Hedda Gabler will not be coerced. It’s the mantra of a general’s daughter, the battle cry of a woman so enmeshed in the art of war that she keeps loaded pistols in her living room. Henrik Ibsen’s convention-demolishing heroine raised eyebrows (and tensions) when she first stormed onstage in 1891, and the Sherman Theatre’s bold new version proves that Hedda is still as fresh, furious and fascinating a character in 2019 as she ever was.

Adapted from the original by Brian Friel, we follow Hedda Tesman (née Gabler) as she as her husband George return home from their honeymoon. Having recently received his doctorate, George is hopeful of gaining a much-telegraphed professorship – until the resurfacing of his academic rival, and Hedda’s former lover, Eilert Løvborg, threatens to upend the fragile new life they have built together. Chelsea Walker’s electrifying direction keeps mystery and character motivations simmering just below the surface; under her careful, artful eye, the stage is always thrumming with movement, which not only propels the drama along at a nimble pace but makes the world (though encased in a gorgeously hyper-real theatrical set) feel lived-in and authentic.

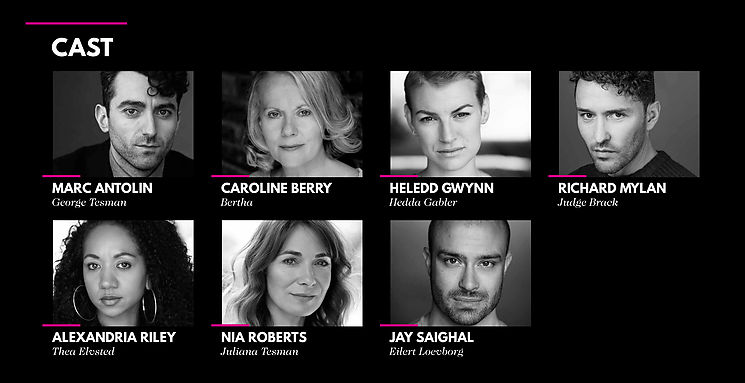

As Hedda Gabler, Heledd Gwynn is astonishing. Brutal, blunt and unbending, she demands space and attention, majestically spreading her arms like a King holding court – because although Hedda is a wife (and possibly an expectant mother), she defies and often transcends the strict binaries of gender and the behaviour dictated therein. Hedda wears her hair short and her feet bare; the most feminine she allows herself to be in appearance is the glamorous silk dress she sports throughout – a militaristic green gown she wears defiantly like armour (she is the only character who does not change her clothes – or anything else, for that matter – in the second act). And yet Gwynn meticulously threads a vein of vulnerability into Hedda’s precipitous façade, deposits of entombed emotion that Hedda battles to suppress and, if need be, destroy.

After Gwynn’s stellar turn, the other most overtly impressive performance is from Richard Mylan as Judge Brack, a sinewy nerve of malevolent machismo who is perhaps the closest Hedda has to an intellectual equal. As both a man and a judge, Brack is a repulsively-drawn sleaze of the highest order who delights in wordplay and innuendo as a means of making himself look powerful and sophisticated. As the sole representative of the law, Brack is a petty, pernicious piece of work; a man who, despite his profession’s aim to locate the truth, deals in gossip, hearsay and lies. Mylan deliciously articulates his every word with a sort of Wildean lasciviousness, and his every moment onstage feels unsettlingly dangerous.

On the opposite end of the spectrum is George Tesman, Hedda’s blissfully clueless beau, endearingly played by Marc Antolin. George is just so lovable that his oblivious adoration of Hedda even as she ridicules him behind his back is one of the most heart-breaking elements in an already-tragic story. Antolin treads a fine line in making George’s naïveté sweet without slipping into bumbling foolishness; his interpretation is a far more sympathetic take on the character than most – even if did manage to turn their honeymoon into a six-month long research trip. His doting aunt Juliana, tenderly played by Nia Roberts, seems to understand more of Hedda’s foibles than she would ever passive aggressively hint to her nephew, but Roberts brilliantly plays the role on several different levels at once, hinting at a more intricate inner life that other versions might gloss over – meanwhile Caroline Berry as stalwart servant Bertha watches proceedings with soundless intensity.

The ever-excellent Alexandria Riley once again shines in a complex role. As Thea Elvstead, Riley represents a more conventional femininity than Gwynn’s Hedda, escaping one troubled romance to start another, and finding herself caught in the dead space in between men who continue to fail her. She has devoted herself to the cause of Løvborg’s redemption and is willing to put in the invisible emotional labour to help co-author his revolutionary new book uncredited. Although Thea is eager to raise Løvborg up at her own expense, she is presented as a far more bold, brave person than Hedda, who despite her brash callousness admits herself a coward in catering to her phobia of scandal above all else – and the thorny rapport between Thea and Hedda is one of the drama’s most engaging and multifaceted relationships.

As a heroine in 1891, Hedda was unlike any woman in fiction at the time – her existence was a triumph in itself, every cruel act a defiant reclamation of agency that other women (fictional or otherwise) were then denied at a systematic level. Even though Hedda remains frustratingly oblique about her intentions (for the most part), that she has the freedom and privacy of her own thoughts and motivations was a privilege afforded to few women in the literature of her era. It is even more poignant when considering how Hedda is treated as property and possession to everyone in her life – especially to Brack, who views her as uncharted (and as-yet unconquered) territory, and even to dear, darling George (who takes on more of the emotional, empathetic woman-coded duties of the domestic household), who starts mapping out her entire life the second he learns that he has a progeny on the way, exuberantly uncaring of what she has to say in the matter.

Tragically, perhaps the only one to see her as a person is one she dehumanises the most: Eilert Løvborg, wonderfully portrayed by Jay Saighal. He is the one to call Hedda by her maiden name, by the name we know her, by the name that reflects her true self. Saighal is captivating in the role, projecting the image of a genuinely kind but self-destructive person brimming with love and beauty but unable to channel it into healthy, rewarding pursuits – his infatuation with Hedda a prime example. The moment where Løvborg secretly touches Hedda’s hand as an unknowing George flips through the honeymoon photo album is the most sensually-charged moment in a play that also features the judge crawling towards Hedda on all fours. That brief, almost-hidden moment of contact is a subtle, gorgeously romantic moment that represents all that was, is and could be between two people who just keep missing the chance to be together.

The superb acting is bolstered by a truly spectacular set, gloriously designed by Rosanna Vize in a way that is both edgily creative and deeply symbolic. The stage is decadently austere – all sharp lines and stark colours, nothing homely in sight save for the battered old piano which maybe represents Hedda’s deceased mother; a cage hangs ominously over the domestic square like a sword of Damocles, ready to ensnare her. The set is both specific and universal enough to enable a multitude of readings: perhaps it represents the reductive domestic sphere, or a psychoanalytic manifestation of Hedda’s internal mind; perhaps a domesticated purgatory or a metaphysical courtroom – or all at once? Ash falls from the ceiling at times; a real fire burns in a hidden compartment under the floor; in parts the stage is littered with flowers, symbols of pure, pretty, uncomplicated femininity – and Hedda takes a blowtorch to them. It’s utterly mesmerising.

Giles Thomas and Robert Sword’s anxious heartbeat of a score throbs ominously as tensions rise, and the cast wait their turn while sitting in chairs at the back of the stage, watching. As a purgatorial judiciary of peers, they sit in judgment, but also don’t seem to exist unless as pawns in the machinations of Hedda, who is the only actor onstage at all times – even when she is not participating in a scene, she remains the focus of it, standing imposingly at the centre of the stage as others talk about her. At one point George waxes lyrical about how there is only one Hedda, but she is already two – Hedda Gabler and Hedda Tesman. The true Hedda lies behind a door to which we are never given access; though the drama’s vibrant brush strokes paint only a partial portrait, we learn that Hedda is a deeply complicated, contradictory and confounding person. We may not agree with her, like her, or even sympathise with her – but we are her, in all our wondrous complexity.

It was a privilege to be a part of the post-show panel, along with Hannah Morgan (Head Above the Waves), David Mellor (Lecturer of Sociology, University of South Wales), led by Tim Howe (Communities & Engagement Coordinator, Sherman Theatre). It was such a joyful panel to be a part of and honestly my favourite so far – not least because Hannah

memorably dubbed Løvborg ‘hot bleedy guy’ and made my night! It was particularly special because Cardiff’s Law and Literature module was out in force, including our brilliant students and fearless leader Professor Ambreena Manji. We have been studying the play in our classes and it has been wonderfully rewarding to hear each of the students develop and express their own individual interpretation of the story, characters and themes. Although Hedda Gabler is not obviously legal on the surface, a deeper reading reveals legal issues at play such as gendered criminal behaviour, theft, co-authorship, property law, blackmail, and encouraging suicide (and that’s just the non-spoiler list!) Reading the play with these issues in mind can help to historicise law and explore its real-world effects and implications. The panel culminated in the question of whether Hedda ultimately has a choice in the end – I can only urge you to see this stunning production and answer that question for yourselves. Hedda Gabler is playing at the Sherman Theatre until 2nd November.

(5 / 5)

(5 / 5)

(4 / 5)

(4 / 5)

(3 / 5)

(3 / 5)