Tensions run high in Black Sheep Theatre’s debut production Fear of Drowning at Chapter this week; it’s Elli and Steve’s wedding day, the bride has gone AWOL and Steve’s best mate Deano is waterboarding her brother Tim in the hotel bathroom.

After an initial flash-forward to Tim’s unfortunate predicament, the play begins with Elli and her brother, Harry Potter fanatic and ardent Environmental Warrior, Tim arriving in a budget hotel (whose lightbulbs we quickly learn do not meet international efficiency standards) having fled Elli’s imminent vows to possessive partner Steve.

Elli’s feeling out of her depth. Is marrying Steve a massive mistake or maybe commitment really is for her? To know for certain, she resolves the only solution is to go and see her ex, Ben, one last time. When Steve and Deano turn up, Tim is quick cover for Elli, resulting in a stake out in the hotel room where underlying class tensions come to a naturally humorous head.

Fear of commitment, possession and both the loss and perceived pejoration of identity through a new shared one are recurring themes throughout this eclectic piece of drama which is as funny as it is a clever statement on underlying class prejudice. There is a brilliant irony in Tim’s unshakeable belief that he is saving Elli from Steve’s possessive ways whilst simultaneously trying to shield her from the tragedies of Steve’s ‘type’, fuelled by an insurmountable fear of losing his sister that itself borders on obsession.

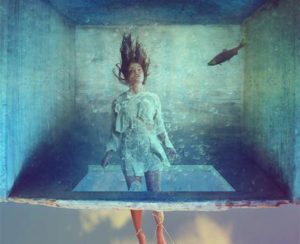

Through Tim’s sense of helplessness as he slowly loses his sister (and of course his very literal experience of being water-boarded by Deano); Elli’s uncertainty of the unknown and reluctance to take the plunge and commit to Steve and Deano’s evident feeling of treading water in a dead-end position where he is underpaid by his supposed best friend, the play is a perfectly realised metaphor of drowning which reflects the intricacies of each characters unique situation and lack of control.

When Steve abandons the others in a last-ditch attempt to pursue Elli we encounter what was undoubtedly the most surreal and wholly unanticipated scene of the play; Lee Mengo’s comically menacing portrayal of Deano lightly ridiculing Tim quickly escalating into a ketamine induced recollection of how he first met Elli aboard HMS Genesis a post-apocalyptic research ship on a Mission named Noah’s Ark… On Steve’s return, the continuation of this notion of being out of control, only this time in a very literal sense, escalates further still, manifesting itself in the pairs decision to waterboard Tim.

There is a slightly unsettling scene at the end with Tim in evident turmoil at the loss of his sister who despite everything decides that Steve is the one for her. Yet this is once again interrupted by more of the unexpected absurdity which made this play so enjoyable.

From Deano’s holographic memory, a ketamine riddled BLT and the moral conundrum of whether or not you can waterboard a trouser-less man, Black Sheep Theatre combine sharp wit with a stark and honest portrayal of class prejudices to produce a work well deserving of its place as Runner Up in the inaugural Wales Drama Award. Fear of Drowning is a credit to writer Paul Jenkins and Black Sheep Theatre and a sign of great things to come.