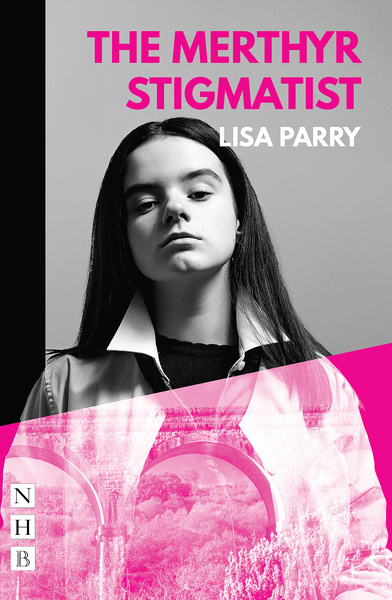

“Do I literally have to bleed in front of you to get you to listen?” This is the question that haunts Lisa Parry’s visceral new play. Co-produced by the Sherman Theatre and Theatre Uncut, The Merthyr Stigmatist is a lean, lacerating two-hander that tells the story of sixteen-year-old Carys (Bethan McLean, in her professional debut) who claims to have received the wounds of Christ. Meanwhile, her sceptical teacher, Siân (Bethan Mary-James), struggles to believe that the hand of divinity has alighted, of all places, on Merthyr Tydfil.

It’s hard to express just how incredible it is to have the Sherman Theatre back. They’ve kept the artistic flame burning through unprecedented circumstances, and their latest production is a blazing triumph of personal and epic proportions. Parry’s play nimbly traverses the rocky terrain of politics, culture, and faith, and director Emma Callander, marking the tenth anniversary of Theatre Uncut’s founding, brilliantly balances tension and emotional tautness as the play moves pacily through beat after enthralling beat.

McLean and Mary-James are not merely mirrors, personalities bleeding in between the cracks; they are each other’s prism. To bring more characters to the stage would have refracted the light these two blistering performers throw on each other. (Aptly, the patriarchal (God)head Mr Williams remains unseen and offstage). As the power dynamics shift they prowl around Elin Steele’s sinisterly symmetrical set, which variously evokes a classroom, a cage, and a confessional. Bordered by liminal space, and brought to pulsing life by Andy Pike’s vivifying lighting, the only signifiers of the outside world are the choruses of Carys’ disciples and a line of what looks like rocks, perhaps Welsh slate, lining the front of the stage. At first glance, it looked like kindling for a martyr’s pyre – but on further reflection, I detected littered scraps of the Valleys’ industrial past, and it called to mind the Welsh towns that were flooded to provide English regions with water: Tryweryn and Elan, Llanwyddyn and Claerwen. Each one an Atlantis. The ruins of these stolen cities can sometimes be seen on warm days.

Intergenerational Welsh trauma is a wound that runs deep in the show. The spectre of Aberfan is invoked more than once, and Carys chastises her teacher for leaving her hometown (and accent) behind for pastures new in Cardiff, which might as well be ‘a different world’. In comparison to the vibrant, distinct Valleys community ‘where we look after each other’, Cardiff is ‘somewhere that could be anywhere’, a metropolis in the mould of many before it. While potrayals of the Valleys have historically honed in on negative stereotypes, Parry’s play is a moving paean to Merthyr and its individuality, its beauty and its love, its humour and its character, and above all its sense of community.

Merthyr Tydfil, or ‘Tydfil the Martyr’, is named after the daughter of an ancient Welsh King, who was known for her compassion and healing skill. Her sister formed a religious community in what is now Aberfan – a vivid reminder that we are never far away from our saints. Tydfil did not run when Picts invaded her land: she knelt calmly and prayed. Parry’s play is very much in the spirit of its martyred namesake. You cannot heal a wound, or a town, by running from it. Ivan Illich described the stigmata as an ‘individual embodiment of… contemplated pain’, and Carys, like her peers and the generations to come, will have to bear the marks of damage wrought by their forebears. But, like the diamonds in Carys’ mock science exam, like the gems of the coalfields and of the pits, something special and beautiful can be formed under immense heat and pressure. You just have to know where to look.

Recorded live during the pandemic and available to stream online through to 12th June, The Merthyr Stigmatist is just under an hour of utterly transcendent theatre. It unflinchingly addresses mental health, rape culture, and self-harm, and makes space for women’s rage. The show itself is an open wound, presented to us, palms up, asking for supplication, or succour, or simply to be seen. Are the holes in Carys’ hands and feet the marks of divinity, or of delusion? That is a question for you to answer, but in doing so, you might risk missing the miracle entirely.

Get the Chance supports volunteer critics like Barbara to access a world of cultural provision. We receive no ongoing, external funding. If you can support our work please donate here thanks.