The first image we see in Andrej Wajda’s Ashes and Diamonds is that of a cross on top of a small chapel. The camera pans down to find three men laying on the grass next to the chapel, one of them is sleeping. An innocent little girl appears and asks one of the men to open the chapel door for her. A nice summery image for a pleasant summer’s day somewhere in Poland. Then in the distance a car approaches, the men rush to their feet, each brandishing machine guns and tell the little girl to get lost. Bullets fly, the car comes crashing to a halt, the driver falls out, machine gunned to death. The passenger makes a run for it, bangs on the locked door of the chapel, but he has nowhere to go. The three men machine gun him to his death, as he falls he bursts into flames at the door of the chapel. One of the three men then panics, ‘let’s get out of here,’ he wails, and we realise that we’re not watching super cool hitmen but real human beings caught up in civil unrest in Wajda’s most humanistic of films. Later, after the three men have fled we realise that they’ve killed the wrong people as their intended target arrives on the scene. A worker surveying the dead bodies then asks, ‘can you tell us how long people will have to die like this?’ Ashes and Diamonds is a film that asks the toughest of questions.

Presented as part of Martin Scorsese’s “Masters of Polish Cinema” series, the film features in Scorsese’s list for his choice for the ten greatest films ever made in the 2012 Sight & Sound poll. The film is a key component of Polish new wave cinema, one of the most stylish of national cinema movements and just like the French new wave which came hot on its heels, Wajda and his fellow filmmakers managed to expand on the cinematic foundations laid forth by the Italian neo realists in the mid 1940’s.

Ashes and Diamonds is essentially the third part in Wajda’s unofficial war trilogy, although enjoyment of the film is not dependent on viewing the previous two. In the previous two films, A Generation (1955) and Kanal (1957), which both concern themselves with the Polish uprising during the Second World War, there is, despite the bloodshed amongst the upheaval of human morality, a great deal of hope and idealism. But come Ashes and Diamonds, this hope has evaporated and instead been replaced with despair. Even in spite of the fact that the Nazis have surrendered which people hear about over a loudspeaker yet barely react to, there is no Times Square esque V-J Day celebrations here, because for the first time since the war started, people can now envisage their futures and they don’t like what they see. Fighting the Nazis united them in hope, but now the war is over and the only people left to fight is themselves.

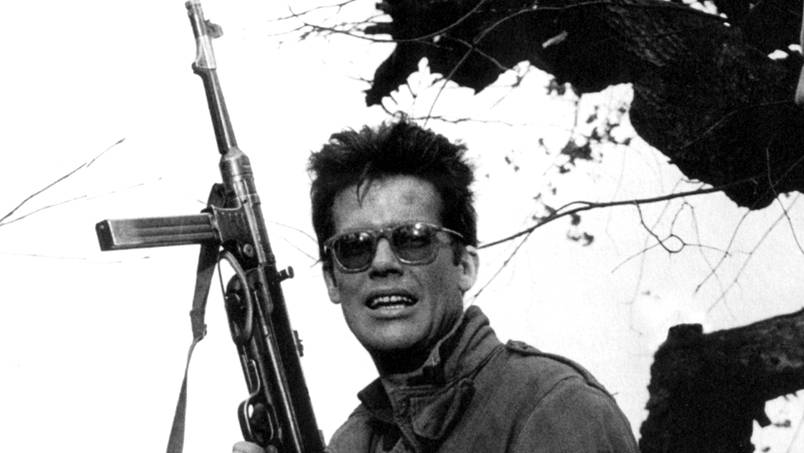

Set over twenty four hours in 1945, the overriding narrative of the film deals with the civil conflict between the pro-Russian People’s Army and the UK backed Home Army. The film is both a war tale and a tragic love story whilst also having the feel of an American hang out movie. The star of the film, Zbigniew Cybulski, incidentally one of the three shooters we meet in the opening scene, was often known, thanks largely to this performance, as the Polish James Dean. He certainly has Dean’s coolness and playfulness, whilst his impulsiveness throughout the film conjures up the image of Dean jumping from roof tops in Elia Kazan’s East of Eden (1955). Cybulski’s performance, his actions, his facial expressions, manage to capture the melancholic nostalgia of the story and of post war Poland, he says things like, ‘nothing in this country is serious anymore.’ He meets a girl, the wonderful and beautiful Ewa Kryzewska, who works at a hotel bar who says things like, ‘I don’t want any goodbyes or memories to remember when it’s over.’ This is a film where every line of dialogue has meaning and significance.

On the surface at least, Cybulski is the star of the film, but the true star of Andrej Wajda’s Ashes and Diamonds is Andrej Wajda himself. The whole film is a one hundred minute masterclass in cinematic framing. In one scene, Wajda frames Cybulski’s collaborator in arms Andrej, played by Adam Pawlikowski, in a close-up as he talks on the phone inside a telephone booth, over his shoulder is Cybulski leaning on a bar, then behind Cybulski in walks Communist Commissioner Szczulka, played by Waclaw Zastrzezynski, the man who Cybulski and co were originally sent to kill. In one shot through expert framing Wajda manages to convey the entirety of the film’s emotions and conflicts with stark simplicity. Throughout the film Cybulski keeps coming face to face with his past, in one scene he sees the crying fiancé of one of the men he killed in the opening sequence. Cybulski stares at her and Wajda holds and holds Cybulski’s gaze in a close-up. There are no words spoken yet by dwelling on Cybulski’s face Wajda manages to convey all the actor’s emotions, it’s almost as if we can hear his thoughts. This is pure cinema.

The images in Ashes and Diamonds are so profoundly striking it is a film that could be watched and understood with the sound turned off. The film ends with an unforgettable sequence that you will carry around with you long after the final credits have rolled. It’s visual poetry from start to finish.

Ashes and Diamonds (12)

Poland/1958/104mins/subtitles/12. Dir: Andrzej Wajda. With: Zbigniew Cybulski.

At Chapter Arts Centre from June 7th – 9th.

– See more at: http://www.chapter.org/ashes-and-diamonds-12#sthash.2nExviZK.dpuf

Tag Archives: Chapter Arts Centre

Review The Ladykillers, Chapter Arts Centre, Cardiff by Barbara Michaels

The Ladykillers at Chapter Arts Centre, Cardiff

Original screenplay by William Rose

Adapted by Graham Linehan

Production by Everyman Theatre

Director: Marie-Claire Costly

Reviewer: Barbara Michaels, Third Act Critic

Rating: [3.00]

Murder and mayhem are the buzzwords for William Rose’s comedy-thriller The Ladykillers. For those fortunate enough to have caught a screening of the Ealing Studios 1954 motion picture, Everyman Theatre’s production of the adaptation by Grahan Linehan will bring back fond memories. Who could forget the iconic performance by theatrical icon Alec Guinness as the crafty (and dotty) Professor Marcus?

Take an eccentric old lady living on her own with her parrot and add a gang of crooks masquerading as musicians who rent a room in which to plan a robbery and the scene is set for a series of mishaps. When the old girl, Mrs Wilberforce, discovers what they are up to there is only one solution – to bump her off before she turns them in. But that is not as simple a matter as it might seem – and neither, as it transpires, is the elderly widow who despite her old fashioned appearance might be more than a match for the bumbling ineptitude of the amateur criminals.

Characterisation and pace play a major part in putting on a play of this genre, where a great script full of humour should raise delicious giggles among the audience from start to finish. On opening night this sadly was not the case. It was not until a second half with increased momentum that the performance really got going and we were given a heartening glimpse of what the cast are capable of achieving. It is reasonable to expect things to improve later in the run, for Everyman Theatre has a good track record – their Oh What A Lovely War last year was tops.

As the “master criminal” Professor, Paul Fanning is believable although relying overmuch on twiddling his overlong scarf. Not quite dotty enough for this critic, although the Prof’s darker side is well presented in Act II. As for the rest of the gang, Steve Smith’s sharp suited Mafia-type Louis is spot-on and Arnold Phillips suitably military as Major Courtney. As Harry, the youngest of the crooks, Sion Owen settles into the role nicely in the second half.

Now we come to Mrs Wilberforce, played by Ruth Rees who admirably displays both the mobility problems of increasing age, limping around the stage as is suitable for one later described as Mrs Lopsided, and the finickiest of advancing age in another era. Nevertheless, Rees’s portrayal is still a tad too lively for the part – a few more wrinkles added in make-up might help. Loved the costume, though, particularly in the tea party scene and the posse of old ladies is fun – Lynn Hoare gets it just right as the gushing Mrs Tromleyton.

Full credit to the set designers for their clever use of every area of the stage and for props for some wonderful touches – wonky picture, grandfather clock et al, not to mention the interesting musical instruments.

Runs until Saturday May 23rd.

REVIEW Oh What A Lovely War, Everyman Theatre by Barbara Michaels

Oh What A Lovely War at Chapter Arts Centre, Cardiff

By Joan Littlewood

An Everyman Theatre Production

Director: Jackie Hurley

Musical Director: Lindsey Allen

Choreographer: Richard Thomas

Reviewer: Barbara Michaels

Rating: [4.00]

Portraying the horror of the trenches and the politics behind World War I, Everyman Theatre’s production of Oh What A Lovely War joins the ranks of performances in memory of those who fell that have taken place all over Britain during the past centenary week.

Bringing to the stage once more Joan Littlewood’s iconic 1963 Theatre Workshop production, complete with Pierrot costumes and a backdrop of photographs from the war zones as well as staggering on-screen statements of the numbers lost in what was supposed to be “the conflict to end all conflicts” is an ambitious undertaking. Everyman Theatre rises superbly to the challenge, wisely choosing to present the piece as “A musical play,” rather than musical theatre, although where to draw the line between genres is never clear-cut.

All the more credit, then, to director Jackie Hurley for staging a performance of this profoundly moving piece of theatre, which at times gives rise to an audible intake of breath from the audience as the ever-increasing numbers of the soldiers who died are flashed on the backdrop, yet managing to present in tandem with this an upbeat element which gives a balance to the overall result.

How, indeed, could it be otherwise – despite the grim reality of the core subject matter – when you have a talented young ensemble cast that includes some excellent singers and dancers? Songs that depict to a T both the era and mores of the time – from that of the title to familiar music hall song and dance numbers such as ‘I’ll Make A Man of You, ’ the foot-tapping ‘Row, Row, Row,’ and lump-in-the-throat ones such as ‘Keep the Home Fires Burning’ are memorable. Choreographer and nimble-footed dancer Richard Thomas has done sterling work here, as has Musical Director and on-stage pianist Lindsey Allen (despite grappling with a slightly out-of-tune piano.).

Change of mood is crucial and on the whole handled well, although occasionally erratic, as can happen on a small stage with minimal props. As the fighting escalates, military leaders thrash out the strategies of waging war, putting forward disastrous solutions that only prove them to be blindly oblivious to what is really going on, while the young soldiers who joined up with such youthful enthusiasm slowly come to realise that the “War games” are not at all what they expected.

As a sombre cloud hangs over Europe, the deafening noise of exploding shells brings a powerful sense of the grim reality of war. Amid a number of poignant moments, the one that perhaps more than any tears at the heartstrings is Christmas Day in the trenches. The emotional impact of the sound of the German soldiers singing ‘Stille Nacht’ floating across No Man’s Land, followed by the exchange of gifts and fraternization between the two sides, is huge, giving rise – not surprisingly – to sniffs from some of the audience.

Focus of this production is, quite simply, to honour those who lost their lives while depicting the behind the scenes wheeler-dealing and obstinacy that resulted in such tragically large numbers of young men losing their lives.

In other words: War is a dirty business.

Runs until Saturday, November 15th, at Chapter Arts Centre, Cardiff.

Review Caitlin, Chapter Arts Centre, Cardiff by Barbara Michaels

Credit Warren Orchard

Choreography: Deborah Light, Eddie Ladd and Gwyn Emberton

Director: Deborah Light

Caitlin; Eddie Ladd

Dylan: Gwyn Emberton

Reviewer: Barbara Michaels

Rating: [3.5]

Based on the writing of Caitlin, the wife of Welsh poet Dylan Thomas, this dance production tells of her life with the poet through the medium of a meeting of Alcoholics Anonymous which she started to attend some twenty years after his death. Similar in style that of the one-woman show performed at the Sherman Theatre in 2003, it could equally have been named ‘The Agony and the Ecstasy.’

Caitlin’s recognition of the destruction wrought upon her life is portrayed in a series of dance moves, many of them violent in the extreme. In focussing on the turbulences of the Dylan marriage, director choreographer Deborah Light adheres closely to Caitlin’s own perception of her alcoholism and her life. The athleticism and technical skills of Eddie Ladd as Caitlin are showcased brilliantly, although there is a tendency to over- use of repetition, which can be tedious at times. One thinks of Ladd as a dancer but Light also allows her to speak, albeit briefly. Her speaking voice enthrals as much as her dance technique and makes a considerable contribution to Ladd’s characterisation. Her reiteration at intervals throughout that, while Dylan was a poet, “I could have been a dancer” adds poignancy to the overall projection of chaos, with dancers and furniture crashing around the stage for much of the time.

Ladd’s boundless energy is phenomenal, as is that of Gwyn Emberton, as Dylan. Many of Emberton’s dance moves require him to roll around the floor or balance precariously on a pyramid of stacked tubular and plastic chairs that teeter ominously. The said chairs are an integral part of the production, being used by the dancers use not only to represent actual objects – a baby’s pushchair, for instance – but also mood. There is no set, and these are the only props, barring a paperback book and four glasses of water with sweets in. Seated on some twenty chairs of the same ilk are the remainder of the cast (actually the audience), representing the members of the AA meeting which Caitlin is addressing.

In the year which marks the centenary of Dylan Thomas’s birth and the 60th anniversary of the iconic Under Milk Wood, it was inevitable that all aspects of his life would be explored in theatrical performances both nation and world-wide. His lifelong battle with alcoholism has been well documented; that of his wife Caitlin possibly less well so, In portraying this, and showing that while in some aspects it bound them together, Light’s production shows how eventually it destroyed not only their marriage but both of them.

Runs at Chapter for two more performance: Thursday October 30th at 6.30 and 8.30

Performances on Mon 3 + Tue 4 Nov at Volcano, The Iceland Building, 27-31 High Street, Swansea.