(4 / 5) Whistler’s Woman in White: Joanna Hiffernan

(4 / 5) Whistler’s Woman in White: Joanna Hiffernan

(4 / 5) Kyōsai: The Israel Goldman Collection

(4 / 5) Kyōsai: The Israel Goldman Collection

A final gallery trip would be an action packed afternoon at the Royal Academy. In Whistler’s Woman in White show, we get a telling scope on Joanna Hiffernan, Irish model and muse to many an artist of her time. The show features her in many frames and other women in white from the era, Willkie Collin’s book of the same name getting referenced and a poster print from a staging looms over most viewers. A Klimt painting remains a thing of beauty, though we crave his more exuberant gold pieces. Rossetti’s painting of The Annunciation is one of the finest work here, of a slim build, the biblical image compress to a narrow canvass of tension. Truly something to marvel at.

Perhaps most fascinating is Joanna in Gustave Courbet’s Jo, the Irish Woman. Most remarkable, there are three version of the very same painting and it remains unclear which is the original. How fascinating to pick up on the slight variations in each of them, her eyes more sunken in one, her cheeks more rouge in another. It’s quite a candid work and it remained a highlight. Courbet’s Seascapes on the other hand felt quite pedestrian and of little interest, I spent a very short amount of time with them.

Of course, it all lead up to the big guns. Whistler’s Woman in White was the dazzling finale to this mostly fine exhibit. Joanna glows here, her red hair almost veil like with strangely little detail in it. As if a bride, she holds a flower and is atop a wolf skin rug. This is a moving encounter, Whilst proving his mastery though other work in the show would also prove this. She looks beyond the viewer as if lost in another realm, adding to the dreamy quality of the whole encounter. I can’t gush enough about this painting. Though quite a small exhibit, it’s effect is monumental.

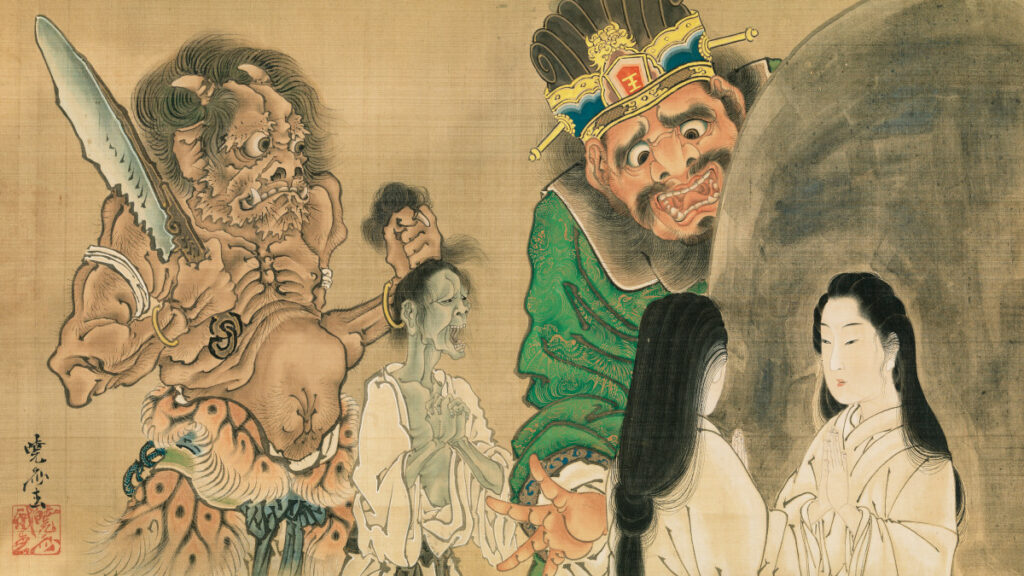

Following on was something drastically different. Kawanabe Kyōsai’s work from Japan makes for a highly amusing and often touching apparition. It’s the ink work that really makes it. Some of the fine folklore and depictions of animals stand out. A female ghost is a horrible sight on one screen, a shocking sight in keeping with the superstition of his home country. The West adored his work and it’s easy to see why. Even just a cat with such a look of contentment makes for a joy to gaze upon. Some of the more outrageous drawings involves the bottoms and testicles of the figures, the latter being affronted by another more curious cat. You could almost hear the slide whistle.

The detailing on the robes of some women in the art is another eye watering detail. Also noteworthy how some of the crow works are highly figurative, the ink generously spread around, yet still it is clearly a crow. It’s the beak that gives it away, as well as the obvious black ink usage. A giant wide-spread panel sees demons and creatures, looking as if it was created yesterday, such was it’s fine quality (Gerald Scarf would lap it up!). This has clearly been well looked after (dating from 1871-1889. This would clearly go on to influence manga and anime, staples of Japanese culture today. Another fine show, for another fine artist.

At the Royal Academy of Arts, Whistler’s Woman in White: Joanna Hiffernan continues till 22 May 2022 and Kyōsai: The Israel Goldman Collection till 19 June 2022.

(5 / 5)

(5 / 5)

(3 / 5)

(3 / 5)