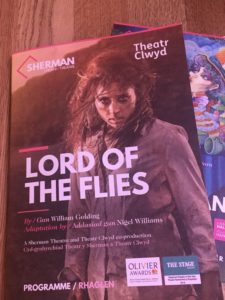

I will be the first to admit that I have had a love/hate relationship with William Golding’s Lord of the Flies. I was one of the many to study the 1954 novel during secondary school and, while I liked particular elements, I was certainly not a fan. However, mainly through a love for the audiobook, the novel has continually grown on me and now I would say it is a firm favourite which I will re-read multiple times.

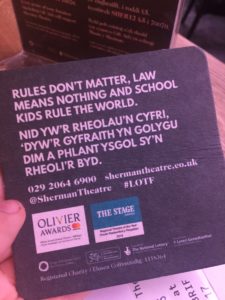

As this novel is one so constantly studied in school, due to the layers of imagery, intriguing characters and intriguing presentations of societal and bodily issues, I was immediacy intrigued to see that Lord of the Flies has now been adapted into a play by Nigel Williams which is currently showing at the Sherman Theatre. However, in order to fully review this play in the context of one which is studied so frequently, there will be spoilers for both the plot of the novel and the show and I will also be discussing some ways in which the play deviated away from the novel’s plot in order to make these clear to anyone studying this production in light of the novel. Therefore, this review will be a long one.

Lola Adaja gives an intricate professional stage debut as Ralph. I feel that she balanced the complex sides of Ralph in both opposing Jack but also partaking in the early chaos. The transition between his more childish side in interacting with Jack when they first meet on the island to his role and chief and the heartbreaking final transition back into childish weeping were suitably intriguing and heartbreaking to watch at once. Gina Fillingham’s performance as Piggy felt as if risen directly from Golding’s novel. A delicate balance between comedy and depression for order Fillingham, from her first moments, ensures that piggy’s presence is known despite Jack’s protests.

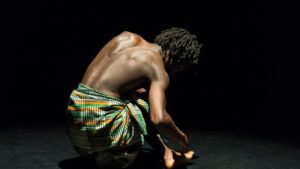

You may have noticed Williams’ biggest change in adapting Lord of the Flies from novel to stage. All male boy characters, while keeping their original names, are now played by women and all mentions of ‘boy’ are changed to ‘girl’ in-keeping with this. Honestly, when watching the play, in terms of watching the story unfold and the narrative, I barely noticed the change. Rather than wrapping the story around this change, instead this casting and adaption choice folded itself into the preexisting narrative. Therefore, I feel that this production is a good example of showing that this change can be done without compromising any major themes of the narrative.

I feel that this was certainly aided by the construction of the island around the actresses. James Perkins’ design ensures for suitably intricate routes through wooded forests and heightened cliffs which give settings for the action. This design expertly balances the audience’s image of a literal island but also hints towards the island as the construction of small boys, or girls, in this case, playing at civilisation. Also, a true highlight of this production is Tim Mascall’s lighting design. Right from the opening moments, the lighting is epic and this continues throughout the production. These two elements combined to make my jaw drop in the entrance of the parachutist which highlights one of the first darkest moments of the narrative and I truly enjoyed watching the lighting and the set design combine to enhance the narrative. Similarly, I feel that the atmosphere of this production evokes that of Golding’s original novel in Philip Stewart’s sound design. Stewart interestingly combines both the sounds of drumming and atmospheric noises in very interesting places, such as Jack’s first intention to divide the group, with the sounds of howling, shouting and crying by the cast to really bring all of these elements together.

William’s adaption of a more contemporary Simon worked very well and, in combination with Olivia Marcus’ skilfully quiet but active role, this really brought the character to a far more relatable point with the audience. I was also very pleasantly surprised that the production took the plunge and decided to portray Simon as having an anxiety-induced epileptic fit, rather than only a feint as it has been previously portrayed in films. While I cannot speak for the exact accuracy of the movements I do appreciate this decision due to the original vagueness of its presence in the novel and I feel that this aids the relatability of Simon in this production.

I will also say that the end of Act One, Simon’s death, is really the height of the production as the cast, sound, set and lighting design all come together. The moment itself is the best example within this production of the drama and epic features of Golding’s narrative and imagery as the sounds of the cast and practical effects ensure you cannot move your eyes away for a second. After the height of the moment, I love the intricate character moments of Piggy and Roger being the only ones to look at Simon’s body constantly after the act has been done. Following this, however, is one of the highlights of Adaja’s professional debut. The intricate detail of the spotlight on Simon once everyone, except Ralph, leaves as Ralph slowly turns to look at him and begin to sob. I feel that this was a really intricate way to do this scene and I really appreciated it as someone who has and will study the novel.

However, this production does feature significant changes which I, personally, was not a fan of due to the aspects of character and narrative which they changed. The main changes concern Simon, Piggy and Roger. The first is Simon’s scene with the titular Lord of the Flies, a pig’s head from Jack’s earlier hunt. In the novel and the subsequent famous film adaptations, the Lord of the Flies is always a major point of focus and truly a highlight, even if it is, as it is supposed to be, nightmare fuel. In fact, this scene is one of the many which have caused some readers to count this novel as a horror novel. This moment is vital to Simon’s character construction as he has a ‘conversation’ with the head, commonly agreed to be in his head even though commonly presented as two-sided, which foreshadows events and always stands out. However, in this production, this conversation simply blended into the background of the end of Act One. The pig is simply on the ground, rather than on a stick as it usually is, and while there is a small hint at the Lord of the Flies voice the conversation is purely voiced by Simon. While this is interesting there is no mention of the name Lord of Flies or the foreshadowing lines which are vital. The play could have been staging this as only Simon can hear these lines but this just leads to the conversation not being the true highlight of creepiness and narrative that it should have been.

The second is the parachutist. While I loved the entrance and the presentation of the parachutist, it began to distract me in the second act because of a major narrative change. While Simon does find the parachutist as she usually does and her vital lines regarding its humanity are still present they miss the vital point of Simon’s goodness and wish for the preservation of humanity’s goodness in Simon’s untangling and freeing of the parachutist who is then moved away from the island by natural causes. This was a change where I can see why the result of the action does not seem vital but I do not understand the reason for keeping the parachutist on the island when its time in the narrative has ended and the original actions do aid characterisation.

However, the purely biggest change is Piggy’s death. This play does weirdly change the circumstances surrounding Piggy’s death. While her glasses are stolen by Jack they are never broken which is again strange as the breaking of Piggy’s glasses before they are stollen is representative in the novel of the gradual breakdown of law and order. This could have been due to the time constraints as Act Two did feel shorter in terms of narrative but it is something to bear in mind if you are studying The Lord of the Flies. After this, Piggy’s death is not the same as it is in the book. Rather than Roger consciously choosing to release a bolder which kills Piggy by striking him on the head, and breaking the conch in the process, this play instead stages Piggy as being scared by Roger, Maurice and Perceval shouting which leads her to fall from the cliff and the conch in consciously broken by Roger with a rock. Again, while I can see that this form of Piggy’s death is easier to stage it is a curious change which must be made clear to those studying it. Another thing to bear in mind is that Hannah Boyce’s wonderfully creepy Roger is far more vocal than he is in any previous version. While it is nice to get a further insight into one of my favourite mysterious characters some of this vocalisation is badly placed in the tone of the play.

Therefore, overall I’m giving Nigel Williams’ Lord of the Flies ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️. While major narrative changes must be kept in mind for those studying the novel alongside this play, this play is an excellent theatrical version of the setting and general points made by Golding’s novel. The set, lighting and sound design of this production is a highlight of practical theatrical effects which allow the wonderful cast to really mould themselves into their characters and the setting. This leads to a really enjoyable experience in watching this cast find their characters and explore the setting while also making the events of the narrative suitably uncomfortable to watch.

Lord of the Flies is running at the Sherman Theatre until the 3rd of November and you can get your tickets here: https://www.shermantheatre.co.uk/performance/theatre/lord-of-the-flies/

Vicky Lord

@Vickylrd4 [Twitter]

(4 / 5)

(4 / 5)

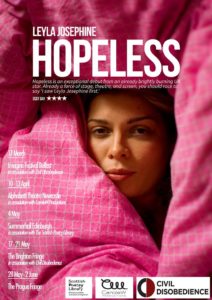

(2 / 5)

(2 / 5)