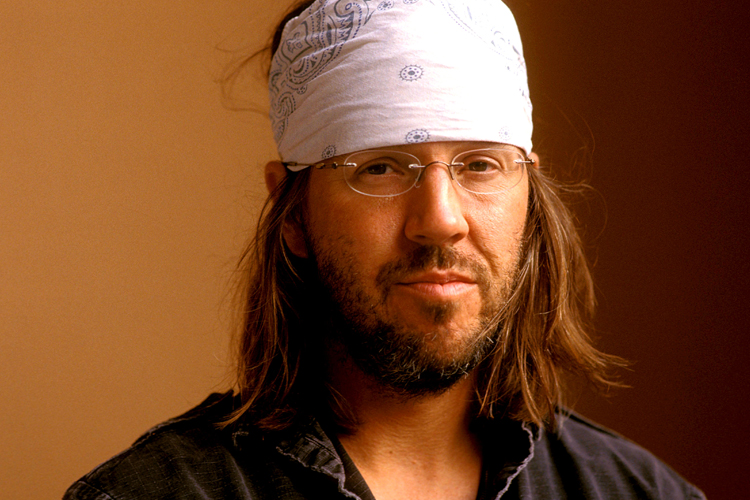

I don’t necessarily have a favourite novel of all time, but if I were ever pressed to choose a work of fiction that has captivated and has brought me the most joy whilst reading it I would probably opt for Infinite Jest by the late American author David Foster Wallace. It sometimes feels like a bit of a cop out saying this, or a bit cliché, because it seems as if many readers of my generation—well, in America anyway—would arrive at the same decision. Much like Nirvana’s Nevermind, Infinite Jest carved its way into the cultural milieu of the 1990s with such force that it almost goes without saying that it’s one of the greatest artistic endeavours of the decade—and perhaps even the century—within which it was produced. And in tandem with the music of Nirvana, its legacy owes much to (and is intricately wrapped up in) the counterculture of its time—or more specifically, a category of young people known colloquially as ‘Generation X’. By the end of 1996 (the year it was published), Infinite Jest had sold well in excess of 40,000 copies, and as of today its sales have exceeded one million, making it an enormous commercial success.

Yet when we analyse the success and popularity of Infinite Jest a bizarre paradox can be seen: loads of people bought it, but very few actually read it! This may have been in part down to its reputation as a complex and impenetrable novel, but its size was certainly a determining factor too. In appearance it’s practically a modern day War and Peace; a weighty tome coming in at over a thousand, densely written pages in length. Perhaps the reason that so many people bought it (particularly male college students) without ever reading it was so they could display it on their dormitory bookshelves as a symbol of the alternative, intellectual lives that they led, possibly in the hope of getting laid. But in my opinion, these two points are mere illusions. Yes the book is complex, but certainly not impenetrable, even with its often experimental and mutable prose: its contents are beautiful, moving, funny and thoroughly entertaining. And while it does take you on an intricately textured journey into the nature of humanity and society at large, it’s written in such a way as to make its philosophical meaning instantly perceptible, by striking at the heart of your own experiences as a human being. Referring to its size, superficially it does look daunting: I was most definitely intimidated by its heft to begin with. But because it’s such an entertaining novel it never feels like a chore to read; you become so invested in the story it has to tell that you just want to keep on reading and reading and reading. At one point I can remember noticing that I was just over halfway through, and this realisation disheartened me in a way because I simply didn’t want the novel to end.

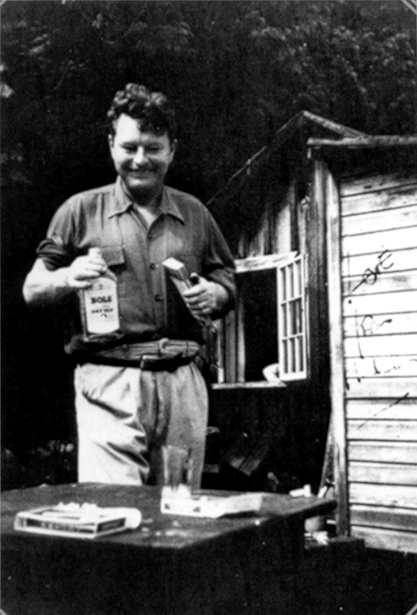

David Foster Wallace

I suppose the main reason I’m writing this piece is due to the fact that in the UK Infinite Jest doesn’t seem all that famous, even among avid readers. I’d never heard of it until a close friend of mine recommended it to me, and to this day she’s the only person I know who’s read it and who I can discuss it with. This is such a shame, as I see Infinite Jest as one of those novels that every reader, regardless of age, sex or background, should consume at some point in their lives.

In trying to sum up the plot of Infinite Jest, I find it helpful to draw on the TV show The Wire as a useful point of comparison: it’s made up of several stories which at first appear separate but which eventually come together to form a cohesive whole. And much like in The Wire, each narrative and story builds up to an astonishingly rich view of the fictional world within which the novel is set, where every little detail counts. This fictional world is set in the not-too-distant future, where the USA, Canada and Mexico have formed a political union and which now exist as a kind of superstate known officially as the Organization of North American Nations (O.N.A.N.). In addition to that of political space, the concept of time has also changed quite drastically, and is now governed by something called ‘Subsidized Time’, where each year is both subsidized and named after a certain corporate sponsor. We have, for example, the ‘Year of the Whopper’, the ‘Year of the Trial-Size Dove Bar’, and the ‘Year of Dairy Products from the American Heartland’, which all lead up to the ‘Year of the Depend Adult Undergarment’, in which the majority of the novel takes place. Indeed, the world of O.N.A.N. is completely dominated by corporate advertising, which impinges unrelentingly on the lives of its inhabitants and which seems to affect every aspect of their daily routines. The central hub of the novel’s plot is the city of Boston, Massachusetts and its immediate environs. Set within and around the city are three focal locations: the Enfield Tennis Academy (E.T.A.) where young, aspiring tennis prodigies are sent to develop their skills in the aim of becoming professional players; Ennet House, a rehabilitation centre in which drug addicts and alcoholics recover from their illness; and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (M.I.T.), from which a prominent radio show is aired. A significant chunk of the novel also takes place within the mountains of Tuscon, Arizona, where a politically- and philosophically-charged conversation between two characters ensues, which encompasses some of the main themes and messages that the novel attempts to express.

Modern day Boston, Massachusetts

Thematically speaking, it would be impossible for me to even scratch the surface of Infinite Jest’s ideas and motifs within a short online article, such as this is. But I will briefly discuss two of the most important ones. Addiction, both as an illness and a concept, represents an all-pervading presence within the novel; several key characters are battling their dependency to hard drugs like crack and heroin, principally those who end up as residents at Ennet House. As an ex-addict myself, I found this all very poignant, mainly because the ways in which David Foster Wallace deals with this topic are so utterly realistic and identifiable. A life of drug addiction is simple and manageable, while the alternative—the recovery—is almost unimaginably complicated as it runs the risk of leaving oneself open to feeling emotions that desperately need suppressing. Yet Infinite Jest shows us that drug and alcohol dependency are only a small facet of addiction, and that potentially harmful addictive tendencies penetrate each of our lives, whether we realise it or not. The inhabitants of O.N.A.N., for example, have access to a form of digital media known as ‘InterLace’, which allows them to watch any TV show or film or sports event (and so on) ever recorded whenever they want. In this sense, when reading Infinite Jest we are confronted with an entire nation addicted to watching TV, and anyone who binge-watches Netflix content today will find this hauntingly familiar. The acronym ‘O.N.A.N.’ is deliberately chosen here: it’s a reference to onanism, and it’s basically telling us that this fictional nation is consumed by addiction and hedonistic behaviour to such an extent that it might as well be continually masturbating all day, everyday. I guess what David Foster Wallace is saying here is that addiction forms a fundamental and inescapable aspect of human life, and that freedom from addiction (paradoxically) comes in the form of choosing what we may or may not be addicted to.

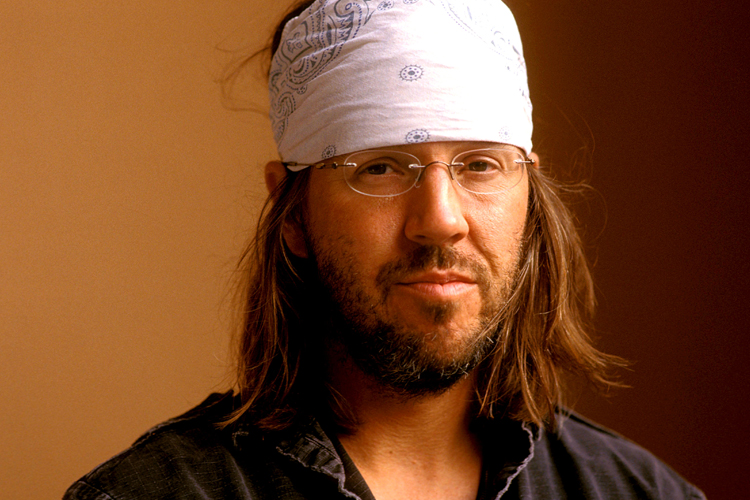

The addict’s perception of self

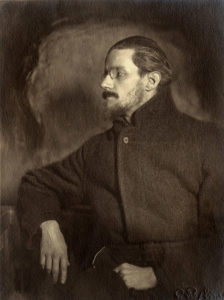

Another of the novel’s key themes is communication, or more specifically the transferal of thoughts and ideas from one person to another. This is represented primarily through the character of James Incandenza: a seminal filmmaker who becomes disillusioned with the avant-gardism of his earlier work and who later tries to communicate his ideas in a more accessible way through the medium of action movies. This obsession drives him to a life of chronic alcoholism and he ends up committing suicide by cooking his own head inside a microwave, which happens shortly before the novel is set. Later on, James Incandenza takes on an almost god-like presence in his ability to affect the lives and decisions of the novel’s characters, even from beyond the grave, and he may therefore be seen as an extension of the author himself. David Foster Wallace came from a strong postmodernist tradition (a movement known for its complex and often incoherent content), and it’s possible that within Infinite Jest he is desperately trying to drag postmodernism kicking and screaming into the 21st century, but in a far more accessible and entertaining form. In other words, it seems as if his yearning to communicate his ideas more coherently forms the entire basis of this novel, and that an inability to do so was a consistent source of fear for him. Yet this fear moves well beyond the realm of artistic expression; it encroaches into our own daily lives and thought processes, as a person’s failure to communicate their thoughts clearly to another person is surely a sign of their own insanity.

James Incandenza’s suicide

I’m not saying that Infinite Jest is one of the greatest novels ever written—I feel like there are very few people sufficiently qualified to draw that conclusion, and I’m certainly not one of them. I’m not even saying that Infinite Jest is perfectly written: there are parts that seem pretentious, even intellectually ostentatious. The insistent use of endnotes is a key example, which aren’t really endnotes at all but are actually integral elements of the novel itself, packaged in an academic way. But for me, one of the amazing things about Infinite Jest is that its story and its characters are so compelling, so thoroughly well written, that I’m able to forgive all of its shortcomings. And who knows, maybe upon rereading it I may even grow to love them. Once I finally finished reading this novel, I had the instant realisation that David Foster Wallace quite literally poured everything he had into it. It can be seen as a mirror to his own psyche—a near-perfect reflection of it. His passions, his fears, his intellect, even his own mental illness—which eventually led to his suicide in 2008 and which caused him to do some questionable things throughout his life beforehand—can all be picked out within the text. And upon researching the history of Infinite Jest, it’s easy to see why this is. The writer Mark Costello (who is David Foster Wallace’s former housemate), once intimated that the process of working on this novel kept David Foster Wallace from killing himself in the early 90s; he said that while he was writing it he, temporarily at least, stopped feeling bad about himself.

Overall, Infinite Jest is a truly incredible novel, and despite its reputation I believe it’s one that anyone can pick up and enjoy. It’s also a rather unique experience; I can’t really think of any other novel I’ve read that manages to create a fictional world that is both gargantuan in scope and encyclopaedic in detail, but which simultaneously revolves around an intensely character-driven plot. Thinking back on it, I really cherish the time I spent reading Infinite Jest, and I’m actually saddened by the idea that I’ll probably never read anything like it again.

by Rhys Morgan