In this latest in the series of Playwright interviews Peter Cox gives an overview of his career to date, his time working for National Institutions, access to the arts for all and his hopes for the future. Interview by Director of Get the Chance, Guy O’Donnell.

Hi Peter great to meet you, can you give our readers some background information on yourself please?

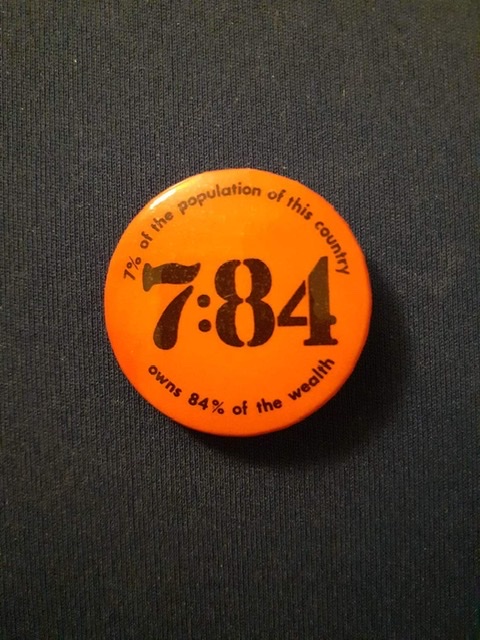

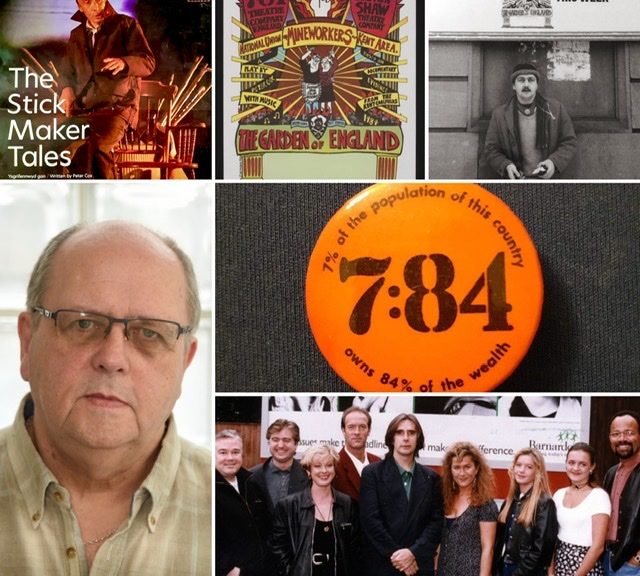

I began my writing career at the Royal Court Theatre in London where I won the George Devine Award for most promising new playwright in 1983. My stage plays have since been commissioned and performed by companies throughout Britain – including 7:84 Theatre Company, the Royal National Theatre, Belfast Opera House, the Wales Millennium Centre and National Theatre Wales.

I’ve written and developed film and television drama for the BBC and various independent companies. My radio drama has been broadcast on BBC Radio 3 & 4 but I’m maybe best known as the writer of 227 episodes of the acclaimed Channel 4 drama serial, Brookside, between 1986 and 2003. During this time, I was a lead member of the writing team that created multiple-strand stories for more than 2,400 episodes.

Throughout my career writing drama for theatre and television I’ve been privileged to work alongside, and with, masters of these forms including Samuel Beckett, Edward Bond, Billie Whitelaw, Michael Bogdanov, Danny Boyle, and Sir Phil Redmond CBE. The experience of learning alongside people who are working at the top of their profession is unbeatable and led me, in turn, to a commitment to mentoring theatre makers and writers.

Alongside my writing work I’ve been very active in the Creative Industries sector in Wales including creative leadership and advocacy in community arts, cultural policy making, economic and cultural regeneration, broadcast radio and television drama production, professional theatre, youth theatre, live music promotion, carnival, and cultural tourism.

I’m a founder trustee and ex-Chair of CARAD (Community Arts Rhayader and District), a Registered Charity that has developed a regionally significant Rural Community Arts and Heritage resource that’s brought more than £5 million of inward investment into Mid-Wales. During my leadership term CARAD facilitated the active engagement of more than 118,000 members of the community and helped to inspire and deliver over 650,000 hours of community participation and engagement in arts, heritage, and media projects.

In the 2010 New Year’s Honours list I was awarded an MBE for services to community arts – in essence, an acknowledgement of the amazing vision and hard work of many local people. In 2018, along with an ex-Brookside writer colleague, Judith Clucas, I co-founded a new media production company, Portsea Media Ltd.

So, what got you interested in the arts?

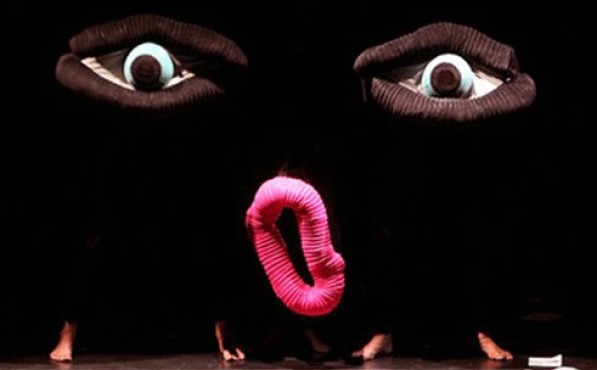

My earliest theatre-going experiences fuelled my desire to pursue a career in the performing arts. My first, on a teenage school-trip, was watching Peter Brook’s ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’, with its rock-circus staging and Bottom being given a clown nose rather than an ass’s head. A few years later, as a drama student, I was awestruck watching the fabulous giant puppetry of Swiss theatre troupe Mummenschanz. Soon after I was deeply moved and inspired by Lindsay’s Kemp’s extraordinary, ‘Butoh’ influenced, movement-theatre production of ‘Flowers’ at Sadler’s Wells. There are visual stage images from all three productions seared into my memory to this day.

In each of these shows, the non-traditional theatre techniques and visual language used were incredibly powerful and profoundly enhanced the storytelling. Primarily though, I was conscious of the way my emotions, imagination and creativity were provoked by these vividly effective, stylised, and subversive theatrical approaches. I was hooked.

Why do you write?

I write to try and harness the vast numbers of ideas that just keep bursting out of my sub-conscious mind. I write to try to capture and express moments of extreme crisis, of powerful emotions, from rage and hate to love and grief. I write to make an actor’s blood run faster and to make audiences laugh and cry.

As both a playwright and screenwriter, I’ve researched in, and written about, many socially and politically challenging environments, including: the Bogside in Derry in 1982/3 just after the Hunger Strikes, across British coalfields during the 1984/5 Miners Strike, in Southern Sudan – a war and famine zone, during the Troubles in the Falls Road Belfast 1988/89, and so on. At the heart of all this work there are real people facing very real, and serious, crisis points in their personal and community lives.

Those are stories that need to be told.

Can you tell us about your writing process? Where do your ideas come from?

I watch the world – politics, journalism, human behaviour and frailty, social trends etc… and generate ideas on a daily, if not hourly, basis. I never block any of my own ideas – I note them down, then they either get used or not. Sometimes they might resurface years later in an entirely new context.

I use a diverse range of process techniques, like T Cards and colour coding for structure, but my approach to storytelling is always the same, whatever the form… find a compelling character, or group of characters, and put them into a story that pushes them up against and beyond their own boundaries. The challenges they face, both mirror and echo the challenges that audiences face every day.

Can you describe your writing day? Do you have a process or a minimum word count?

Getting into my ‘writing zone’ is crucial. Blanking out all the extraneous noise from life and the world around me. Once there I honestly can’t say how the magic happens – when the words flow it’s an alchemical process. Researching and note-gathering are replaced by something akin to ‘channelling’ as characters, action, dialogue and images form in a kaleidoscopic visualisation.

I never judge or edit as I go – that comes later. I’m completely committed to revising and re-writing and I’m not afraid to write twenty or thirty drafts or more. I’m a strong advocate of the strength and power in a good relationship between writers, directors, and dramaturgs. I work on the understanding that writing is a form of improvisation on the page. I never ask, ‘Do you like what I’ve written?’ Always just, ‘How can it be better?’

Do you have a specific place that you work from?

When I worked as Writer in Residence with No Fit State Circus – on three site specific shows -my ‘standing-desk’ was a wheelie bin, out in the open air, with my writing files and laptop perched on top of it. I wouldn’t swap that experience for the world, but when it comes to writing every day, often for very long hours, I prefer my desk in my office space at home.

You began your writing career at the Royal Court Theatre and won the George Devine Award for most promising new playwright. We recently interviewed playwright Diana Nneka Atuona about her play Trouble in Butetown. Her script was recipient of the 2019 George Devine Award for her play then titled, ‘The Boy from Tiger Bay’. What role do awards and prizes play in a writer’s career and what difference, if any did it make to yours?

Huge congratulations to Diana. Winning the George Devine Award opened many professional doors for me, and I still place it high on my CV. Just as important though – was that it gave me a huge confidence boost and a validation of my writer’s voice.

I think it’s important that all ‘competitions’ should take the process very seriously. They need to be run with integrity and with good, sensitive communications. Giving thoughtful, considered, and professional feedback should be at the heart of the process – that way, everyone who enters is a winner.

I was fascinated with some Tweets you shared recently on a commission from The Royal National Theatre touring Welsh Miner’s Welfare Halls, where you also worked with 7:84 Theatre Company. How do you come to be involved in this project?

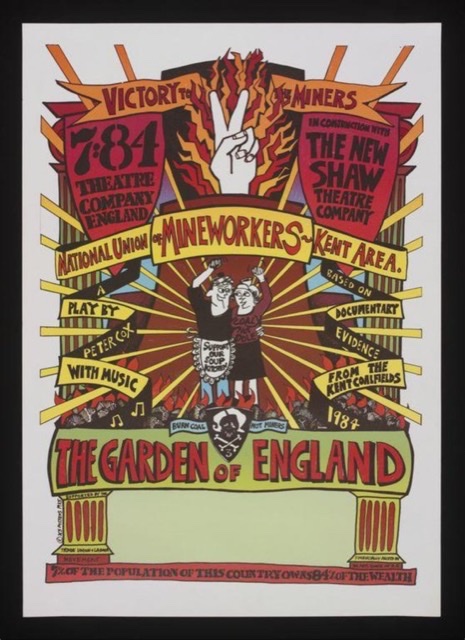

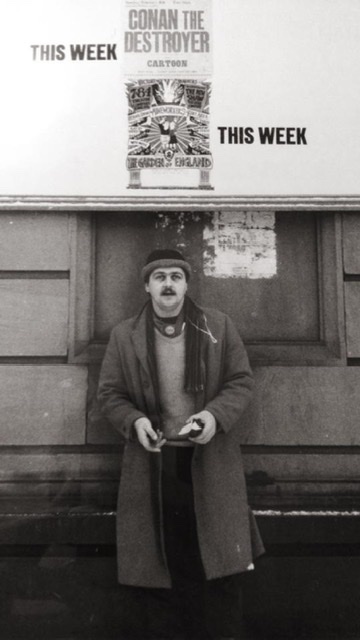

Just after winning the George Devine Award, I was commissioned by Peter Gill, Associate Director at the Royal National Theatre, to go into the Kent Coalfield to live with a militant striking miner – and then to create a verbatim play taken from interviews with miners for the duration of the strike. I travelled to every coalfield across the rest of the country, interviewing and researching on picket lines, mass demos, in soup kitchens etc.

After the first version of the play was done at the National, (The Garden of England, directed by Peter Gill), I was asked to write a touring show with songs – inspired by that verbatim research – for 7:84 Theatre Company (England). We played some amazing huge venues to thousands of striking miners and their families – with the buses that brought the audiences being sponsored by other trade unions and using volunteer drivers. (Opening night in front of 2,500 in Sheffield City Hall, second night another massive audience in Newcastle City Hall, then Manchester Town Hall.) Our Wales venue was the Parc and Dare and it was an extraordinary night, as was the rest of the tour!

Then, in a strange turn of events, once the strike was over, Peter Gill commissioned me to go back to Kent to conduct another whole sequence of interviews in the defeated mining community. Once again I created a powerful piece of verbatim theatre, but one which was very different in tone to the first two. The two verbatim pieces played in the Cottesloe Theatre at the National Theatre.

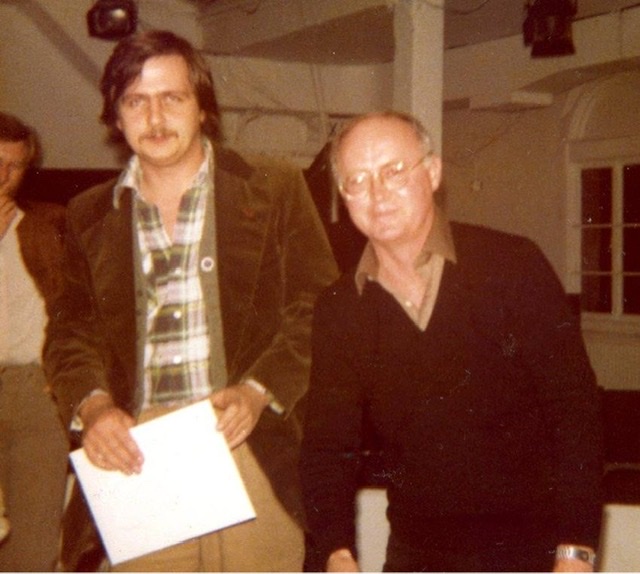

My connection with 7:84 was a big influence on me. I was very lucky to get picked up as a young playwright by such a theatre visionary as the late John McGrath who founded the company. John was extremely encouraging to me and gave me various opportunities. He enabled me to go on the road with the company in both England and Scotland, as a form of apprenticeship. He commissioned me and I wrote several plays for 7:84. He put me on the 7:84 management committee. I owe him a lot. He had a fierce intellect and was extremely shrewd and analytical – always pushing societal boundaries and hierarchical cultural constructs. Working so closely with him inspired me to do the same – something I try to do with every new project I undertake.

What role do you think National Theatres and Playwrights have in telling the narratives of the citizens of their respective nations?

I’m a solid believer in the importance of National Theatres, and I was one of the first playwrights to join the National Theatre Wales Community Writers Group when it was created online.

To be a good playwright you must care in equal measure about your characters’ and your audience’s lives. You need to be adaptable and flexible to create a wide range of characters and stories. You need serious commitment, stamina and staying power. You need to be ready to shed tears as you dig into the depths of your own life experience to bring those emotions to life in your characters. You need to love drama, and the power it has, to affect people’s lives. All these things apply to being a good National Theatre as well.

Peter wrote The Stick Maker Tales for National Theatre Wales in 2018

A large part of your career was spent writing episodes of the Channel 4 drama serial, Brookside, between 1986 and 2003. During that time, you were a member of the writers’ team that created multiple-strand stories for more than 2,400 episodes. You have said about your work on Brookside that “As you might guess I love story and the power of story metaphor in people’s lives.” We often see the term, “Writing Team” on long running serial dramas, can you share how this process works for the writers involved?

A Writers Room, or being on a Writing Team, is most commonly associated with American TV Drama Series & Serials. Breaking Bad for example, has a formidable reputation for the strength of its Writers Room – one of the reasons it has been so globally successful. Brookside story-lined with the Writers Room model – right from the day it started in 1982.

During my time on Brookside there would be twelve to fourteen writers on the team at any one time. We’d meet with the producers every six months to determine long-term story potential for all core characters. Then we’d meet for two days every month, in storyline sessions led by the Producer and / or the Exec Producer, where we’d intensively thrash out a block of twelve episode outlines at a time. We’d then go on to be commissioned individually to write single episode scripts – or possibly two or three for more experienced writers. While in the Writers Room we’d fight for stories, find twists and turns, generate the drama, seek out the humour and push the political and social boundaries as far as we could. We’d argue fiercely about politics, sex, religion etc… to the extent that, on one occasion, Security was called to attend as someone had reported a fight was taking place!

Writers Rooms don’t suit all writers, and they can be quite attritional places. Often there’s a high fall-out rate, and on shows like Friends they’ve been identified as being brutal and unforgiving. All of that said, when they work well, and when they suit you, it can be a fantastic system to work within. I had the great fortune to write for Brookside for eighteen years and my time in the Writer’s Room was like a monthly injection of the best drug going – intensely focused and collaborative creativity. I developed huge respect for my colleagues and for their commitment to driving our series to be the best that it could be. The fact that people still stop me, and talk about stories from over twenty years ago, is a great tribute to the effort we made at the time to tell the best stories we could that viewers would identify with.

In news just announced this week I’m very pleased to see that all episodes of Brookside have been digitally remastered and are due to be shown on STV – a free to air streaming service. I’ve no doubt that many of the stories that we told across the 80s and 90s will still resonate in the viewer’s lives.

Are there any particular storylines that you are most proud of during your time on Brookside?

Tough question. I was part of the Writers Room Team that generated storylines that ran through more than 2,400 episodes. I wrote 227 episodes which is a huge amount of broadcast television drama. To give you some idea of scale… just writing my episodes alone would be around three million words. By the time the team has story-lined and scripted over 2,400 episodes you are well into the tens of millions of words!

Brookside was conceived to bring real issues and real lives to the British television screen, through an ongoing drama serial. It was brave and ground-breaking. We prided ourselves on being ahead of social, political and legal issues and trends. Our audience looked to us to be challenging the boundaries of British politics through the eyes of ordinary people. We gave a voice to the genuine concerns, fears, and aspirations of our viewers – people with little or no power over their lives and their futures. Brookside was recognised from its first episode as ‘gritty social realism’, but we weren’t afraid to make people laugh along the way.

It was very important to us that we moved with the times. In the 1980s there had been a major national focus on Trade Union politics, and this was reflected in the programme. As we moved into the 1990s other social issues began to dominate, including LGBT+ issues, drug misuse, rise of feminist politics etc. Brookside further explored all these issues and many more.

So, having created hundreds of Brookside stories, it’s very hard to pick out a favourite – although the three-year-long ‘Body Under the Patio / Jordache’ story of domestic violence and child abuse is high on my list.

Maybe an easier way to frame it is to recognise that I have four favourite Brookside characters who were iconic soap characters played by outstanding actors who were great to write for: Sheila Grant, Jimmy Corkhill, Sinbad the Window Cleaner, and Mick Johnson. (Sue Johnstone, Dean Sullivan, Michael Starke, and Louis Emerick).

Each of them was a working-class character who grew in strength and influence over many years from essentially the same starting point – as one of life’s underdogs – people with no power or agency in wider society. Each of them showed great resilience, courage, and human spirit to overcome all the adversities they faced, and a political system heavily weighted against them.

Throughout your career you have often worked with the general public and young people in particular devising work together, how does this process differ from being commissioned to write a script by yourself? Can you make any suggestions for good practice in terms of this method of creativity and writing?

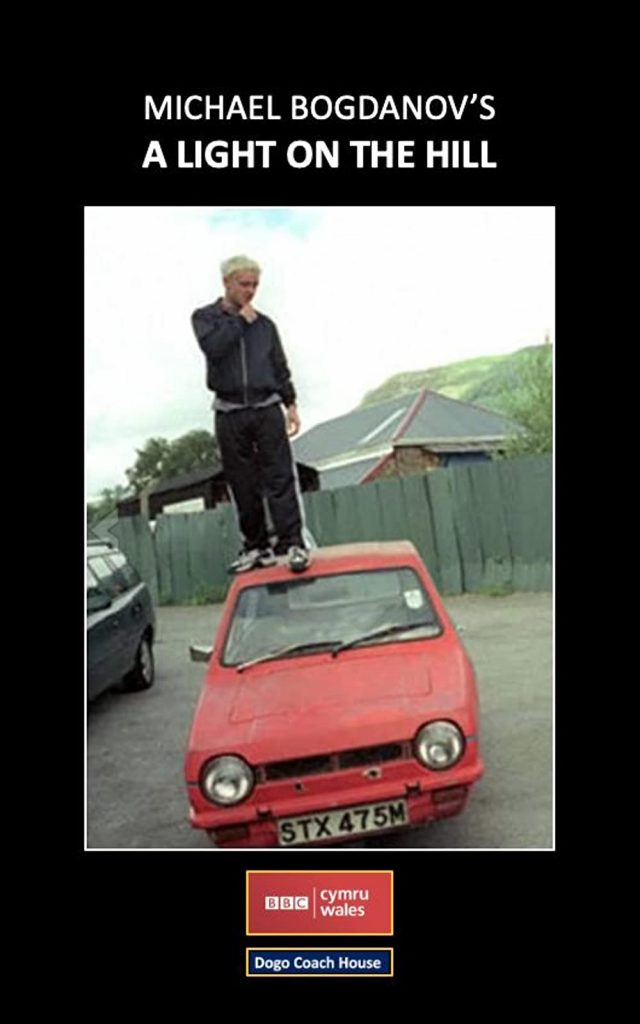

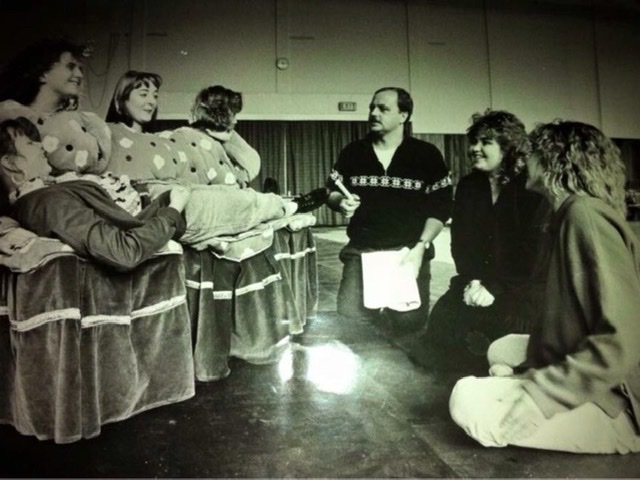

I’ve had extensive experience creating drama with communities including large-scale community plays in Wales and London, youth theatre in Belfast, youth and community film for the Rural Media Company and the BBC Wales Millennium Film, ‘A Light on The Hill’, commissioned and directed by Michael Bogdanov.

In all instances I aim to balance the process and the product equally. I always set the bar as high as possible, and ensure the whole project is delivered to the highest professional standards. This has an immense impact on the participant’s self-esteem and sense of achievement and can have a profound effect on people’s lives, including those in the audience. Best practice includes providing good access that removes barriers of all kinds, good listening and learning skills, honesty, respect, and integrity. With those basic principles in place everything else is about creating supportive systems and logistics that give people the best chance to grow in confidence and deliver at a level that they never thought they would be able to achieve.

There are a range of organisations supporting Wales based writers. I wonder if you feel the current support network and career opportunities feel ‘healthy’ to you? Is it possible to sustain a career as a writer in Wales and if not, what would help?

It’s difficult to envisage a time when it will be genuinely ‘healthy’ as demand far outstrips supply. For example, the National Theatre Wales Community has four hundred and eighty-two members in its Writers Group. Let’s say half of them are active and wanting to write plays and get them performed. That’s over two hundred writers, while the number of commissions via companies like Theatr Clwyd, NTW, Sherman etc, will come nowhere near that in any one year.

This makes sustaining a career through theatre writing extremely difficult, except perhaps for a handful of playwrights. I’ve always thought of myself as a dramatist, not just a theatre playwright. This means in practice that I’ve gone out of my way across my career to find opportunities to deploy my core skills in a wide range of performance settings – radio, TV, film, circus etc. I would estimate that probably over 90% of my career earnings have come from working outside Wales.

If you were able to fund an area of the arts what would this be and why?

My ‘wish list’ would include: a Rural Region of Culture, youth theatre, touring theatre, new writing by writers of all ages, opportunities for women playwrights, mentoring… it could go on to be a very long list!

What currently inspires you about the arts in the Wales?

I’m hugely inspired by the number of young people coming through high-quality training and their determination to find all kinds of opportunities to tell diverse stories through drama. Their belief in what they do, and their love of it clearly transcends all else. But it’s very clear that, although financial remuneration doesn’t drive theatre makers on – poor financial rewards work against theatre makers from poorer backgrounds, so we risk those voices not being heard.

What was the last really great thing that you experienced that you would like to share with our readers?

Just before COVID, I worked with Sue Parrish, Artistic Director of Sphinx Theatre Company, a long-standing collaborator. The project we created was Words as Weapons – in partnership with Tom Kuhn of the Writing Brecht Project at Oxford University, Rowan Padmore from Arts at the Old Fire Station with CRISIS, the homeless charity, in Oxford and a group of participants with lived, often current, experience of homelessness.

As part of my preparation to run a sequence of writing workshops I read nearly one thousand Brecht poems, newly translated into English by David Constantine and Professor Tom Kuhn. It was a great privilege to be given access to this work, pre-publication, and what a journey of discovery it proved to be – page after page of surprising subjects and diverse styles. I’ve always believed Brecht had a voice that speaks to our lives today, but the more poems I read the stronger this conviction became.

Our writing group would meet every Monday afternoon and I’d use some of these Brecht poems as triggers for creating new work – in whatever form each group-member wished to try; poem, lyric / song, monologue, scene etc. When we read the Brecht poems aloud and discussed them, we found that their contemporary resonance and relevance was often quite extraordinary. He wrote some of these poems one hundred years ago, but he could easily have been writing directly about today.

Brecht’s words, his weapons, proved to be a fantastic catalyst for generating some exceptional new writing. Our workshop approach encouraged and nurtured each writer’s own voice. As each member of the group grew in confidence, they found themselves liberated and they pursued their own new writing with real energy and purpose. Each of their voices became clearer and stronger. I’ve no doubt Brecht would have genuinely celebrated this spate of creativity and commentary. As they created each new piece their hunger to express themselves matured, their words demanded to be shared and their voices demanded to be heard.

When we all stepped out onstage, in our live Words as Weapons performances, the packed houses listened intently and were moved and entertained as well as intellectually stimulated and politically provoked. But at the same time, these audiences were struggling to get their bearings.

This was two worlds colliding: 1920s Berlin v Oxford 2018.

They understood that they were listening to new writing – but they also knew we were sharing some Brecht poems – and at times they found it impossible to work out who had written what and when! That was a great project on so many levels.

Thanks for your time Peter

Brilliant interview Peter and a reminder of your prolific, successful career as a writer. Very proud big sister!