(4 / 5)

(4 / 5)

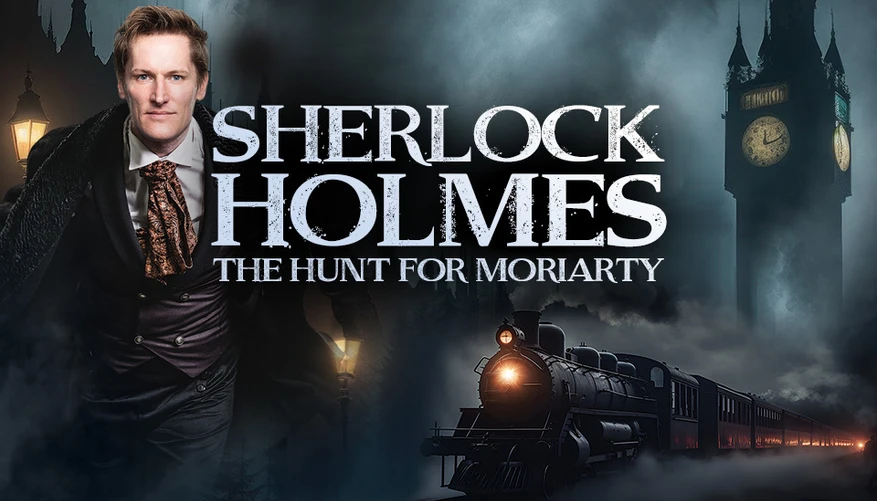

Having been lucky enough to see Blackeyed Theatre’s award-nominated production of Oh What a Lovely War at the same theatre in 2024, I knew I was in for a treat with this world-premiere adaptation- in which we see four classic Sherlock Holmes mysteries intertwined to make one thrilling new adventure.

Blackeyed Theatre is one of the UK’s leading touring theatre companies, with over twelve years’ experience of bringing exciting, high-quality work across the UK.

“After working with Blackeyed on two previous adaptations of Conan Doyle novels (The Sign of Four and The Valley of Fear) it was really exciting to be asked back to create something a little different for our third Holmes collaboration. It’s been fun capturing the pace, the spirit and the character of Doyle’s original adventures, and our hope is that, like the stories themselves, The Hunt for Moriarty will keep audiences gripped – and guessing – along with the great detective himself, right to the last” Nick Lane, Writer and Director.

The stage is set but is perhaps not what we would expect from 221b Baker Street- the apartment is burnt out, and we can’t see much aside from a few doors, some chairs, and a table. Enter our narrator for the evening, Dr John Watson, perfectly portrayed by Ben Owora who leads us into our tale and the events leading up to the fire. The plot is intricate but fast paced and the set is versatile- transforming cleanly from 221b Baker Street to an underground station, a theatre basement, a gentlemen’s club and so on. Sound and lighting offer additional atmosphere and projections on the back wall provide the audience with a visual aid reflecting the action on stage (i.e. a letter that’s being read, a note that’s been found etc.) as well as assisting with scene transitions- an underground map, billowing flames, a waterfall.

Mention must be made to the movement within the piece- from the slick scene changes to the fight choreography and the clever physical theatre of the Diogenes Club- the togetherness of the gentlemen seated, trying to read their newspapers in peace makes for an amusing watch! There are lots of standout moments like this which make this production sparkle.

The cast are superb and deal with the large amount of dialogue wonderfully- the production is lengthy at 2 hours 45 with a 20-minute interval (unsure of the 7.45pm start!) and in honesty, felt like it should have ended at ‘case-closed’! However, the title somewhat gives away the fact that we’re going to be heading to the Reichenbach Falls at some point during proceedings, so the numb bum had to be endured for at least another 20 minutes!

The character transformations are executed beautifully, with thoughtful costume and accent changes that make it easy to tell who’s who — and ultimately, whodunnit! Pippa Caddick plays all female roles from Mrs Hudson to Irene Adler and switches between them with confidence and clarity. Eliot Giuralarocca and Robbie Capaldi also handle four or five characters each with ease. However, special mention must go to Gavin Molloy, whose portrayals of five characters are so distinct that it’s easy to forget Lestrade and Moriarty are, in fact, the same actor!

To me, Holmes isn’t quite manic or quirky enough- Knightley portraying him as a more composed detective than fans are used to. There’s an air of madness bubbling, but it never quite comes to fruition.

That said, even with its long running time, the show dazzles with originality, cleverness, and style- any Sherlock Holmes fan would be mad to miss it. Elementary, indeed!

Sherlock Holmes: The Hunt for Moriarty continues its run on March 10th at The Dukes, Lancaster and finishes on May 23rd at the Northcott Theatre, Exeter.

Sherlock Holmes and the Hunt for Moriarty – Blackeyed Theatre

Cast:

Ben Owora- Doctor John Watson

Mark Knightley- Sherlock Homes

Pippa Caddick- Mrs Hudson, Violet Westbury, Irene Adler, Hilda Trelawney-Hope

Gavin Molloy- Inspector Lestrade, Louis LaRotiere, Professor Moriarty, Alex Trelawney-Hope, Herbert Fennell

Robbie Capaldi- Sir James deWilde, Hugo Oberstein, Ronald Smith, Don Chappell

Eliot Giuralarocca- Mycroft Holmes, Col. Valentine Walter, Wilhelm von Ormstein, Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, Will Parfitt

Creative Team:

Playwright / Director- Nick Lane

Composer and Sound Designer- Tristan Parkes

Fight Director and Choreographer- Rob Myles

Set Designer- Victoria Spearing

Costume Designer- Madeleine Edis

Lighting Designer- Oliver Welsh

Projection Designer- Mark Hooper

Education Advisor- Ben Mitchell

Company Stage Manager- Jay Hirst

Assistant Stage Manager- Duncan Bruce

Set Construction- Russell Pearn

Producer- Adrian McDougall

(5 / 5)

(5 / 5)

(3 / 5)

(3 / 5)

(4.5 / 5)

(4.5 / 5)