(5 / 5)

(5 / 5)

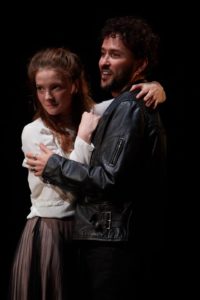

OMG Legally Blonde is back in town! Anthony Williams UK revival of the musical adaptation of the hit 2001 film, which starred Reese Witherspoon in the iconic role of Elle Woods, is back in a dazzling pink-hue production of frothy songs, fabulous sets and catchy dance routines. With more sparkle than one will find on Strictly Come Dancing, Legally Blonde The Musical, will brighten up the coldest and darkest of winter nights.

Based on the hit film it follows the perils of Elle Woods played by home-grown talent Lucie Jones, a cheer-leading sorority girl who ditches her air-head image to train as a lawyer at the prestigious Harvard School of Law in the hopes of winning back her preppy boyfriend, Warner Huntingdon III, played by Liam Doyle. Packing up her trusty pooch, Bruiser, and with the support of a new bunch of friends she quickly learns that one can be an intellect, have a heart, superior fashion sense all whilst battling against envy, pettiness and a sordid professor.

Lucie Jones is a perfect fit for the role, her beautiful voice and her ability to do the bend and snap to perfection brings the perky Elle Woods to life in all her pink glory. Whereas Liam Doyle who plays Warner Huntingdon III exceptionally well especially when singing Serious, where Elle is expecting to him to propose but ends up breaking up with her. However, Rita Simmonds (most well-know for playing Roxy Mitchell in EastEnders) is a true revelation with her beautiful singing and great characterisation of salon owner Paulette Bonafonté. Her ode to her character homeland with the song Ireland saw Simmonds balance comedy with genuine emotion perfectly all whilst doing a fabulous river dance. As for Bill Ward’s interpretation of the disgustingly slick Professor Callahan, he commends the stage with his presence and gets all the Panto boos, the highest accolade for any antagonist. It’s safe to say that the biggest cheers of the night and who drew the biggest smiles from the audience was the four legged cast comprising of Bruiser played by Bruisey Williams-Dood and Rufus played by a local star canine.

Legally Blonde The Musical is fun and fluffy, lifting the darkest of spirits and bringing them into Elle Woods’s fabulous bubble-gum pink world. It is light-hearted and delivers its fair share of touching moments all set against a backdrop of glitz, glamour and girl power.

Tour dates and ticket information can be found on Legally Blonde The Musical website.

Tag Archives: Review

Review Justice League by Jonathan Evans

(2 / 5)

(2 / 5)

And so, seeing the unquestionable success that MARVEL has been having with their shared cinematic universe DC have stumbled greatly to get to this point. But nothing was gonna stop this cinematic train so, we just have to deal with it.

What brings our different heroes together are three boxes called “Mother Boxes” if all three are brought together they’ll destroy the world (basically). The one that is out to get all these Mother Boxes is a giant being named Steppenwolf (Ciaran Hinds), he’s about ten feet high, clad in Armour, wields a large axe and spouts over-the-top dialogue. His role is similar to Loki in Avengers (even to the point of wearing over extravagant headgear) but he lacks Hiddelston’s charisma as well as fails to convey a real threat. He’s just a big threat that is no more interesting or memorable that a generic video game boss.

The first members that have already been established are Batman (Ben Affleck) the dark brooder that is just a skilled human with great technical resources and detective skills. Wonder Woman (Gal Gadot), she was the best thing in Batman v Superman and her own movie was the best of these movies but also rather good. The same present here. The Flash, the speedster played by Ezra Miller. He is here to portray the every-man, being more trepidatious and a lot more dumbfounded when giant man and bug creatures appear. But he says some things that are just odd, it is a weird thing that writers do where they put in quirks and think they’ve made a character, they haven’t, he gets better as the movie goes on but when he starts he might be an alien on Earth. Next is Aquaman (Jason Mamoa), he can breathe underwater, is very strong and wields a large five pronged spear (not a trident), he will probably be the breakout character, being a swaggering brawler. Finally is Cyborg (Ray Fisher), originally a young student named Victor Stone has now been transformed by the Mother Box technology and is fused with it.

Probably the worst kept secret and obvious plot point that any five year old could see coming is that Superman (Henry Cavil) returns (he died in the last movie). He does and he is much better here than in the previous two movies, he knows what smiling is, I believe he’s an optimistic person and they gave colour back to his costume instead of a grey filter.

Due to a family tragedy Snyder had to pull out of the movie. Most of it was completed but still needed finishing. Director Joss Whedon stepped in and completed the project. There is only so much one can really affect a movie when probably over seventy five percent of it has been completed. Whether it be due to fan outcry or Whedon inserting it in where he could there are much more smiles in this movie. Characters are smiling and aren’t brooding constantly. Having one moody one on a team is fine (that’s what Batman’s there for) but the others need to bring a balance of different types of characteristics.

Also more present in the movie is colour. They still use heavy amounts of black but they are contrasted with deeper, vivid colours of red, golds etc. This is a better direction to go, it keeps the colour but visually distinguishes it from the MARVEL movies.

Probably the biggest failure of the movie is the score by Danny Elfman. Not at any point did I feel my spirits roused by the music and I cannot hum any of the score. It is unfortunately forgettable and not moving.

Unlike all the other movies this one does have a post credits scene. So if you are so inclined stick around and you wont just see the credits scroll by.

So it has indeed been a very bumpy ride. It did not get off to a good start at all and from there on it got worse. But now the pieces have come together and the final result probably wasn’t worth it but it also wasn’t a complete disaster. It was actually rather serviceable.

Jonathan Evans

Review Professor Marston & The Wonder Women by Jonathan Evans

(4 / 5)

(4 / 5)

She is one of the most iconic female characters in pop culture. She is instantly recognisable and you most likely know her name. She stands for truth. But in creating her secrets had to be kept to preserve love.

Earlier this year the mass audience were introduced to Wonder Woman through her first film. Now she is more popular than ever, this is the perfect time to tell this fascinating story of the deep psychological ideas that went into her creation and first few stories as well as the just as interesting behind the scenes situation of the people that inspired her.

The man who co-created her was man named William Moulton Marston (Luke Evans), a university professor who teaches psychology. He would go on to invent the lie detector machine. While there with his wife one of his students catches his eye. His classes teach about the mindset of giving yourself up to an authority figure in a relationship.

Elizabeth (Rebecca Hall) is his official wife whom he has known since childhood, she has dark hair and is more than qualified to be a lecturer at any University, but because she is a woman she cannot gain any diploma. Her and Marston enjoy heated debates. Olive (Bella Heathcote) is blonde, a few years younger and even though she is descended from two of the most outspoken and radical feminist of her time was raised by nuns so is timid and tacked but still very intelligent.

He loves his wife, however he also loves Olive and they love him as well as each-other. What are they to do? The love is real but the society in-which they live will never accept them, is it even worth trying?

Luke Evans himself is a gay man and the writer/director Angela Robinson is a lesbian. They are both open about their sexuality but the world still does not fully embrace people of non hetero sexuality so they are probably the perfect people to tackle this material.

Adding to the revealing nature of the movie is the layering of the actual Wonder Woman comics that were written by Marston and indeed do feature Wonder Woman herself and other women caged, tied-up, spanked etc. The fact that they were able to get approval for the actual material shows and bravery and how unashamed on behalf of DC Comics. This is the story and ideas that went into the character and are addressing it.

The theory of loving submission isn’t just all about getting tied-up and/or spanked (though the physical acts are a part of it) it is about letting go of control, it has been said that you cannot love someone and control them, the acts allow the others to be the master to ones who would otherwise not be.

Being that this takes a look behind the public perception of a famous character and shows the story of the real people behind the scenes one will probably be reminded of Hollywoodland (an equally good movie).

This movie tells the story of love that is still rather unconventional now and seemingly impossible at the time it happened. There are details about the production of the character of Wonder Woman that are skimmed over as well as a few other moments that take a leap in time in order to fit the correct running time. But the story it tells is one of love and understanding and it effectively conveys that message.

Jonathan Evans

A BSL Captioned video review of Contractions by Deafinitely Theatre, review by Stephanie Back.

A BSL Captioned video review of Contractions by Deafinitely Theatre. Reviewed by Stephanie Back.

Review Wait Until Dark, New Theatre, Cardiff by Jane Bissett

(4 / 5)

(4 / 5)

As I made my way to the Theatre on a dark and wet November evening I was unaware of the theatrical experience that is Wait Untill Dark would have on my walk home – in darkness…..

WAIT UNTIL DARK is a cautionary tale set in the mid 1960s. About a young photographer (Sam) who in agreeing to assist a fellow passenger on an aircarft flight from Amsterdam sets in motion a chain of events that will affect his household in a way he could not fore tell nor indeed understand.

Human beings are either able to embrace darkness or have an inate fear of it. There is something about the isolation of being in the dark which enduces our inner fears of the things we cannot see or understand.

This story centres on Susy the newly married wife of Sam. Susy is blind and learning to live her life in darkness following an accident.

As the story unfolds we watch as a small gang of vilains are trying to discover the whereabouts of a missing doll which has been used as a carrier for drugs.

The gang mistakenly believable Susy knows the whereabouts of the doll although is unaware of its value. They set in motion an elaborate plan to retrieve the doll by deception and fear.

Using a tried and tested method of operation the gang gain access to the basement flat and conduct their search with the assistance of Susy who now believes her husband is in danger and if the doll is discovered in his possession he maybe under suspicion of a murder of the woman who originally asked him to take care of the doll.

Despite her blindness Susy soon becomes aware of what is happening as she hears and senses the strange behaviour of the men and is suspicious of their real motives.

With the assistance of her neighbours daughter she sets out to change the power balance to her advantage and to keep herself alive until her husband can get home.

Although set in the 1960s this story could have taken place at any time and in any context and is the stuff that good thrillers are made of.

All the action takes place in a basement flat and the set design was true to the time period in which it was set. A mention must be made of the use of the stair case and we can only commend the cast on their fitness levels as they negotiated the stairs all evening.

Katrina Jones portrayal of Susy was outstanding, a smart woman, in love with her husband and astutely aware of her surroundings. Indeed it was only at the curtain call that it entered my mind that Jones was actually blind.

Shannon Rewcroft gave an amazing performance as Gloria (age 12), so much so that it became believable that she was 12.

The gentlemen of the cast brought the play to life and Tim Treloar’s performance as the gang mastermind ‘Roat’ sent a shiver up the spine.

The whole atmosphere of the play hinged on the set design, lighting and sound and to this end I must commend David Woodhead, Chris Withers and Giles Thomas for bringing to the stage the visual and audio experience that left us all wanting more.

During the final act, as the story reached it climax, the effects on stage not only heightened the scenses of the audience but pulled them further into the action that was taking place in front of their eyes and the tension was almost tangible.

Playwright Frederick Knott’s (1916-2002) legacy to the theatre was believable drama where he set the scene and delivered a thriller that has stood the test of time.

Director Alistair Whatley gave us an evening of sheer pleasure and this amazing cast brought the play to life to create an unforgettable evening of thrilling theatre at its best.

WAIT UNTIL DARK plays at Cardiff’s New Theatre from;

Tuesday 14 – Saturday 18 November at 7.30pm

On Wednesday, Thursday and Saturday there are performances at 2.30pm.

For further details about the show or to book tickets call the Box Office on 02920878889.

Review Fiction, Bikeshed Theatre by Hannah Goslin

(4 / 5)

(4 / 5)

In the brick theatre of the Bikeshed, we are separated into singular seating, correspondent to our numbered headphones. Instantly we are dubious of what is about to happen especially when you end up in the front row and your guest is right at the back.

The only other things in the room apart from us spaced out is a large projection screen and a lectern. The projection screen acts as our welcome party before we are delved into sheer darkness.

Fiction sees us travel through a world of imagination and suggestion. Being in pure darkness, we feel vulnerable and open to the elements. Therefore sounds effect us more than normal, we do not feel as safe as we normally would and suddenly there are voices describing and taking you through an almost apocalyptic world and story.

One hour of this would, from the outside, seem tiresome but somehow the content of the narrative and what we create in our mind keeps the entire experience interesting and new.

The wonderful thing about this event is that while the narrative is the same, our own minds create a world that would be different to the next person. An uncertainty of whether the person speaking is sat next to you or not – yet you still do not reach out and move despite a 95% assurance it’s all coming from the headphones.

Fiction is very clever, intense and very simple, yet brilliantly executed. Such a clever experience is very unique and totally worth undertaking.

Hannah Goslin

Review The Cherry Orchard, Sherman Theatre by Barbara Hughes-Moore

The third part in the holy trinity of dynamic duo Rachel O’Riordan & Gary Owen’s co-productions, and the jewel in their collaborative crown, is their adaptation of Anton Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard, seamlessly updated from pre-Revolution Russia to Thatcherian Pembrokeshire.

Centring on a family of wealthy landowners just as their luck and lucre begin to dwindle, the updated Cherry Orchard follows the return of boozy, bombastic matriarch Rainey to her childhood home mere days before it’s to be sold at auction. Her reappearance heralds an era of chaos, confusion and uncertainty, not just in her personal relationships but in creating a complex and combustible legal situation that threatens the stability of her nearest and dearest. Over all hangs the spectre of Mrs Thatcher, promising the working-class freedom with one hand, and mass unemployment with the other.

Rachel O’Riordan deftly directs the excellent ensemble, expertly exhuming the characters’ inner demons in a way that is interesting and realistic, but not clumsy or banal – a tricky line to navigate. Gary Owen adds heart and humour in his adaptation of Chekhov’s play; Owen’s version is not just more accessible than its source, but often improves on the original through its use of language, and its inclusion of Gothic undertones (spectral trains and ghostly children appear infrequently). O’Riordan and Owen work in tandem to ensure that we not only know these characters as well as our own families by the close of play, but that there are still myriad mysteries to uncover about the complex cast left after the curtain (metaphorically) falls.

The cast itself capably carries a modern audience through the dual layers of antiquity: first, to the 1980s, which have evolved into a sort of nostalgic Eden in pop culture thanks to the influence of Stranger Things, Stephen King’s It, and Guardians of the Galaxy to name but a few; and secondly, to the chequered past of Chekhov’s turn of the (20th) century Russia.

The linchpin of the piece is Denise Black’s winning, wine-soaked wonder Rainey, sauntering through life with a perpetual cigarette/ alcohol combination in hand. Her brash bravado and devil-may-care allure masterfully conceals the pain of her young son’s death, and the guilt she feels at her (careless, not calculated) part in his passing. A role that could easily slide into caricature is rendered relatable, realistic, and raw courtesy of Black’s amazing acting.

Matthew Bulgo excels as Lewis, a relatable downtrodden everyman who slowly sheds his skin to reveal a treacherous snake beneath. His cheerful ordinariness in the first act becomes tainted by the insidiousness of his ultimate decision, and the moment in which he strides around Rainey’s house proclaiming ‘these are my floors’ is particularly haunting.

A star-making turn by Alexandria Riley as Dottie gives the production a bold, beating heart. She is snarky, sarcastic, self-assured and frequently takes her wealthy employers down a peg with her biting insight about their whiny, work-shy ways. Although Riley injects a grounded grumpiness to the family’s affluent antics, she revels in revealing the hidden, hurt soul behind the bolshy brashness. Her relationship with Rainey is truly touching, and anchors the action with emotion – more than Rainey ever shows her other daughters.

Speaking of which, Hedydd Dylan and Morfydd Clark cleverly act as clear counterparts to one another – Dylan is Valerie, treading a delicate line as the exasperated, underrated eldest (adopted) daughter of Rainey. Although she often seems the coldest and most clinical of the bunch, chinks in her armour gradually appear, revealing a deep need to be loved by Rainey that the object of her desire – tragically – cannot fulfil. Clark is Anya, Rainey’s youngest (and only) biological daughter. Anya is the complete opposite of the uptight Valerie – free-spirited, defiant and romantically adventurous (whereas Valerie pins her romantic future on a friend of the family who’s been there all her life). Clark does a lot of heavy lifting with lyrical ease; as her character has the most monologues, she often has to wax poetic about the heady nostalgia of the past – she is the chronicler of the piece, the notary of nostalgia who ensures no-one forgets how precious the eponymous orchard is to the family: as a symbol, a cipher, and, ultimately, a swan song.

Richard Mylan plays Ceri, Anya’s former A-Level tutor with whom she reunites and (impulsively) romances, despite the fact that Anya has a stable, loving (and ostensibly rich) girlfriend back in Uni. Mylan plays Ceri with a potent combination of socialist vigour and musical snobbery that would make millennial hipsters blush. He probably has ‘Disaffected Youth’ tattooed in his soul, and he’s clearly relishing every second of acting like Sid Vicious and Michael Sheen’s lovechild. From the second he struts onto the stage clad in black from his boots to his leather-jacket and era-appropriate mop-top, you know exactly the kind of guy he is. Except you don’t, because halfway through the play, after denouncing once-beloved bands for signing to a label and selling out to ‘The Man’™, he abruptly announces his long-held desire to start his own record label, cheerfully (and obliviously) selling out in the exactly the way he just condemned.

My only disappointment in the adaptation of characters was that of Gabriel. Despite being thoughtfully and subtly portrayed by Simon Armstrong, his translation from Chekhov to this play was the only one which fell flat for me. In both he represents the laziness of the wealthy who don’t need to work to live – and Gabriel’s news of a (potentially fraudulent) career choice is poorly received by his relatives, and his failure seems inevitable However, the tragedy of Chekhov’s Gabriel was that he spoke a lot of sense, despite the fact that his relatives often shushed him mid-maxim. They find him annoying, we find him insightful. In this adaptation, Gabriel is demoted to doddery window dressing, and denied the musings his original counterpart was given in spades.

I had the pleasure of being on the post-show discussion panel on 24th October; led by Timothy Howe, the Sherman Theatre’s resident Communities and Engagement Coordinator, the panel consisted of Gary Owen himself, Dr Tristan Hughes (a senior lecturer in Literature at Cardiff University), and myself. I was there to represent Law and Literature, a field of study which boasts two complementary strands of thought: firstly, Law in Literature, which looks at how law is portrayed in literary texts; and secondly Law as Literature, in which legal texts are analysed using literary tools of interpretation. The Law and Literature module at Cardiff School of Law and Politics, led by Professors John Harrington and Ambreena Manji, have been linked up with the Sherman Theatre since 2016, incorporating their productions of Love Lies and Taxidermy, and now the Cherry Orchard, into the module over the last two years, offering a fantastic opportunity for students to not only study the texts, but see them performed live – and starting off discussions as to the parallels between performing law and performing theatre.

The post-show panel discussion was a hoot! Gothic sensibilities were touched on, Chekhov’s ghost was invoked, and new terms were coined – ‘melancomedy’, i.e. melancholy comedy, rather than a comedy about melons. One of the topics discussed was the evocative use of sound and imagery in the play; for me, the most striking image was the doorway from the house – dual monoliths illuminated from within by an afterlife-inspired white light. It was as if the living room from Roseanne led out into the stairway to heaven in A Matter of Life and Death. Juxtaposing the homely with the heavenly was an inspired piece of stage production, and gave the play an almost supernatural quality that was only enhanced by the occasional appearance of the spiritual presences mentioned above. Tristan and I exchanged Gothic interpretations of the play, and he felt that the most striking moment of the play was the haunting sound of the siren that heralded war with Argentina. A similarly chilling noise was the sound of the cherry orchard being chopped down offstage, the axe cutting into wood with a visceral thud akin to the sound of breaking bones and severed flesh, as if being murdered – very Gothic indeed.

Looking at the play using the lens of Law and Literature allows the legal aspects to shine under literary interpretation and vice versa. It was fascinating to watch how the play represents lots of different aspects of law: land law, family law (particularly adoption law), and contracts. I can assure you from experience that land law is one of the driest, dullest and yet most important and practical facets of the entire legal system. Memories of studying it at undergrad bring flashbacks of long, lethargic legal spiel, volumes upon volumes; it certainly felt like I was reading them in perpetuity. But the Cherry Orchard, in bringing complex legal issues like land law into the context of characters you care for and empathise with, was a paragon of Law in Literature – it represented the legal (and political) issues of the day, making them relatable and understandable, as well as informing us of the legal consequences through characters whose futures we grew to worry about.

There were doubles a go-go in this show (of particular interest to my Doppelganger-centric PhD). For a start, Dottie, Ceri and Lewis acted as the lower-class literary foils to the upper-class Rainey and co. Whereas Rainey and Anya want to keep the orchard for themselves, Lewis plots to buy the land and transform it into council houses thanks to Maggie Thatcher’s new scheme. Rainey and Anya want to linger in the home of their charmed childhoods, Dottie thinks they just don’t want lower-class people like her living next door; the response couldn’t be more insulting when Rainey effectively claims Dottie’s ‘one of the good ones’, a racist, classist sentiment that Dottie rightfully rails against. It only reinforces the fact that Dottie was spot on about their reasoning. Whereas Dottie works within the system to provide for herself and her family, Ceri fights against it, proclaiming the power of the proletariat – whilst dating a rich girl. I mean, the two aren’t mutually exclusive, but it does somewhat foreshadow his forsaking his principles later on, just as he thinks going late to the dole office is a middle finger to authority. Gabriel is the most passive character of the play, and has no active involvement in the action – well-meaning but weightless. Not to mention the obvious doubles running through the play – ‘I’m a ghost. I’m not here’, Rainey whispers, feeling that she died in spirit when her son did’. The ghostly segments often feel like an afterthought, and I would have liked to explore them more – though, as they are now, they act as spectres of the past, relics and afterthoughts – and as such, they’re in good company with Rainey and her ghosts of love and luxury.

I can’t rave about this show enough. It is a triumph for those involved in making it, and a treat for those lucky enough to see it.

Barbara Hughes-Moore

Review The Cherry Orchard, Sherman Theatre by Corrine Cox

(5 / 5)

(5 / 5)

Gary Owen and Rachel O’Riordan’s radical reimagining of Chekhov’s classic masterfully transports the narrative of The Cherry Orchard from pre-revolutionary Russia to early 1980’s Britain at the outset of the Thatcher regime. The parallels of the two landscapes, both on the cusp of societal upheaval, provides an apt setting for Owen’s exploration of class equalities, guilt and grief.

At the beginning of the play we meet Rainey, returning to the family home in West Wales and the memories of the son that continue to haunt her. With no money left and the future of their home increasingly uncertain, could an agreement with former tenant Lewis save the property from impending auction?

The one set staging creates an intimacy and surprising relatability between the family and the audience which transcends class preconceptions through the sense of a shared space which we co-inhabit over the course of the 3 hours. The clever use of space enables us to effortlessly join Anya in the Orchard, envisage the view down to the shore and experience the poignancy of Rainey and Dottie’s moment in the grounds. The presence of Josef is hauntingly conjured throughout.

Whilst Richard Mylan and Alexandria Riley provide us with a great deal of the humour throughout, it is Riley’s Dottie who most poignantly captures the extent of the injustices that class inequality can create; for in a society where time is money, who is afforded the luxury of the time to grieve? Juxtaposed with just how detrimental this ‘indulgence’ has rendered Rainey – a decade of alcoholism and guilt – we are left to un-judgingly straddle the vast void between the extremities of each’s experience.

A powerful, thought-provoking piece and one not to be missed.

Cast

Simon Armstrong

Denise Black

Matthew Bulgo

Morfydd Clark

Hedydd Dylan

Richard Mylan

Alexandria Riley

Creative

By Anton Chekhov

A re-imagining by Gary Owen

Director Rachel O’Riordan

Designer Kenny Miller

Lighting Designer Kevin Treacy

Composer and Sound Designer Simon Slater

Casting Director Kay Magson CDG

Get the Chance member Corrine Cox.

Review The Cherry Orchard, Sherman Theatre by Kevin Johnson

This is not a new version of the Chekhov classic, but a ‘re-imagining’ by Welsh writer Gary Owen, of Killology & Iphigenia In Splott fame. Owen relocates it from 1890’s Russia to the Pembroke coast in 1982, just prior to the Falklands War, which makes for a very interesting choice.

It feels like every dysfunctional family drama you’ve ever seen, until you realise Chekhov originated the idea of real characters, with real problems, talking like real people.

Family matriarch Rainey, who has crawled into a bottle after the death of her son over a decade ago, followed soon after by the suicide of her husband, is virtually dragged back to the family home from London by Anya, her youngest daughter. Her self-destructive lifestyle has lead to the family home on the Pembroke coast being auctioned off to pay the debts.

Val, her eldest daughter, has held things together, but they need Raynie’s permission (and signature) to save it. All agree that the only viable option is to sell off the ancestral cherry orchard for redevelopment, but will she see it that way?

This play is incredibly funny and well-worth seeing, if only for the way Owen makes it so accessible to Welsh eyes. The ‘Russian peasants’ now come from housing estates, the decaying aristocracy are English interlopers, and the Communist revolutionaries are now Thatcherites, sweeping the past away without a thought or concern.

At the heart of the play is the idea that the future is farther away than we hope, while the past is always closer than we’d like. The characters here are continually haunted, not by spirits, but by the ghosts of memories, taunting them with remembrance.

Rainey tries to forget through excess, her guilt at losing her son gnawing away at her, like a rat sown inside her skin. In the end it causes her to take drastic action, and Denise Black brings all this out in a masterful performance that makes you feel sorry for her, even while she’s being a monster to all and sundry.

The entire cast take their moments when offered, yet still make this a true ensemble piece. Morfydd Clark is sweetly sensual as the young Anya, while Hedydd Dylan as her elder sister Val, shows us a woman who tries to run other people’s lives, but fails at her own.

Simon Armstrong as Gabe, Rainey’s brother, is amusingly ineffectual, yet quietly sharp. When Val talks about Rainey not telling him about her plans to leave he replies “We’ve been brother & sister half a century. Through awful things. Do you think saying ‘goodbye’ makes any difference?”

Alexandria Riley gives us a Dottie that is down to earth yet shows the love/hate relationship she has with the family, while Richard Mylan is funny, while also imparting a wise naïveté to Ceri.

Mathew Bulgo, given the task of Lewis, the ‘poor boy made good’, effects a performance of subtlety that defies the historical villain the role has been seen as. With the insults he endures from the others, and denied the role of ‘family saviour’ by Rainey, it’s hard not to feel sympathy for him.

Writer Gary Owen conveys a situation full of layers, and also offers some nice ironies. Ceri’s expectations of Margaret Thatcher getting the blame for the Falklands War being one, Gabe’s job offer as an investment banker another.

When you add all this to Rachel O’Riordan’s deft direction, Kenny Miller’s intriguingly skewed set, and Kevin Tracey’s ingenious lighting, the Sherman Theatre demonstrates yet again that it is punching well above its weight in the theatre world.

There is so much going on here that I actually re-read the script in one go afterwards, and was still as gripped as I was by seeing it. The play is funny, ironic, witty, sarcastic and quietly heartbreaking. It is a story of loss, of people, places and things, and how memories both haunt and define us.

As F. Scott Fitzgerald once observed: ‘We beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past‘.

http://www.shermantheatre.co.uk/performance/theatre/the-cherry-orchard/

Kevin Johnson

Review Of Mice and Men, August 012 by Troy Lenny

All photographs credit Studio Canno

(4 / 5)

(4 / 5)

Of Mice and Men is a story of loneliness and misunderstandings. I remember studying this literary art in high school, but I didn’t notice the finer details, only the outline.

On Wednesday I watched Of Mice and Men presented by August 012, at Chapter ArtCentre. The outline of the story is two friends, George Milton and Lennie Small who are two workers in the Great Depression. To escape their cruel reality they share a distant dream that persuades them they will own their and land, “an’ live of the fat of the land.” This dream swirls colours of great happiness into their lives.

I do not want to cut curiosity out of the plot, so I will express little of this element. There are two stern problems blocking their dream. Lenny has an intellectual disability, and naively often strokes problems at work. And George and Lennie need ‘stake’ (money) from work so they can whirl their dream into reality.

I rate this production four stars. Why? Because the production was extraordinary. It had a partial modern theme which drew out the connection that many of the problems in Of Mice and Men still exist today, if you thin your eyes. Additionally, the production style conflates imagination with reality through dreamy description and because the audience’s seats are placed on an empty stage an immersive reality surrounds you (plus you may be able to play cards with the characters!)

I would recommend anyone reading this to book a ticket, and visit the world Of Mice and Men because its performance style will enlighten tenebrous learnings. One element of the production I noticed during this production was all of the characters were Greatly Depressed, but they wiped their tears and some tried to smile and others frowned. For example: Callous Curley, always had a curled fist most likely because he felt lonely, but due to his expected masculine role he couldn’t express his feminine emotions so he was always steaming frustration. Consequently, Curley’s wife felt lonely, and wandered looking for company and due to expected feminine roles she likely thought the only way to attract a man’s attention was by swirling hips.

I would like to thank all involved in the production Of Mice and Men for their creative minds, and extraordinary performance style – it was striking.

Troy Lenny