We asked our team to choose their three cultural highlights of the year, along with a favourite event and/or organisation. Enjoy reading their individual responses below.

Young Critic, Gareth Williams

Junkyard: A New Musical (Theatr Clwyd, Mold) Real, raw, inventive, inspiring; provoking and entertaining social commentary; one of the most original pieces of theatre I think I’ve come across this year, with an exceptional cast, script, and set design.

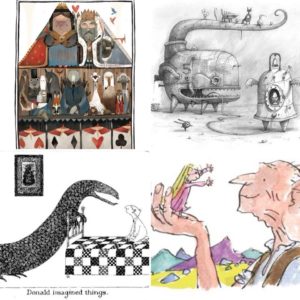

Alice in Wonderland (Storyhouse, Chester)

A truly charming and inventive take on this well-known tale; a talented cast who brought the characters of Lewis Carroll’s beloved children’s classic to life in vivid detail; perfect family viewing; the standout show of Storyhouse’s opening season.

Broken (BBC Drama Series)

Sean Bean was excellent as the passionate yet broken priest trying to make a difference in a Northern working-class community; as always from writer Jimmy McGovern, a piece which dealt with contemporary social issues in an engaging, challenging and no-nonsense way; a beautiful portrait of contemporary Christian faith.

The opening of Storyhouse in Chester

A wonderful addition to the North Wales/North West England arts scene. A stunning building with a beautiful theatre, modern cinema, integrated library, and plenty of communal spaces. An arts space that is truly for the community, that is already making a positive impact on the city and its people through various projects, shows and initiatives.

Community Critic Kevin Johnson

Hamlet. Andrew Scott gave what I can only described as an Irish Hamlet, sad, bittersweet and quietly morose. He sees the humour through the madness and the sorrow, yet his heartbreak was always just behind his eyes. Like some romantic hero of legend, dark and brooding, he used this masterfully to make us care for the Dane all the more.

The setting was modern, innovative and intriguing. The play began with coverage of the funeral straight from a Danish cable news channel. The play within the play took centre stage, the cast sitting in the front row among us, their faces thrown by video onto screens around the auditorium. A clever use of old and new. They wore tuxedos as if at the opera, and were covered by cameras as such.

In other modern twists Polonius had dementia, Rosencranz and Guilderstern were a couple, and both Hamlet and his mother spoke with Irish accents, unlike Claudius. A superb and thoughtful production that gave me new insight into the play.

My second choice is Angels In America, the first London revival since the original in 1992. With Andrew Garfield taking the lead of Prior Walter, this was a huge play, both in ambition, talent and scope. Performed in two parts, it’s just over eight hours in total, but amazingly the time went by so fast.

Garfield won the Evening Standard Award for Best Actor but Nathan Lane is equally as good as the venal Roy Cohn, hurling racist insults from his sick bed at his nurse, and threatening his doctors with lawsuits, it was still hard not to be moved as he fought for his life using every dirty trick in the book.

Although I thought it slightly bloated, and perhaps too self-indulgent in places, the sheer audacity of the play steamrollers over such quibbles. This was a tour de force if ever there was one.

My third production is The Cherry Orchard, a homegrown reworking of Chekhov set in Pembroke in 1982. It made me so proud to see such a great play from a Welsh company, easily the equal of anything I’ve seen in the West End.

I’ve been a fan of writer Gary Owen since seeing Iphigenia In Splott, and Killology, also Sherman Theatre productions, and this was the ‘cherry’ on the cake, pun intended! The whole cast contributed to making it truly memorable, with Mathew Bulgo in particular creating a nuanced performance that defied good or bad and was just human.

Unsurprisingly then, my favourite company and venue of the year was the Sherman Theatre. As a theatregoer, I’ve been welcomed by every member of staff, it’s foyer is roomy and full of comfy chairs and sofas, and they continually produce work of the highest order, on both the small theatre and the large. Outstanding.

My cultural highlight of the year is a little unusual, given so many wonderful choices, but I’ve chosen Slava’s Snow Show. Premiering in 1992, it has toured all over the world, usually at Christmas. I’ve missed seeing it so many times, so when it played the Millennium Centre I was determined to catch it. And catch it I did.

Simply put, I was enchanted. When I tell you that I don’t like clowns, and that the entire cast are dressed as sad, world-weary clowns, you can see what an achievement this was!

There was no dialogue as such, no plot, and I can’t even begin to describe what went on, yet it evoked such joy and wonder in me that I remembered what it was like to be a child again. Suitable for ages 3-90, I’ve never seen anything that unites all the generations this way.

Created by Slava Polunin, a Russian clown and mime, its won several awards around the world, including the Drama Desk Award for Unique Theatrical Experience. I think that sums it up nicely.

Young Critic, Sebastian Calver

Oslo, National Theatre

The Grinning Man, Bristol Old Vic

Heinsberg, The Uncertainty Principle

3rd Act Critic, Helen Joy

This is difficult as this year, I was very selective and so was privileged to experience some truly brilliant performances. With one exception. My top top event, was the Hot Tub extravaganza and in part because of my involvement and also because it was so outside my ken. Talking about our engagement with the arts here in Wales and as inconvenient wimmin of a certain age, was most refreshing!

Shadow Aspect, Ballet Cymru. Casting light into dark places.

Le Vin Herbe. WNO Perfect. Simply perfect.

My venue of 2017 would have to be Blackwood Miners Institute. Welcoming, warm, good facilities, parking and a very personable attitude.

My Company of 2017 is Black Rat Productions. For making us laugh. Never underestimate the power of a well produced comedy. One Man Two Guvnors. Good hearty stuff!

Community Critic, Steph Back

You’ve Got Dragons, Taking Flight.

Slava’s Snow Show

Fear, Mr and Mrs Clark.

Young Critic, James Briggs

La Cage Aux Folles, New Theatre Cardiff. Such an emotive and fun musical in which the story is still very prominent today.

Anton and Erin Swing Time– A much needed touch of class from years gone by. Celebrating the best of dance and ballroom.

A Judgement in Stone– A classic murder mystery that left the audience on the edge of their seats. An amateur sleuths idea of heaven.

My Cultural event of 2017. Celebrating the New Year in London watching Cinderella the Pantomime at the London Palladium and watching the fireworks from along the river bank.

My company of 2017 is Cinderella at the London Palladium. A stellar cast that really did bring everything to the pantomime. With names including Paul O’Grady, Julian Clary, Lee Mead and many more it was ‘the’ theatre experience of 2017.

3rd Act Critic, Ann Davies

Swarm, Fio Productions

Rhondda Road, Avant Cymru and RCT Theatres

Art in the Attic

I would like to highlight the work of Rachel Pedley and Avant Cymru during 2017.

A venue of great importance to me during 2017 has been The Factory, Jenkin Street, Porth RCT.

Community Critic, Hannah Goslin

Running Wild, Theatre Royal Plymouth

The production took a book from the well known writer Michael Morpurgo (of War Horse fame) and just like War Horse, transformed the stage with great creativity to take us to different places, and make us believe that the animals were real on stage with intricate puppetry.

Flossy and Boo: The Alternativity, The Other Room, Cardiff

This show brings a different taste to the usual Christmas shows full of kids entertainment and religious entail. Flossy and Boo create and exciting, fun and fully adult show to get you in the Christmas spirit but laugh at it satirically. Full of unusual concepts, music and lots of comedy, The Alternativity really gets you in the mood for Christmas.

Fourteen Days, BalletBoyz, Exeter Northcott

An arrangement of dance pieces, all with different concepts, BalletBoyz manage to astound yet again with their seamless movement, great acting and wonderful stamina. Balletboyz seem to only get better and better.

My Company of 2017 must be BalletBoyz. They are just incredible!

3rd Act Critic, Roger Barrington

The Wind in the Willows, Sherman Theatre. Great fun, highly creative with a very talented production team.

The Cherry Orchard, Sherman Theatre.

Little Wolf, Lucid.

The best exhibition I have seen this year is : Swaps – David Hurn – An outstanding and important exhibition at the National Museum Wales .

Young Critic, Sian Thomas

Cardiff Fringe Theatre Festival, particularly the event in mid July (but all the events were stunning) where I read some of my own work. I met great people and had a wonderful time and it has definitely shaped my year. I’ve become more confident with sharing my own work and have enjoyed events later into the night too, which isn’t something I did enjoy before this festival.

Layton’s Mystery Journey. Even though I didn’t enjoy the game I think playing it and experiencing a franchise I’ve loved in the past in the present was important for me. It made me realise that things don’t always survive my rosé-tinted glasses of nostalgia, and upon taking them off I’ve grown a little as a person. I know my interests much better, I know what upsets me in media much better, and I know my inner circle of friends much better, based on how we all reacted. Sometime positive can come from something initially negative, and I’m glad something has.

Iain Thomas’ “300 Things I Hope”, something I read very early on in the year and something that has been the brightest spot of almost literal sunshine on my bookshelf ever since! It’s a book I’ve traded with friends so we can see which ones stick out to us, it’s a book that spurred me on in my own below-the-radar poetry endeavours, the book that hundreds of sticky notes stick out off, and it’s the book that I like to pull down every so often and flip to a page and remember exactly why I love it.

My company of 2017 would again be Cardiff Fringe. Discovered it this summer and have been attending the monthly fringe cafes in The Gate ever since! It’s been a great time and one I hope to carry on attending. I look forward to see where it goes in 2018!

My personal cultural highlight would probably be the day I finished the first draft of my book – August 12th, 2017! I’m making progress on my goals! I’m on a second draft right now, and could not be more thankful for this year. I’ve had a really great one!

Community Critic, Gemma Treharne Foose

Swarm, Fio Productions

The Mountaintop, Fio Productions

Sunny Afternoon, Wales Millennium Centre

The best company for me in 2017 is Fio for pushing the boundaries of theatre and creating thoughtful and impactful pieced by working with community groups. They also incorporate hard to reach voices in to their work.

The best venue for me in 2017 is Sherman Theatre for the work they do in supporting new voices in theatre, and the efforts they go to in order to make theatre an inclusive, accessible experience.

But I suppose two of my biggest personal highlights this year were finally getting to see the American Folk/Indie group Bon Iver. I’ve followed them for many years and never been able to get tickets for as they typically sell out instantly and cause websites to crash, etc. I once even considered flying to Hong Kong to see them on their Asian tour before realising that was a bonkers idea. My husband surprised me twice this year with tickets to see Bon Iver headline the Forbidden Fruit Festival in Dublin in June, then again in September at Blackpool Winter Gardens. My husband isn’t the biggest Justin Vernon/Bon Iver fan but it meant the absolute world to me. Through the concerts, I was also introduced to the work of Lisa Hannigan and The Staves, which I’ve really enjoyed since the Dublin concert. I wouldn’t say I am massively up to date, experimental or fashionable when it comes to music – I like what I like, but despite the horrendous rain and mud, these two concerts were so meaningful for me. I’ve promised my husband I won’t make him sit through any more whiny Justin Vernon music in 2018. But this of course now means I will be dragged to some kind of weird Cajun/Zydeko/Blues music fest. There’s always a trade-off!

Young Critic, Vicky Lord

Woman in Black. New Theatre, Cardiff. It was something truly different. Obviously it was still scary to the point of terrifying but there were just so many layers of meaning that were left unsaid so that the audience could figure them out it was just truly flawless.

Blood Brothers, New Theatre, Cardiff

Miss Saigon, Wales Millennium Centre

My favourite cultural moment was seeing Lenny’s disability named as Dyspraxia in the August 012, Chapter Arts Centre production of ‘Of Mice and Men.’

Best Organisation, Wales Millennium Centre. It provides a gorgeous temporary home for West End hits allowing people who can’t travel to London the chance to see them.

Community Critic, Emily Garside

La Cage Aux Folles, New Theatre

Rent, WMC

Where Do Little Birds Go, Cardiff Fringe

My company of 2017 is Taking Flight, particularly for their work with young people.

Young Critic Corrine Cox

The Cherry Orchard, Sherman Theatre

Sunny Afternoon, Wales Millennium Centre

In terms of inspirational organisations in 2017, I’d pick National Museum Wales for being genuinely collaborative and inclusive. I have loved their 2017 programming (especially Artes Mundi, Gillian Aires, Agatha Christie photos and Who Decides?) I am also following the exciting developments and vision for St Fagans.

Artes Mundi was personal cultural event of 2017. I found Lamia Joreige’s Beirut piece really interesting and loved Bedwyr Williams’ Big Cities – I think I went back to see the exhibition four times I enjoyed it so much!

Community Critic, Barbara Hughes Moore

The Cherry Orchard, Sherman Theatre. This was not only a pitch-perfect translation of the source material, but a highly relatable, funny and melancholy family drama.

Rip it Up, St Davids Hall. A sublime show, what it lacked in narrative it made up for in energy, fun, and spectacular dancing.

Burning Lantern, St Fagan’s. Despite Queue-Gate, the musical acts were stunning, sublime, and sung their hearts out.

I’d have to nominate Sherman Theatre for my venue of 2017. We on the Law and Literature module at Cardiff have been linked up with Sherman Theatre since 2016, and they have been nothing but supportive, encouraging and welcoming – we have even built in their plays, performances and most recently a post show discussion panel into our module – and I was honoured to be on the post show discussion panel for The Cherry Orchard. They have also kindly come in to speak to our students at lectures – most recently Tim Howe, Communities and Engagement coordinator, led a very successful session on Law, Theatre and Performance, and our Law and Lit students were highly interested and engaged.

My favourite cultural event of the year was Pride 2017/ Return of the Big Weekend. It was my first Pride and it was utterly joyous, especially (or perhaps deliberately & defiantly in spite of) all the dreadful things that happened earlier in the year & the year before. It was beautifully, joyously defiant.

Young Critic, Eloise Stingemore

Funny Girl, Wales Millennium Centre. Sheridan Smith was outstanding, any misconceptions I had about her being the right person for the role where blown out of the water the minute she belted out the first song of the show.

Grease, Wales Millennium Centre. A show that I never wanted to end, a truly spectacular musical in every sense of the word, I want to hand jive baby for days after.

Dinosaur Babies, National Museum of Wales. A truly amazing exhibition for all ages and is worthy of going on tour all across the country with ‘made in wales’ (and with a little bit of help from America) being proudly stamped on it.

My personal cultural of event 2017 was the way the whole of Wales not just the Capital got behind our boys in wishing and dreaming them in qualifying for the World Cup. It seemed that the papers and even just people on the streets whether the be commuting to and from work or having a drink in the pub where talking about it and with so much pride that it made my proud to be Welsh.

Community Critic, Patrick Downes

The Addams Family Musical at Wales Millennium Centre

For a musical to have such an effect on me after hearing the songs for one time, it’s something a little special Creep, cooky, and altogether brilliant all round performance

Harry Potter and the Cursed Child Part 1 & 2 – Much anticipated, did not let me down!

Coldplay at Principality Stadium – Fourth time seeing the band, first time on home soil – Just stunning, even thinking about the night sends goosebumps up my arm

Cultural event; Tiger Bay The Musical, Wales Millennium Centre

Best Venue – Wales Millennium Centre – With a mix of populist, and culture for all ages.

(4 / 5)

(4 / 5)

(5 / 5)

(5 / 5)