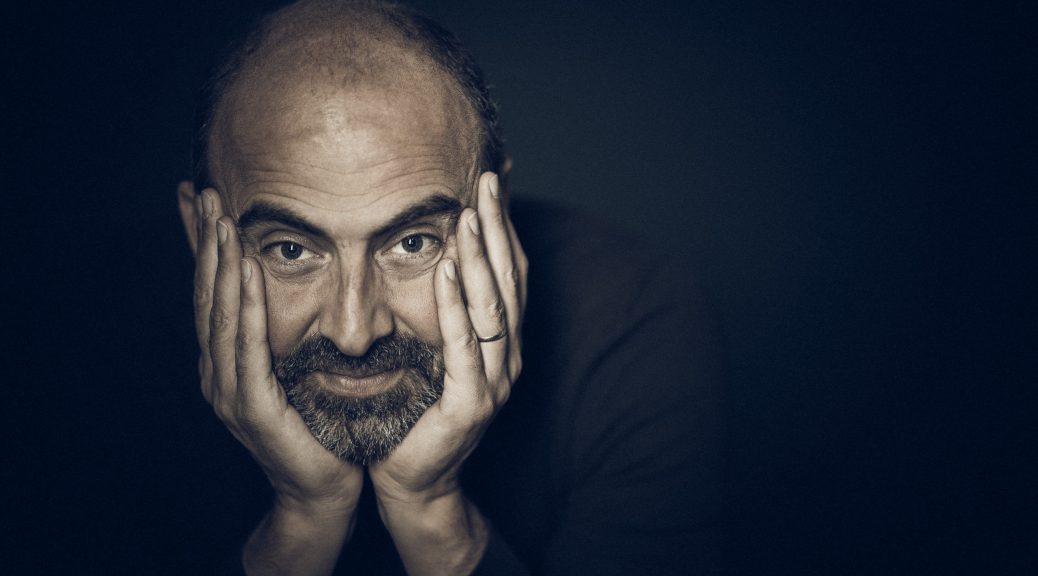

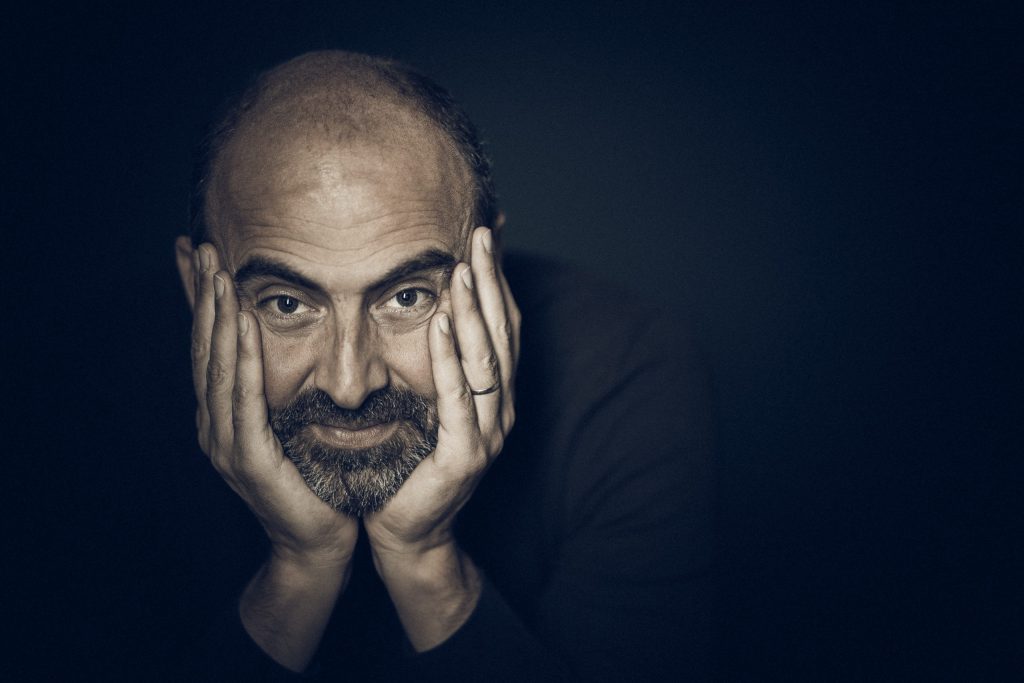

Strong performances come from David Kempster as Captain Balstrode, Sarah Connolly as Auntie, and Catherine Wyn-Rogers as Mrs Sedley. Tomáš Hanus is back conducting a powerful orchestra, albeit slightly uneven. The ensemble moment are indeed impressive and the WNO chorus is at its best. They embody the people’s unified condemnation of Peter Grimes.

Britten’s social realism is evident in the costumes recreating a working class 1980s village. The stripped down production brings to the fore the sense of oppression, anger, and defeat. The opera suits the minimalistic style, yet it feels like such minimalism has been forced on the WNO by recent funding cuts. The direction and staging are effective, the performances strong, and more funding well deserved.

(3 / 5)

(3 / 5)