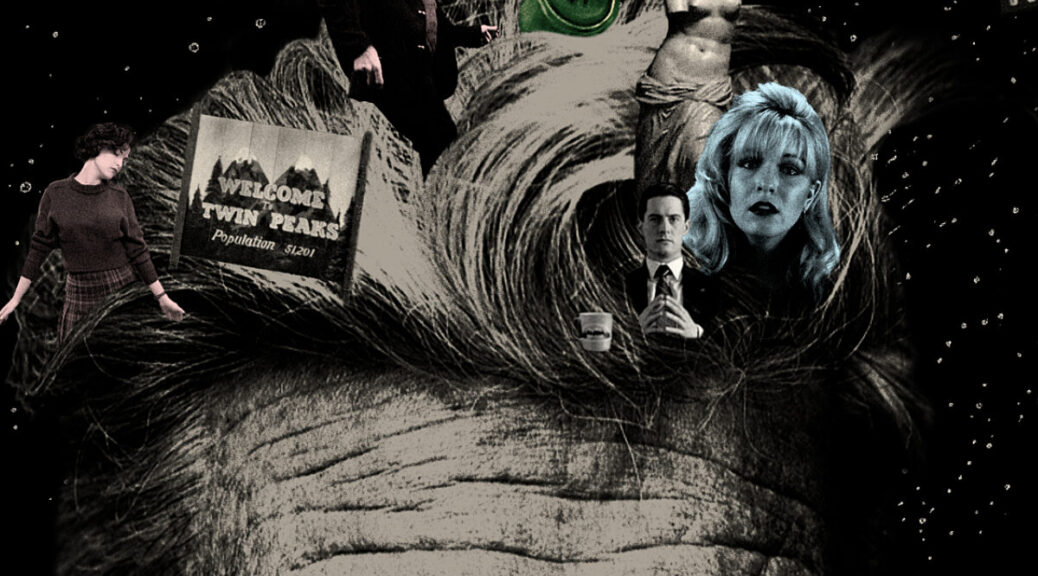

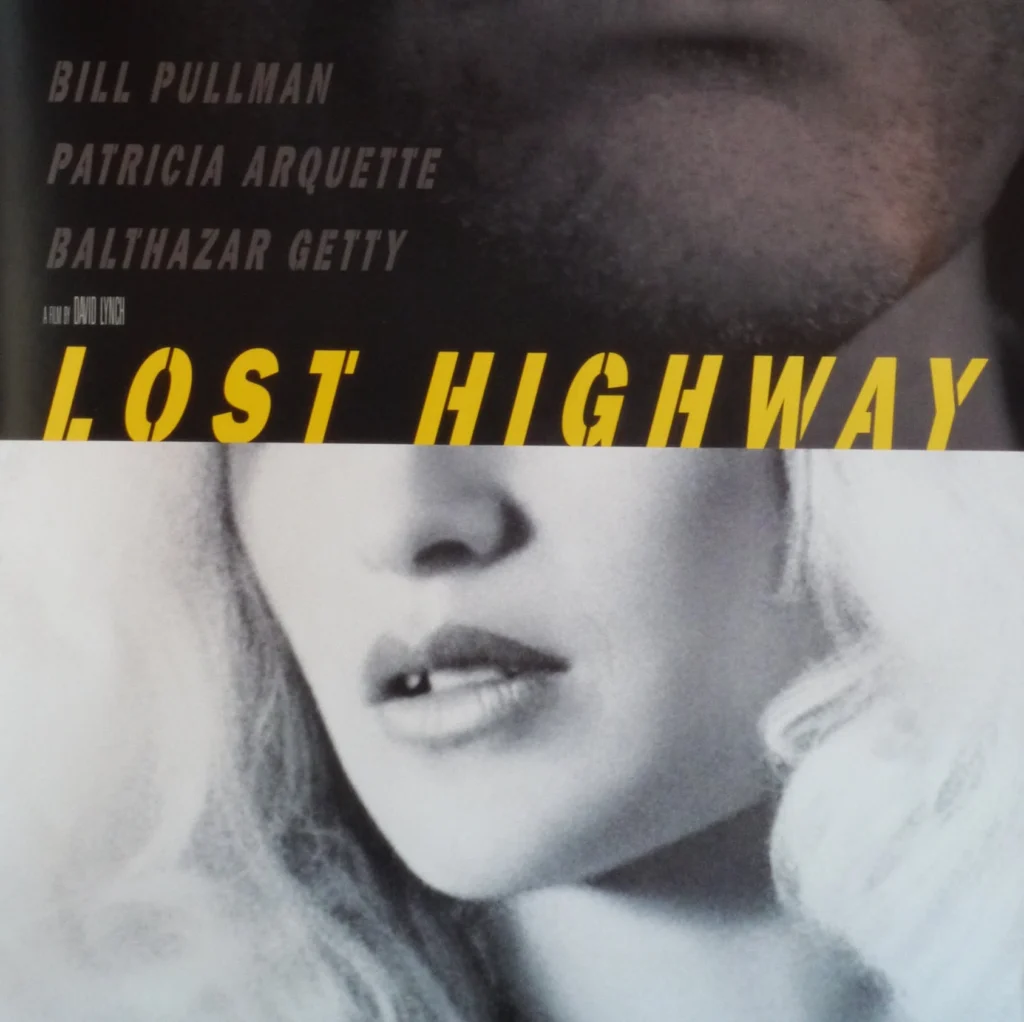

With Chapter’s David Lynch season recently concluded, I wanted to reflect on some of the films I watched. As a film fan, Lynch has always loomed large. I’d seen and been delightfully confounded by Blue Velvet (1986) at a young age and had tepidly dipped my toe into the uncanny waters of Twin Peaks (1990-91). In the wake of his death, I, like many others, decided to dig further into his work and Chapter’s season provided the perfect opportunity.

Over the course of the season, it became clear to me that Lynch’s filmography has long been preoccupied with fragmentation. I’ve always been drawn to the theme- the way identity, perception, and experience can splinter and overlap- and in Lynch’s work, this fascination felt amplified. Watching him wrestle with fractured subjectivity made the films feel both unsettling and alive, and it’s this tension that kept pulling me deeper into his worlds. In Lost Highway (1997), Mulholland Drive (2001), and Inland Empire (2006) specifically, this fascination takes a distinct trajectory: what begins as fragmentation as a symptom ultimately culminates in fragmentation as a condition.

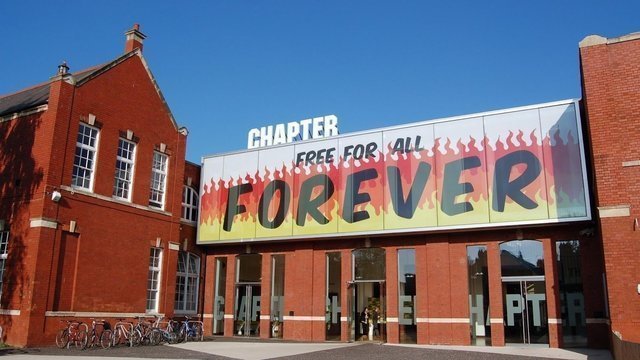

Lost Highway: Fragmentation as Escape

Lost Highway begins with the paranoia of being watched. Fred Madison (Bill Pullman), a jazz musician, receives videotapes filmed inside his own house. The tapes arrive anonymously, and are terrifying because they suggest an external, spectral eye. His subjectivity unravels under this pressure. His sexual inadequacy, jealousy, and inability to communicate are compounded by guilt- likely for murdering his wife, Renee (Patricia Arquette). “I like to remember things my own way,” he says early on, insisting on control over memory. It’s a fragile defense. Soon, his psyche generates an escape route: Fred becomes Pete Dayton (Balthazar Getty), a younger man who is confident, desired, potent.

This transformation, which Lynch called a “psychogenic fugue,” is part plot twist part psychic rupture. Pete offers Fred a way to continue for a while, to live inside a fantasy of vitality. But fantasies cannot hold forever. The recursive line “Dick Laurent is dead” becomes both the spark and the implosion of this psychic construction. Fred is caught in a Möbius strip: both the man receiving the message and the man delivering it. The loop closes, and the fantasy collapses.

Fragmentation in Lost Highway is thus a symptom; a psychic defense against guilt and impotence, a way of buying time in the face of trauma. The self fragments because it cannot endure.

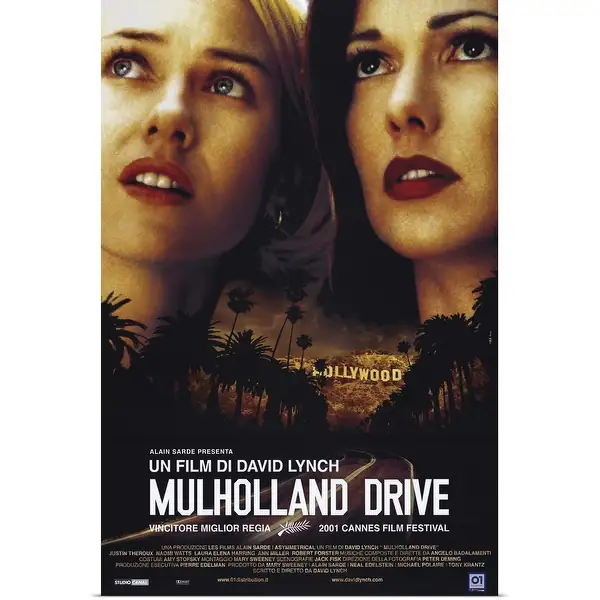

Mulholland Drive: Fragmentation as Dream Logic

If Lost Highway uses fragmentation to repress trauma, Mulholland Drive structures it around dream logic. The first half of the film plays like a fairy tale: Betty (Naomi Watts), bright-eyed, bushy-tailed and gifted, arrives in Los Angeles full of promise. She discovers Rita (Laura Harring), an amnesiac brunette, and together they set out to solve a mystery.

For a while the fantasy works, and Lynch treats it with deep reverence. Hollywood glows with potential. But eventually the frame cracks. Betty becomes Diane, Rita becomes Camilla, and the romance collapses into betrayal and humiliation. The fantasy was Diane’s dream, a desperate attempt to rewrite her failures and rejections. In this structure, fragmentation serves as a hinge: dream versus reality, fantasy versus trauma.

Diane’s tragedy is not that the fantasy was false, it was real enough to genuinely sustain her for a time, but that it could not hold. The kiss between Betty and Rita embodies this tension. It’s tender, charged, but ultimately folded into the dream logic that unravels into despair. The recognition it offers cannot last. Like Lost Highway, fragmentation here derives from something and feels narratively coded; in the dream context, the doubling makes sense. However, in Mulholland Drive the dream world is less a cover, and more a lived space, vivid and real, almost equal to the ‘reality’ that follows it.

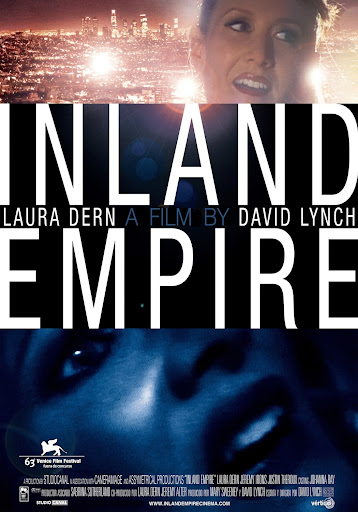

Inland Empire: Fragmentation as a Way of Being

By the time we reach Inland Empire, the logic develops considerably. Nikki Grace (Laura Dern), an actress cast in a mysterious film, becomes Sue, a character within that film. But from the beginning, the boundaries are porous. Nikki bleeds into Sue, Sue into Nikki. Other figures emerge: the Lost Girl watching from a room, the prostitutes, the rabbits in a sitcom-like set, a Polish woman, various doubles. Identities multiply, overlap, and dissolve.

Unlike Lost Highway or Mulholland Drive, there is no clean binary. There is no dream to wake from, no fantasy to collapse. There isn’t even a single doubling. Multiplicity proliferates without axis. Nikki/Sue doesn’t fracture because of an identifiable trauma; she was never whole. She is always already multiple: actress, wife, prostitute, ghost, watcher, watched, victim, comforter.

Shot on digital video, the film’s grain and distortion are inseparable from its content. The camera is no longer an outsider intruding, as in Lost Highway. Nor is it the machinery of fantasy, as in Mulholland Drive. In Inland Empire, the camera is reality itself. It shapes the very condition of subjectivity, especially in the modern age, where Lynch seems especially prescient: to be filmed, to be seen, to perform endlessly.

Unlike the other two films, fragmentation in Inland Empire doesn’t seem to stem from anything; it’s not a symptom, or a narrative device- it’s a state of being and doesn’t necessarily lead to revelation. Nikki/Sue fragments not to withhold truth or conceal trauma but because, in her world, that’s what the self does. And then there’s the kiss. Unlike the Mulholland kiss, this one is not eroticised or doomed. It arrives as a recognition: one woman truly seeing another, outside the mediation of roles and screens. Multiplicity doesn’t disappear, but for an instant, it coheres into recognition. It’s not a cure, or a return to unity, but an instant that acknowledges fragmentation and continues regardless.

Watching Inland Empire last of the three films felt appropriate. Not just because it was Lynch’s last feature film, or his longest, or arguably most difficult- but because it feels like the culmination of a journey. Where can you go after rejecting not just narrative resolution but fragmentation as a means to an end? The earlier films still hold out for the possibility of wholeness, even if only in fantasy, even if only for a moment. By contrast, Inland Empire makes peace with fragmentation as the default; suggesting that the self is never whole, never singular, never ‘off-camera’. And yet, the film doesn’t grieve this. If anything, its final moments are joyous: smiles, dancing, a room full of women and doubles and ghosts simply being. This notion struck me then, as it does now, as radical, deeply honest and profoundly moving: the subject may not unify but she does endure.