(5 / 5)

(5 / 5)

Having been a fan of Stephen Adly Guirgis’ The Last Days of Judas Iscariot (hereafter Last Days), I was eager to check out his similarly incendiary-of-title follow-up ‘The Motherf**ker with the Hat’ (hereafter That Mo-Fo Show). Directed by Andy Arnold, this collaboration between Sherman Theatre and Tron Theatre, Glasgow is ninety minutes of electric drama, with no interval to slow down the break-neck pace of this magnificent masterpiece unfolding on the stage.

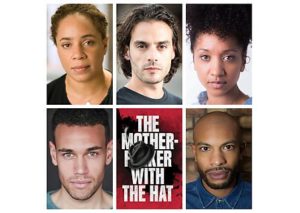

Set in the grimy grit of Hell’s Kitchen NYC, The Mo-Fo Show follows a young man named Jackie, a newly-released ex-con recently home from prison, as he tries to stay clean and out of trouble despite personal revelations that threaten to turn his world upside down. Francois Pandolfo plays Jackie with such roguish, ramshackle appeal that you understand why Veronica, Ralph and Julio still care about him despite his transgressions. He’s a lovable loser; a user in all senses of the word. As Satan tells the lawyer El-Fayoumy in Last Days, ‘you’ll never be loved, because you’re incapable of it’, which sums up one of Jackie’s myriad issues to a tee. Unendingly selfish and mercurial, Jackie cares little about the thoughts and feelings of others as long as they serve his purpose. But by the final curtain, there’s hope – if ambiguously framed – that Jackie may finally have a toe on the path to recovery; though he leaves threats in his wake, a revenant of his presence that lingers uneasily after the curtain falls.

Despite this being ostensibly Jackie’s story, we start and end the play with Veronica, masterfully played by Alexandria Riley, who is fast proving herself as one of the most dynamic actors currently treading the boards. To me, Veronica is the most tragic character of them all, because she learns nothing, and is doomed to re-enter the vicious cycle in which she has imprisoned herself. When the play starts, Veronica is chastising her mother on the phone for dating a deadbeat and taking drugs; and yet she casually snorts coke during the conversation, and then praises her own deadbeat boyfriend for finally getting a job. Veronica is her mother’s double, repeating the same harmful mistakes of the past again and again. We leave her at the end alone in the dark, with little hope for the future.

Veronica projects an image of brutal honesty, but it conceals secrets and lies – though she is far from being the only hypocrite in the play. Jackie protests that he is a good man, but it masks the fact that he is not. Ralph presents an image of being the ideal man, but in reality he is far from perfection. Played with mesmerising charm by Jermaine Dominique, Ralph’s shocking switch from wise everyman to shrewd manipulator is subtly portrayed and all the more sinister for it. Having said that, none of the characters are moustache-twirling villains, although they say and do bad things, making each character’s own personal Dark Passenger frighteningly realistic.

Each character leaves the play with their own long list of regrets – for the life they could have led, for the people they could have been, for the choices they’d have made differently if they had the chance. Regret makes a double of you, leaving an imprint of who you might have been if not for one choice, one moment, one mistake. The character of Victoria – wonderfully, woundedly portrayed by Renee Williams – exemplifies this duality most keenly of all. Her choice to follow love over career has left her hollow and achingly lonely, so much so that she wants to ‘disappear’, if only for a while. She is the least hypocritical character, except perhaps for Jackie’s Cousin Julio.

Julio may just be the most well-adjusted character of the bunch, a guy who both enthusiastically enjoys the minutiae of cooking and also occasionally puts people in the hospital. He even names his violent alter ego, referring to it as Jean-Claude Van Damme. Though perhaps the most dichotomous character of the cast, Julio is engaging precisely because he accepts that he is a bad man – a clear foil for Jackie, who proclaims to be a good man but is, in truth, the oppsite. Kyle Lima frequently treads a fine line between pastiche and plausibility in the role, but wonderfully crafts a performance which feels both fantastical and naturalistic, and the kind of person you would legitimately enjoy hanging out with in real life. Julio is a potent mixture of Pulp Fiction’s Jules Winnfield, The Birdcage’s Agador Spartacus, and Yoda from Star Wars; and if that sentence alone doesn’t convince you to see the play for yourself, I don’t know what will.

In addition to being a rapt audience member, I also had the pleasure of being a speaker on the post-show panel, led by Tim Howe, the Sherman’s Communities and Engagement Coordinator, and my fellow panellists Luke Hereford (the play’s assistant director), and Nick Shepley (addictions therapist at The Living Room). The discussion was lively and engaging as always, with some great insights from the panel and the audience alike.

Every character in the play was, or had been, an addict – to drugs, alcohol, sex, sometimes a combination of those things. But they’re also (quoting Last Days) ‘addicted to tragedy and punishment’, doomed to wallow in a hell of their own making; a vicious circle of self-imprisonment. Secrets and lies have stretched taut to breaking point between the characters; revelations take time to crack open, but once the lid is lifted on that particular Pandora’s Box, a whole swathe of sorrows and deceits come pouring out, with little sign of stopping. Some of the revelations were so shocking that I gasped audibly when reading them for the first time, and still felt the aftershocks of that surprise whilst watching the play live. Each character fails to stave off the throes of their own addiction – often, as Nick observed, just swapping one addiction for another.

The play is so rich and rewarding that there were so many observations, thoughts and ideas that there simply wasn’t time to discuss on the panel. On reading the play for the first time, the appearance of the hat, sans owner, seemed almost to be mystical, even mythic, in nature. It appears without warning, like an omen, and is the MacGuffin which ignites the dramatic spark which burns throughout the rest of the play. And when Jackie goes downstairs to confront who he thinks is its owner, it seemed almost as if he was descending into the pits of hell for an audience with the devil. Much like Godot, the eponymous hatted individual is absent from the proceedings, and yet his spectral presence haunts every scene. Or, rather, the mo-fo with the hat does appear, though not in the guise Jackie first expected. Whether its magical or mundane, the hat acts as a manifestation of mistrust and misdemeanours – Jackie initially likens it to the mark of Zorro, sign of the titular mo-fo marking his territory. He closes the play, and the narrative loop, by leaving his own mark behind – a Commodores CD, a relic of his long-held love for Veronica, now a monument of a bygone era.

This is not a courtroom drama, despite a number of legal elements splintered through the story. I lost count of how many times assault and battery occurred, both with and without a deadly weapon, not to mention the copious references to drug use, convicted and otherwise. Jackie has a very particularly twisted moral code – when he first suspects Veronica of having an affair, with scant evidence to go on, he argues that murder would be ‘f**ked up but understandable’ in the circumstances. Jackie is every person’s judge but his own. The play reinforces Guirgis’ own words from Last Days, in which the lawyer Fabiana Aziza Cunningham proclaims that ‘those who need forgiveness are the ones who don’t deserve it’. But, as Last Days attests to, ‘you have to participate in your own salvation’. Jackie ends up serving time, not for his various assaults, batteries and criminal threats, but for breaking parole. The law is a distant, vaguely drawn entity in the play; but it is an interesting consideration of how a person’s internal self differs from their external persona, and how, as Jackie observes, ‘people can be more than one thing’.

Vibrant, vulgar and viciously insightful, The Motherf**ker with the Hat is an unrelenting, rewarding play that lingers in the mind long after the final curtain. Incendiary, inventive and intoxicating, the play showcases the second-to-none cast and brings the wildly exhilarating worlds of Stephen Adly Guirgis to sharp, relatable relief. Utterly unmissable. And following on from that, I would also highly recommend Guirgis’ The Last Days of Judas Iscariot, as a companion piece to this play, as its predecessor, or as a stand-alone study of the prisons we make for ourselves.

Barbara Hughes-Moore

One thought on “Review The Motherf**ker with the Hat, Sherman Theatre by Barbara Hughes-Moore”

-

Pingback: End of Year Update & 2019 Plans – The Law Lass

Get The Chance has a firm but friendly comments policy.