(5 / 5)

(5 / 5)

The WNO’s production of Death in Venice by Benjamin Britten is a symphony in black and white with minimal staging, effective choreography, and powerful singing. It’s a beautiful and haunting painting that conveys the internal anguish of the protagonist at the core of Britten’s extraordinary music.

Death in Venice is based on the novella by Thomas Mann, where Gustav von Aschenbach is a famous author who travels to Venice to find inspiration. There, he develops an attraction for an adolescent boy, Tadzio. Disciplined and ascetic in character, Aschenbach is torn between his sensual desire and his detached reason. As his attraction becomes an obsession, Venice is taken over by cholera. His passion makes leaving impossible. A glance from Tadzio makes Aschenbach rise from his chair only to collapse and die.

Aschenbach’s travel to Venice is as internal as it is physical. The initial confusion of the mind that makes him unable to write is lifted at the sight of Tadzio, whom Aschenbach sees as the embodiment of ancient Greek beauty. Yet, the aesthetic appreciation quickly plunges Aschenbach into an internal conflict between his rational mind and his passion for the boy.

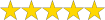

Mark le Brocq as Gustav von Aschenbach. Photo credit Johan Persson.

Olivia Fuchs, who directs this production, weaves together the different elements of music, video, acrobatics, costumes, and song with great efficacy. A black and white video is projected onto the background. It alternates depictions of the sea, at times choppy and at times smooth, Venice almost as a shadow, and Tadzio up close. The most intense moment is when Aschenbach, played by a wonderful Mark Le Brocq, is alone and the scene has nothing but a picture of Tadzio. Throughout the opera, Le Brocq excels in intensity and harrowing beauty.

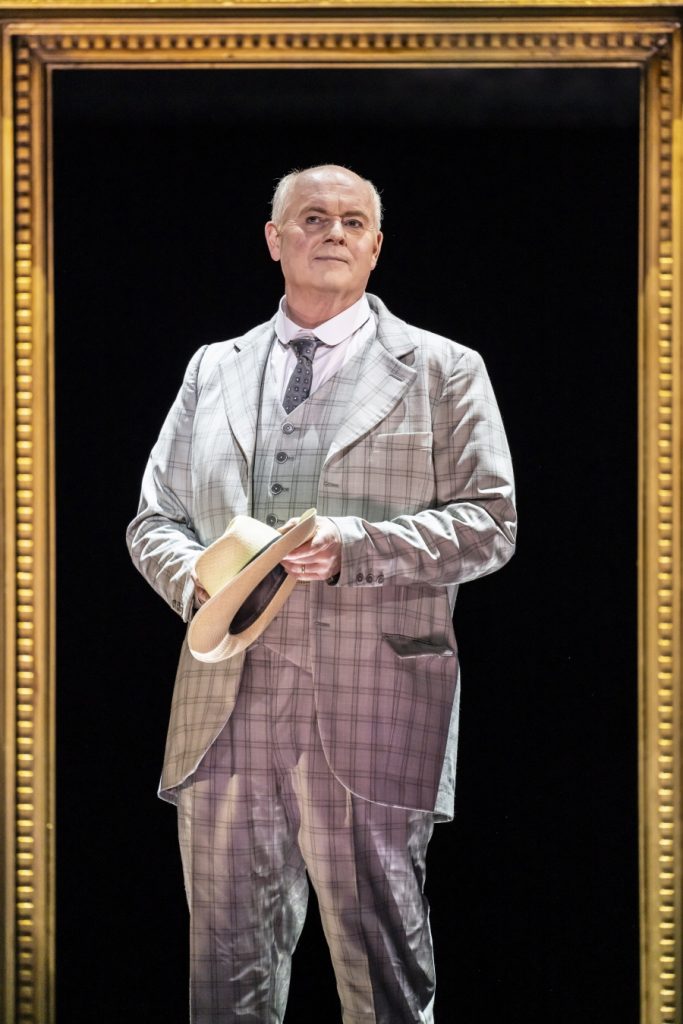

Alexander Chance as The Voice of Apollo, Mark le Brocq as Gustav von Aschenbach, and Roderick Williams as The Voice of Dionysus. Photo credit Johan Persson.

Aschenbach’s internal anguish mirrors the Nietzschean theme of the conflict between Apollo, god of reason, and Dionysus, god of passion. The battle between Apollo and Dionysus unfolds musically in the contrast between the countertenor voice of Alexander Chance as Apollo and the deep baritone voice of Roderick Williams as Dionusus. This is heightened by the juxtaposition of Apollo, dressed in a golden suit, and Dionysus, in a red suit, against the black and white background of the chorus, dressed in white when playing the hotel guests, and in black as Venetians.

Baritone Roderick Williams and countertenor Alexander Chance are equally enthralling. Tadzio has no voice; rather he embodies beauty through movement to a percussion music which Britten developed drawing on Balinese gamelan. The choice of sensual acrobatics performed beautifully by Anthony César of NoFit State Circus, directed by Firenza Guidi, conveys powerfully the Greek idea of beauty. The homoerotic acrobatic duel between Tadzio and another boy, performed by Riccardo Frederico Saggese, is allusive yet restrained. The result is mesmerising.

On a minor note, the production could have made better use of light design to emphasise Aschenbach’s internal turmoil. Overall, it is one of the best productions the WNO has given us.

Antony César as Tadzio, Riccardo Frederico Saggese as Jaschiu, and the cast of Death in Venice. Photo credit Johann Persson.

I’m afraid I can’t agree with your review. The constant repetitive use of circus performers, dominating front of stage as they do, on numerous occasions, dominates the performance. This only shifts Brittens music to the margins.

The use of the hula- hoops in the first act was the final straw for me. This work stands on its own merits, it doesn’t need gimmicks to make it interesting.

I think this must be a “Marmite” production as I loved it! I saw the original production at Snape and, to be honest, it was visually a bit dull. Having said that, my memory of its colour palette is that it was similarly monochrome: quite a lot felt familiar although memory fades after 50 years!