Photo credit: Tristram Kenton

(4 / 5)

(4 / 5)

Performance artist Marina Abramović knows a thing or two about death. Earlier this year she almost died and remarkedly got a boat over to London for her few months here (health prevents her from flying). She is stretched between time at the Royal Academy, South-bank Centre and English National Opera. The latter of which is what this review shall discuss.

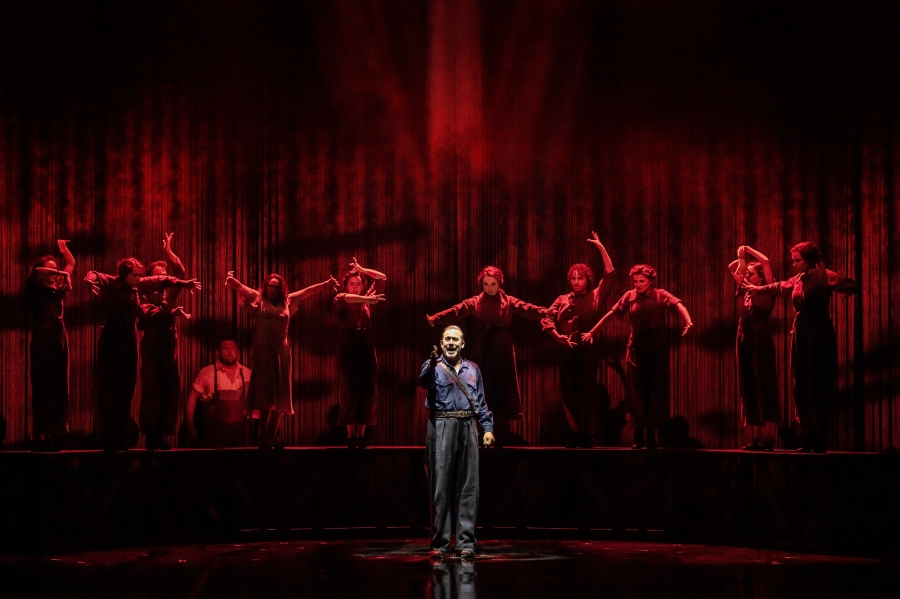

Her obsession with opera diva Maria Callas started in childhood, Marina overcome with tears upon first hearing Maria on the radio. Marina’s artwork has always been extreme in command, duration, content and context. I was curious just how this would go down with opera audiences, most known for conservatives tastes and values. Well, traditionalists will find favour in these 7 deaths, each one of Callas’ most revered arias from Verdi, Puccini, Donizetti and Bellini. So seven sopranos treated us to these famous arias, each one as wonderful as the last. Some ENO trained ladies and other international stars really made this show shine. Marina during these hits remained static in bed as Maria.

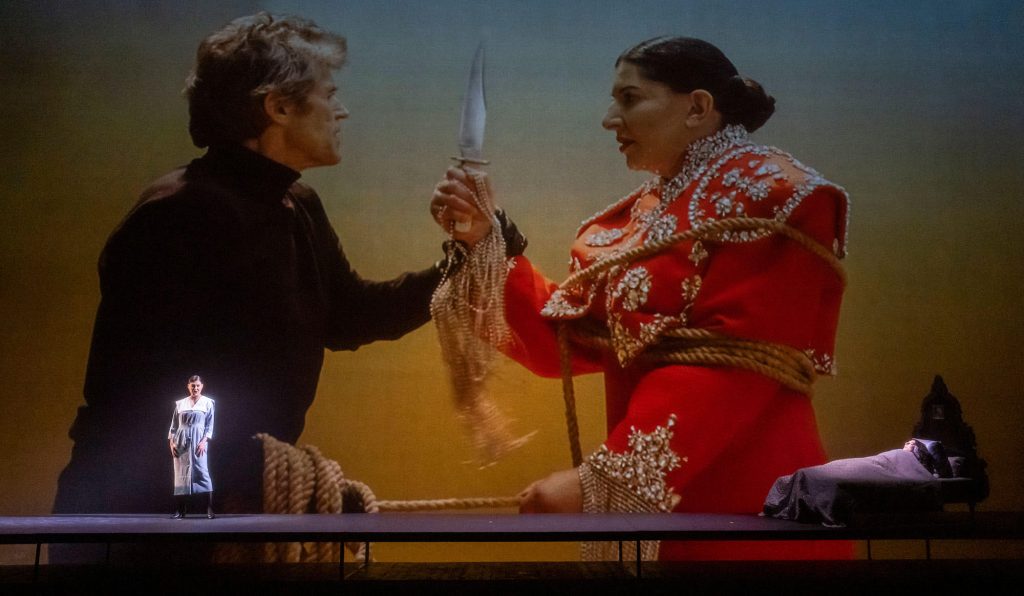

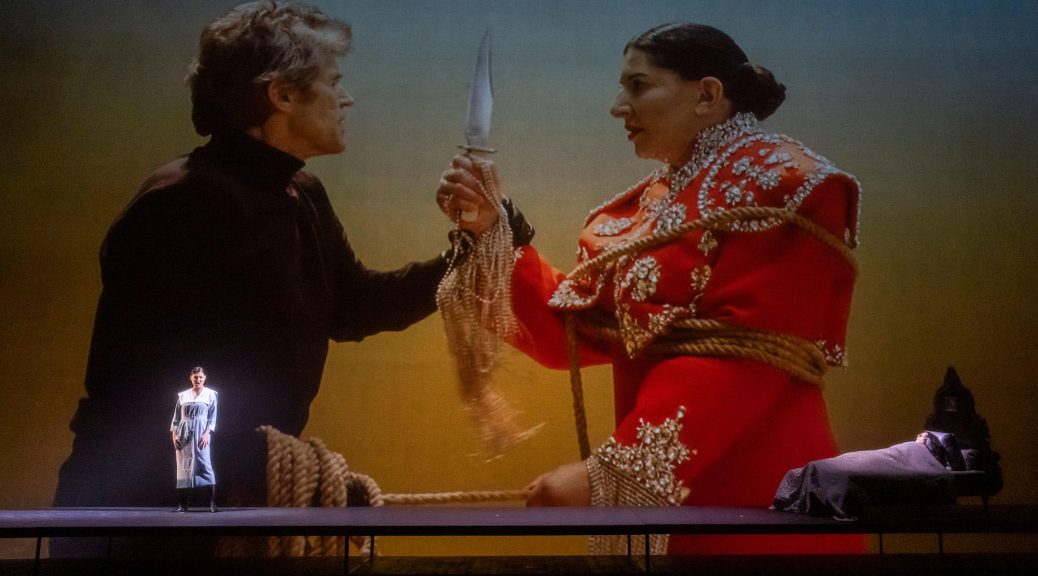

Fellow Serbian Marko Nikodijević composed the fibers between the arias, creating a subtle yet somehow harsh soundworld. The video work of Marco Brambilla was hypnotic, sprilaing vortex and storms, another highlight. Marina even planned the set with Anna Schöttl, a lavish tribute to the Callas aparment in Paris. Giant video work towers over all on stage, Abramović and Willem Dafoe muck about with various inspired threads on the deaths of these operatic heroines: Tosca’s plunge, Norma’s immolation, Carmen’s stabbing et al. More performance art is here as you’d expect and some of it is captivating, other times a little on the nose. The Ave Maria from Verdi’s Otello paired with Marina covered in huge constricting snakes might just be the best thing you’ll see on stage this year.

The whole opera builds to the seventh airas and we get a scene change after it. Marina directs herself with idiosyncratic spoken word, as she has done during the intermezzos all evenings. Here, her guide to life reach the steps for Maria to end her life: getting out of bed, opening the curtains, smashing a vase on the floor and leaving the room. The seven sopranos come back in, still dressed as their maids outfits to tidy up the mess. Marina returns all golden and sparkly, she does her thing as we finally hear Callas, as her Norma is cut short and the show ends.

One of the more stanger and wonderful operatic exercises this year.

Its runs till 11th Nov 2023.

Marina Abramović at the Royal Academy runs till 1st Jan 2024

(3 / 5)

(3 / 5)

(3.5 / 5)

(3.5 / 5)