If you want to get an inkling of what contemporary dance is, you need to watch dancers not dancing. Ahead of a run, Rehearsal Director Pablo Sansalvador-Chambers asks dancers of National Dance Company Wales (NDCWales) to ‘space it,’ go through the movements to check where they are meant to be. The movements are only sketched. No need for focus. Tim Volleman, a dancer with NDCWales, scratches his newly grown beard and jokes making funny moves that are extraneous to the piece in front of Elena, another NDCWales dancer. They are not meant to dance, only to go through the moves. There is no acting, no presence, no intensity. Then the run begins. I watch and feel their muscles tensing up and contracting, their body stretching and twisting. That power, swiftness, energy I’ve come to recognise in contemporary pieces is back.

Contemporary dance has a strange quality to it. It doesn’t go for the graceful lightness of ballet, for clearly laid out patterns, for established and precise movements. It has a spontaneous quality, but it is not carefree; it is intense. ‘I think contemporary dance can get very serious,’ Aisha Naamani, one of the NDCWales dancers tells me. It is so serious that dancers need some comic relief at times, after a hard phrase or when they get things wrong. They do so by playing ballet. Ballet, that invisible ‘other,’ that parent who is always in the room and yet belongs to another space. It often creeps in as an aside, something that doesn’t belong and yet is part of one’s core identity. When it gets too tense, dancers ‘play ballerinas’ and release the tension.

All dancers of NDCWales have had some training in ballet; yet as they begin the ballet class led by Pablo, they blush and feel awkward. ‘If you mess your pirouette, everybody sees it,’ says Nikita Goile, dancer and choreographer of the piece Écrit, part of the Roots production now touring Wales. They do indeed. Unlike most piece rehearsals, Pablo begins the ballet class by drawing back the curtains and revealing the mirror. The class begins with gentle movement to slow piano music. It is not classical music but pop music in a piano version. This time, the ‘escape’ from the intense focus required by the ballet class is found in extraneous movements that are not ballet. Some dancers release the tensions by doing some martial arts or street dance, and blushing. As the music gets faster, the movements get faster, as the music gets more recognisable, the dancers sing. Some move to the rhythm of the music as a preparatory preamble to get into the required ballet movement.

Ballet is ‘healthy, nutritious,’ says Tim, ‘it is structured, it gives you a good base, a rule. To be able to break the rule, you need to know what the rule is.’ Contemporary dance takes the established rule, the customary view, the narrative structure and subverts them. It wants you to see with new eyes. As Aisha explains, an element of contemporary dance is to ‘try to think of ideas differently, or explore different ways around a common thought, whatever that might be. Someone once said to me contemporary dance is this big umbrella, movement that doesn’t necessarily have a story all the time, it’s more about an experience and your interpretation of it.’

Contemporary dance can be very conceptual, sometimes too conceptual and abstract. I have heard dancers often complain about it. The NDCWales production Roots seeks to be accessible and engaging.

The piece Rygbi Annwyl / Dear by NDCWales Artistic Director Fearghus Ó Conchúir, expresses the mutual reliance, joy, and disappointment of the national sport; Anthony Matsena’s Codi speaks of the community spirit of the Welsh valleys; Nikita Goile’s Écrit is about the flows of personal relationships; Ed Myhill’s Why Are People Clapping? captures the playfulness of sport and dance.

Common to all the pieces is an energetic quality of movement. Energy is often mentioned. Aisha tells me, ‘You can have the same angle of an arm but how you get the arm to that place is going to have a different energy.’ She pauses and then continues, ‘I think it comes down to quality and what kind of, to put it with an image, if someone moves their hand, they’re pushing water or something heavy that gives a different quality and energy than moving through air. Quality creates different energy in the room.’

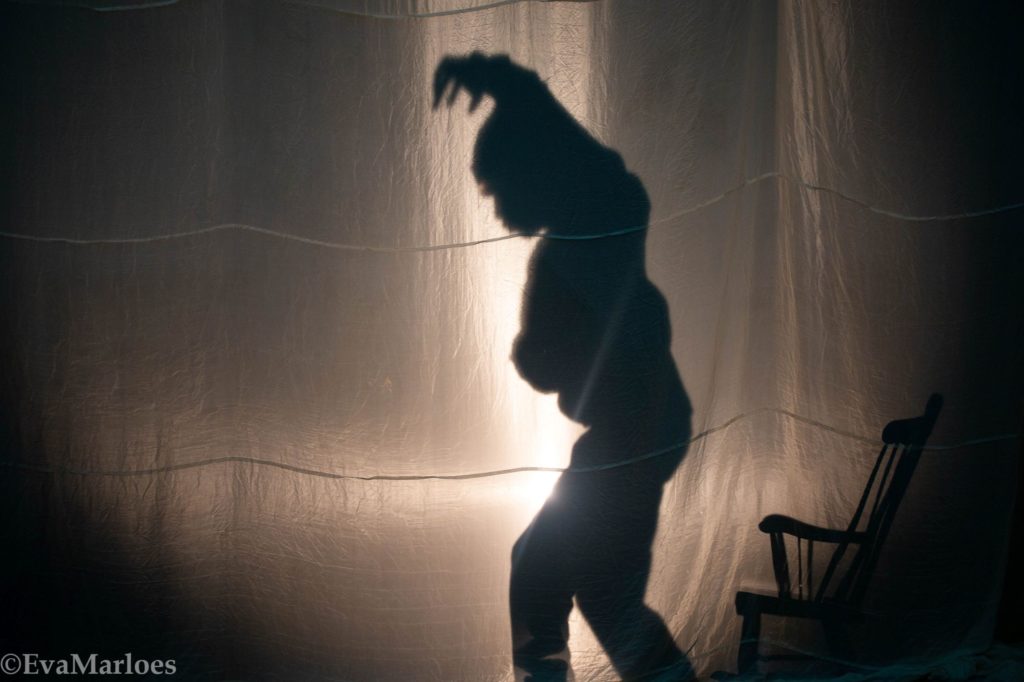

‘There are problems with contemporary dance,’ Pablo says, ‘the public come out and don’t understand anything or they don’t know why it was like that.’ The danger of abstraction and obscure symbolism lurks behind contemporary dance creations; yet there is something mesmerising about contemporary dance. For Pablo it’s ‘the realness, the physicality without the illusion that it’s pretty or untouchable. Classical ballet has to be flawless and exquisite. Contemporary dance can be all that but it is more organic.’ Contemporary dance seems to draw out life from dancers. The effort, pain, and intense emotion of it are laid bare for all to see. It is raw and unreservedly human.

(This article is based on

Eva Marloes’ interviews with Aisha Naamani and Pablo

Sansalvador-Chambers as well as the observation of NDCWales rehearsals of Roots)

Roots opens today at Theatr Clwyd in Mold.

Mold Theatr Clwyd Thursday 7 November 2019, 19:45 BOOK

Friday 8 November 2019, 19:45 BOOK

Cardiff Dance House Tuesday 12 November 2019, 19:30 BOOK

Wednesday 13 November 2019, 13:00 BOOK

Wednesday 13 November 2019, 19:30 BOOK

Thursday 14 November 2019, 19:30 BOOK

Blackwood Miners Institute Tuesday 19 November 2019, 19:30 BOOK

Ystradgynlais, The Welfare Thursday 21 November 2019, 19:30 BOOK

Narberth, The Queens Hall Friday 22 November 2019, 19:30 BOOK

Aberdyfi, Neuadd Dyfi Sunday 24 November 2019, 19:30 BOOK

Caernarfon, Galeri Tuesday 26 November 2019, 19:30 BOOK

Pwllheli, Neuadd Dwyfor Wednesday 27 November 2019, 19:30BOOK