What does it mean for a writer to be great? Is it measured by the amount of work they produce, or its quality? The way they are perceived by others, or how they see themselves? Perhaps ‘greatness’ is just the lie of venerating a ‘chosen’ few; a lie which inch by inch lifts that glass ceiling ever higher.

By these metrics, a voice as brilliant as that of Dorothy Edwards (1902-1934) is lost in the maelstrom of literary machismo. The black sheep of the Bloomsbury Set, she was raised by firebrand radicals in South Wales and yet somehow dislocated from her working-class roots (she attended Howell’s private school, if on a scholarship, and later studied Greek and Philosophy at Cardiff University). In the London scene of literary greats like Virginia Woolf and E.M. Forster, she was the ‘Welsh Cinderella’, raised from the pits of the Valleys into dazzling notoriety in her own lifetime – but after her death, her books went out of print and her suicide note became her most cited work.

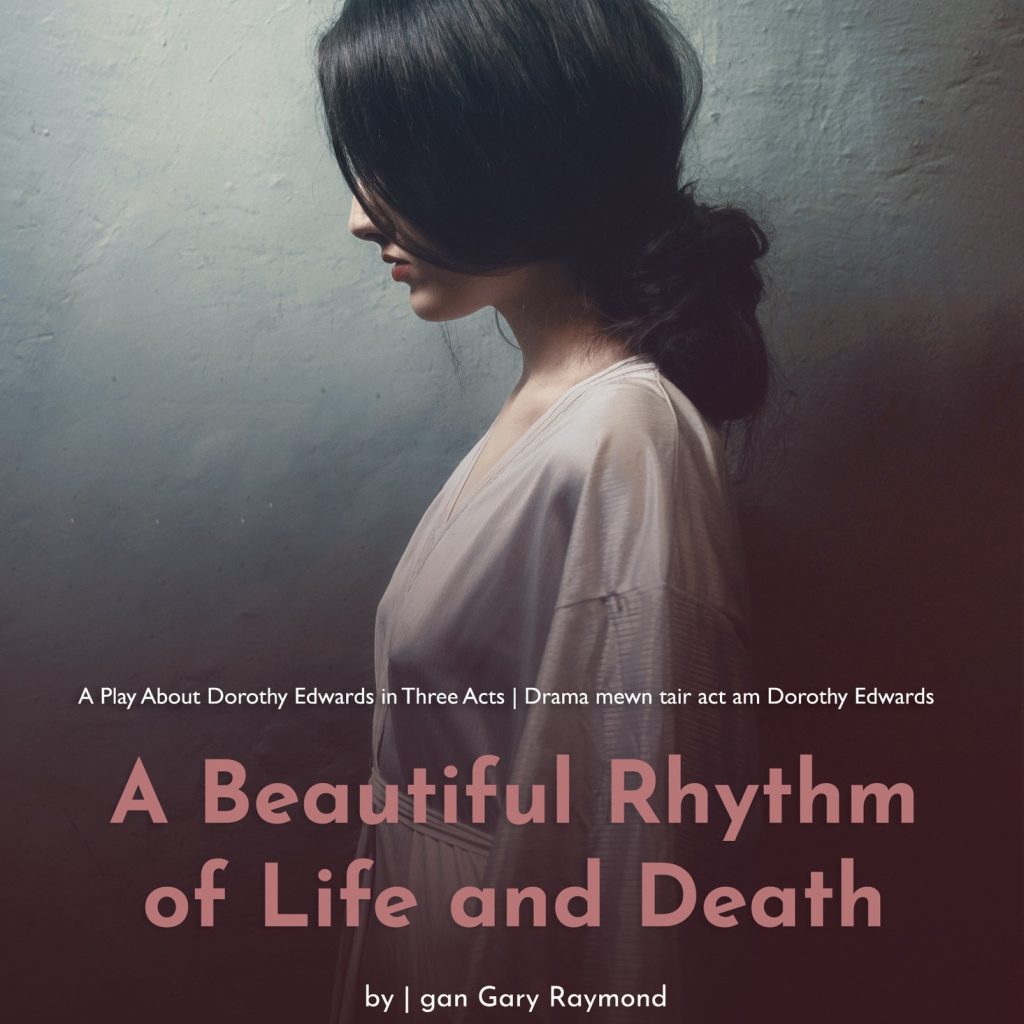

It is this complicated legacy that Gary Raymond’s new play sensitively examines. Directed by Chris Durnall, ‘A Beautiful Rhythm of Life and Death’ starts at the end of Dorothy Edwards’ life and moves backwards through twin storylines: in the past, Dorothy (Angharad Matthews) is inducted into London’s writing elite by David Garnett (Jâms Thomas); in the present, actors Meg and Byron, also played by Matthews and Thomas, debate how best to bring her story to life.

The play’s title – taken from a line in Winter Sonata (1928), her only novel – is an apt description of the drama, which toys with musical and emotional tempos. Matthews and Thomas are captivating, playing a convivial game of cat and mouse in which you are never quite sure who is hunting who. Thomas is equal parts charming and chilling as the Svengali-esque Garnett, who always seems to place himself physically higher in the space than his ‘ingenue’. While he might have benefitted from the same costume flourishes given to Dorothy (e.g., adding braces and a waistcoat for extra texture), Thomas’ performance is nothing short of transformative.

Matthews is radiant as Dorothy, a flame who refused to dim her glow. There is a quiet defiance to her performance that embodies the stoic passion of Edwards’ heroines; women who were pushed to the margins in the interwar period. She was an outsider even among the bohemians of Bloomsbury, whom another famous Dorothy (in this case, Parker) said ‘lived in squares… and loved in triangles’. Dorothy’s affair with a married cellist, her engagement to her Philosophy Professor, working as live-in carer for Garnett’s son: all of these relationships blur boundaries; triangles on triangles, like the sonata form which underscores Dorothy’s work. Even the stage – a square room with its triangle of wooden decking – plays with geometric shapes. The fact that it is designed by Matthews means that we are watching two hidden architects at work.

And she pulls the strings from the very start. The live score by the luminous Stacey Blythe manifests Dorothy’s melodious thought processes: but as Matthews descends the steps for the first time, she slams down on the keys. This is her story, after all – at some points, she strides out in front of the audience and stares us down, as if daring us to forget it. Raymond’s soulful script, and Matthews’ lyrical performance, convey Dorothy’s abiding love for words: their codes and cadences, the way that just 12 notes and 26 letters can capture all the beauty and chaos of the world.

Durnall’s direction is a live if invisible thing: kinetic and coy, like the current that pulls a river. David and Dorothy circle each other, dynamics shifting, power crystallising. The sense that she was always thinking, always writing, with pen in hand or not, is ever-present, especially in the vibrant second act. Writing is her pole star: while people flit in and out of her life, that love never leaves her. Company of Sirens have worked their magic once more, and never is this clearer than in the exquisite closing scene, in which Dorothy finds true synthesis with another Welsh wordsmith (Glyn Thomas, author of The Dragon Has Two Tongues). It is an effortless coda that leaves Dorothy at a moment of pure synthesis. It is a slip of linen on the breeze; a single sustained note, that carries on even when darkness falls.

A Beautiful Rhythm of Life and Death is produced by Company of Sirens in collaboration with Chapter and Arts Council Wales, and performs at Chapter through 3 June. There are BSL-interpreted and audio described performances, and one matinee: more information and how to book tickets here.

What a beautiful story and what an amazing article of wonderful thoughts the way you describe this story is mind blowing and heart wrenching. The life of Dorothy is very tragic it is truly sad that she committed suicide and that only after her death did she get the fame and recognition that she deserves. In this unfair and unkind world we only get known when we are gone. Many artists after they died their paintings then became important and they are sold in the millions but those artists never saw such fortunes when they where alive.