Hi Emily great to meet you, can you give our readers some background information on yourself please?

I grew up in Powys in the countryside on the outskirts of various small villages and towns (we moved a lot) although my mum now lives in Carmarthenshire in the countryside. I started off wanting to be an actress and moved to London and trained at RADA when I was in my early twenties. I acted professionally for some years, mostly in theatre and ran a theatre company with some friends for a while that did fringe shows in pub theatres in London and then I got to my mid-thirties and decided I needed to do something different so I went to University in York and did an MA in theatre writing, directing and performance. When I decided to become a mature student I didn’t really have a new career in mind, I just wanted a degree because when I was at RADA you didn’t get one. I was never particularly studious in High School (although I was always good at English and Drama) and I hadn’t written an essay since GCSE’s so I was amazed and thrilled to discover I was really good at it and that I really loved the playwriting part of the course especially. I left with a distinction and hangover and haven’t stopped writing since.

So what got you interested in the arts?

My parents split up when I was two years old and my dad went back to London where he was from and my mum and I went to live in Wales. My dad came from a working class background where no one in his family were interested in the arts but somehow he developed a love of the theatre and used to go to loads of plays and get the cheap seats way up in the gods and he also loves books and films and art, and passed all that on to me. When I was three he got us cheap seats to see Peter Pan at the National Theatre and I was totally enthralled by it and apparently when we left the theatre I said ‘that’s what I want to do dad.’ So from then on whenever I went to visit him in London he would take me to the theatre, he’d take me to see Shakespeare, Chekhov, Tom Stoppard, Samuel Beckett and I just loved it, not that I totally understood everything that was going on but there was something magical about it all the same.

My mum encouraged me to join Mid Powys Youth Theatre and Powys Dance when I was a teenager and I was really lucky to have some fabulous teachers and directors working with me who were really inspiring and got us all to work really hard and research whatever we were doing a show about – for example we did a show called ‘Frida and Diego’ about Frieda Kahlo and Diego Rivera so you had a bunch of kids in Wales learning about Mexican revolutionary painters and Mexican culture and Mexican dancing – totally mad and brilliant (not sure our accents were that authentic though!). Mid Powys Youth Theatre won the National Youth Theatre awards twice and we got to come up to London to perform at the National Theatre – which was so exciting for all of us as teenagers as you can imagine.

And my dance teacher at Powys Dance gave me my first professional job; touring a dance piece around Wales – which was during my GCSE’s so I’d finish and exam and leg it out the school gates to jump in a tour bus, go and perform and be back in school the next day for another exam. I couldn’t have done any of that without the support of my parents so I’m really grateful to them for encouraging me to pursue the things I loved.

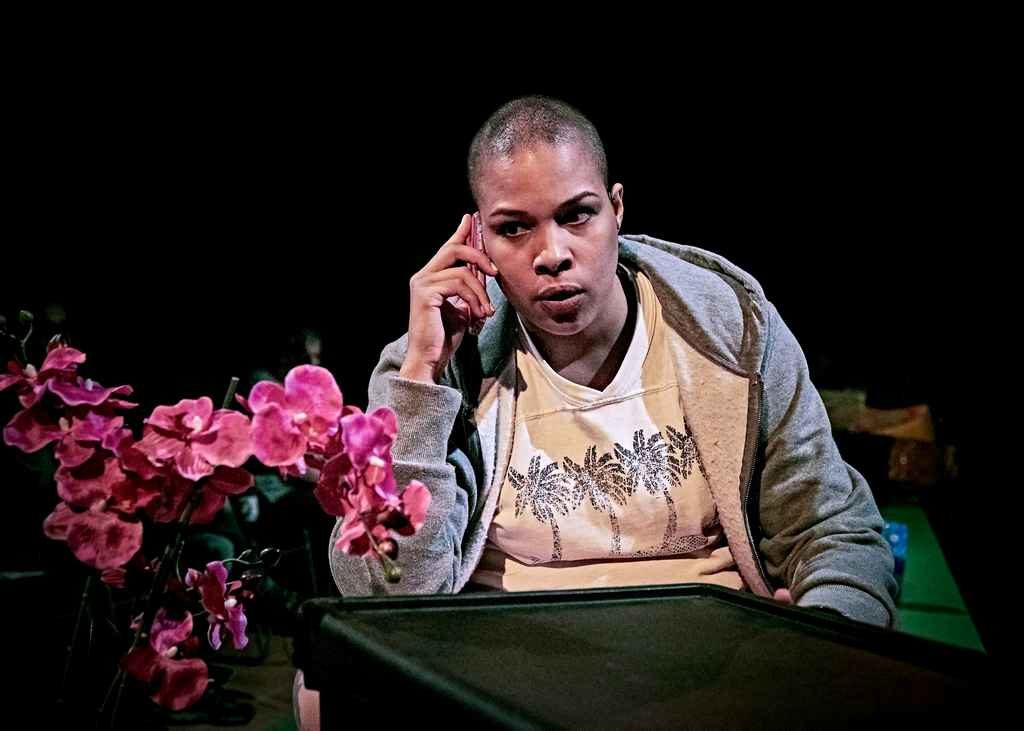

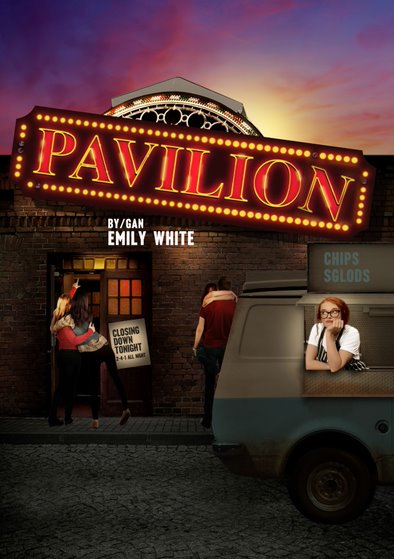

Your new play Pavilion opens at Theatr Clwyd this autumn before then playing at The Riverfront in Newport. The production has a wonderful tag line of “Dance.Drink.Fight.Snog” please tell us more!

The play is set in an old run down Pavilion where the local Friday night disco takes place every week and the whole community is out because the Pavilion is about to be closed down. There has also been a protest that day about the High School being closed and merged with another school in a nearby town – so everyone’s a bit on edge. One of the unique things about growing up in a small town is there’s only one place to go out and dance, so young and old have to socialise with one another and everyone knows everyone which makes for great drama and comedy. So it’s a play about the effects of austerity on a rural community but it’s also a loud, raucous, all singing, all dancing, funny night out in a town full of larger than life characters.

Pavilion takes place in a “small town in a forgotten corner of Wales.” As a Welsh writer how do you feel Wales has been represented on stage and screen recently?

We don’t see nearly enough stories about the Nations on our screens and stages and personally I think it’s important that we do, I feel representing the whole of the UK should be part of the diversity that theatre and television and film are aiming for. We have a divided country at the moment so the arts has a really important role to play in representing the parts of the UK that feel invisible and unheard – people within the London bubble need to see our stories too. How else will we begin to understand one another?

I’m interested in learning about other cultures and it’s been wonderful to see productions like Nine Night, Leave Taking or The Barbershop Chronicles and see a new audience in those theatres that are really excited to see their lives being represented on stage, I found it very moving to see that happening, I was watching the audience as much as I was watching the plays. I’d hope audiences would be interested in learning about Wales: a country right on their doorstep with a fascinating history and it’s own language that they know very little about. I have lived in London for 21 years now and in the theatre especially it’s rare to see a Welsh play about Wales, or a Scottish play about Scotland, Ireland gets a little bit more of a look in. Things are starting to improve on television with the BBC encouraging writers in both the regions and the Nations by creating writing groups that help them into the industry – I was part of the BBC Wales ‘Welsh Voices’ group this year in Cardiff.

And of course we have a very exciting boom of production companies starting up in Cardiff which have brought us some great TV shows like Keeping Faith and Hinterland – may they lead to many more! As far as films go Submarine was fab, Craig Roberts has written and directed some interesting films recently and Pride was wonderful (although I would have preferred a few more Welsh actors).

Tamara Harvey and the team at Theatr Clwyd have really invested and supported Welsh Playwrights. How did you become aware of the theatre and Tamara’s work supporting Welsh writers?

When I’d finished a second draft of Pavilion I contacted a tutor of mine at RADA, Lloyd Trott, he does a lot of work with emerging writers and arranged a table read, and workshop with RADA graduates and students. He suggested we arrange a rehearsed reading and that I invite Tamara to come along. She came up and saw the reading and then finally after a long hiatus she called me totally out of the blue (a year later) and said she wanted to do my play. One of the most exciting phone calls of my life!

I didn’t have an agent at the time so I had sent the play to every British theatre that had open submissions and received really glowing feedback from all of them but it was always ‘We loved it, it’s like a modern day Under Milk Wood but it’s not for us, good luck.’ Part of the problem being it’s a massive cast of eleven actors which costs a lot, theatre’s don’t have any money and I’m a totally unknown writer – so I really stacked the odds against myself ever getting this play on – looking back I should have written a play with two people in one room talking but unfortunately that is not the play I wanted to write! So Tamara and Theatr Clwyd have really done something quite unheard of and amazing by deciding to put it on regardless of those things I am eternally grateful to them for their support.

Get the Chance works to support a diverse range of members of the public to access cultural provision Are you aware of any barriers to equality and diversity for either Welsh or Wales based artists?

Well I feel I’ve answered this slightly already. There is a barrier in Welsh writers getting our work on outside of Wales. But I also think poverty is an issue – we need funding to be able support emerging writers and directors from working class backgrounds. If you’re from a really poor family, you can’t afford to be part of a residency if it’s not paid or it doesn’t help with accommodation that’s going to be a big deterrent.

In terms of public access, the lack of transport to the small number of theatres there are is a barrier – Theatr Clwyd is an incredible theatre but it is hard to get to if you don’t own a car – the council used to fund a local taxi company to lay on three buses a week that would collect anyone that couldn’t get to the theatre but with all the funding cuts that service is now gone. I think that’s a crying shame for the theatre and for the audience because it meant that the elderly, the disabled, young people who can’t drive yet and just people who couldn’t afford a car, could go for a night out. When I was a teenager we lived in a small town and my mum had to get rid of our car for a number of years because she was unemployed and there was no way to get anywhere to go and see anything.

If you were able to fund an area of the arts in Wales what would this be and why?

That’s such a difficult question because there’s loads of things I would like to fund. But I think youth engagement is really important so I would want to put funding into that – funding to make sure that every child has access to a youth theatre, a dance centre, an art class or a writing class, music whatever it may be – and crucially enough funding that the organisation is subsidised so that children whose parents are on benefits can still afford to go. All these groups allow young people to meet each other and encourage them to express themselves and to think about the world and their part in it. Art encourages empathy and there’s nothing more important than that right now.

What excites you about the arts in Wales?

I think it’s a really exciting time for the arts in Wales. The theatre scene in Cardiff has grown so much since I was a young, from home grown companies like Dirty Protest, Hijinx, and Chippylane to small venues like The Other Room and because of this there are a lot more Welsh writers around making their mark. The new BBC Wales building and the television production company boom means there are more jobs in that sector in Wales than there has ever been so getting into the production side of the business is now a real possibility for young people in Wales and doesn’t feel so out of reach. Theatr Clwyd are making great work in co-production with London theatre’s so is The Sherman, and NTW is touring round Wales taking projects to places that don’t have easy access to a theatre of their own – all really important, plus all these theatre’s are working with new writers which is fantastic.

What was the last really great thing that you experienced that you would like to share with our readers?

Another really difficult question because I’ve seen so much great work this year. But I guess the show which I can’t get out of my head is Cyprus Avenue by David Ireland – a writer from Northern Ireland – which was on at The Royal Court earlier this year. The premise of the play is: an old unionist in Belfast is suffering with dementia and believes his new baby granddaughter to be a reincarnation of Gerry Adams.

It was a surreal, obviously hilarious and at the same time deeply disturbing play that was an examination of blind hatred. The play could only really end one way and he certainly didn’t chicken out. You spent the entire play crying with laughter but with this growing unease at what was coming. He had us in the palm of his hand. It also made me realise I don’t know nearly as much as I should about Northern Ireland and then we’re back to what I was saying earlier about diversity and representation.

I love a play that is politically charged but manages to still be funny and entertaining. That balance of drama and comedy is, such an effective way to get an audience lured in and invested. Humour is so important. I talked about it for weeks afterwards.

(3.5 / 5)

(3.5 / 5)

(5 / 5)

(5 / 5)

(4.5 / 5)

(4.5 / 5)