Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad is one of those novels that has stuck with me for pretty much my entire life. Its content—the story, the themes and the prose—have been etched into my mind ever since reading it for the first time as a teenager, and because of this (along with its miniscule size—you could easily read it in a single afternoon) it’s a novel that I go back to time and time again.

Joseph Conrad’s legacy within the modern Western canon is clear, and need not be discussed or regurgitated at length here. But it’ll suffice to say that it would be a hard task finding any author of fiction writing in the twentieth or twenty-first centuries who doesn’t owe at least something to his work. This is remarkable considering that Conrad himself wasn’t a fluent English speaker until he reached his twenties (he was born and raised within the Russian Empire in the mid-nineteenth century and emigrated to Britain later on).

Heart of Darkness is easily Conrad’s most well known novel. This may be in part down to the popularity of the 1979 film Apocalypse Now, which serves as a loose adaptation of the novel. Actually, this film acted for me as a gateway to Heart of Darkness—I had no idea the novel even existed before watching Apocalypse Now. This really is testament to the power of Conrad’s writing, because even though Apocalypse Now takes place almost a century after the novel does, and is therefore set within entirely different historical settings, its themes still translate with near-perfect precision.

Poster for the film Apocalypse Now (1979)

From reading its very first page you get the instant impression that Heart of Darkness is written in quite a unique way. It employs a first person narrative, yet the narrator is a nameless nobody—we learn next to nothing about him throughout the course of the story. The only thing we ever really learn about the narrator is that he is an idealistic young mariner working on board a cruising yawl (the Nellie) set to depart from London. Heart of Darkness employs a frame narrative, so the purpose of the narrator is to detail the experiences of the novel’s true main character (Charles Marlow) who is telling a story of his expeditions through the Congo Free State to the mariners aboard the Nellie. The telling of this story encompasses the entirety of the novel.

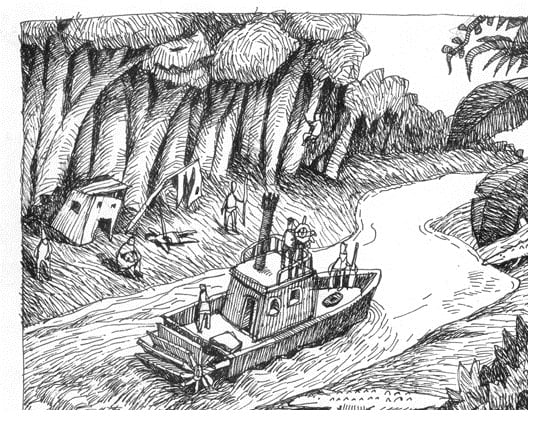

Illustration of a steamboat traveling along the Congo River

Fundamentally, Heart of Darkness is about Western colonialism, and Marlow’s story brilliantly encapsulates all the horrors associated with this movement. He recounts his journey along the Congo River within what was then a Belgian occupied territory, with the prime objective of meeting an ivory trader known as Mr. Kurtz (the novel’s antagonist). Throughout his journey, Marlow discovers that Mr. Kurtz has adopted an almost legendary status as the finest Western agent within all of the Congo. Marlow even obtains a report written by Mr. Kurtz explaining how it is the White Man’s duty to spread civilization across the imperial frontiers of Africa, and we learn at this point that this is exactly what Mr. Kurtz has tried to achieve along the Congo River. Yet upon finally meeting him near the end of the novel, we are confronted with a man who has quite literally lost his mind. He has amassed an almost religious following among the natives who venerate him as a God-like being, whilst surrounding his house are wooden palisades with decaying human heads affixed to their tops (which presumably once belonged to his former prisoners). We also learn that he has begun raiding nearby villages for ivory, creating havoc among the natives. It seems that in his effort to spread civilization into the darkness of Africa, he himself has become darker, more savage, as a result.

Illustration of Mr. Kurtz

In many ways Mr. Kurtz acts as the perfect embodiment of Western colonialism, as he asks us to consider how it’s even possible for us to civilize non-Western peoples when we are not civilized ourselves. This certainly rings true today, particularly when we think of the recent Iraq and Afghan wars, along with the ways in which we’re currently dealing with the so-called Islamic State. Yet in my experience, no two readings of Heart of Darkness are ever quite the same. The parallels drawn between Belgium’s colonization of the Congo and the Roman’s conquest of the Thames, for example, are there perhaps to reminds us that colonialism represents an all-pervading aspect of the reality within which we live, and has played a major role in shaping humanity’s history. The fictionalised setting within the Congo, on the other hand, may also be seen as a playground in which moral virtues evaporate and where those who are most hungry for power come out on top. Indeed, it’s the moral standoffishness with which this novel was written that means it avoids being interpreted in any singular way. Rather, it forces you to think for yourself.

Despite its tiny size, Heart of Darkness is a dense and richly textured novel which makes use of some excellent prose and symbolic undertones. It really is a fantastic novel, and definitely worth a read.

by Rhys Morgan