To exist, socially, at this moment in time, we have to live online, disembodied and digitized, encased within the four corners of a Zoom call. Siloed away, with nowhere to go and no-one to see, it’s unsurprising that we’ve looked to social media as a sanctuary; a digital lifeboat in a shared storm. But while it might give the illusion of solidarity, it can also make you feel the most alone you’ve ever felt in your life, and the gulf between the digital self and the ‘real’ grows wider with every like, comment, and subscribe.

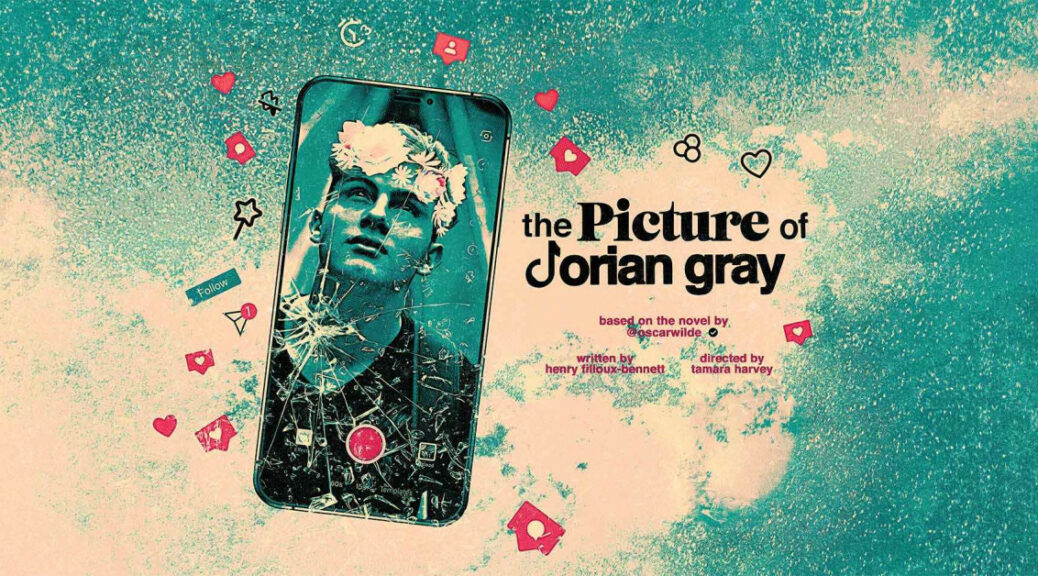

It’s a duality that Theatr Clwyd’s clever and inventive adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray revels in. Directed by Tamara Harvey and written by Henry Filloux-Bennett, this online play is an ambitious co-production between Theatr Clwyd, Barn Theatre, Lawrence Batley Theatre, New Wolsey Theatre and Oxford Playhouse, and features a star-studded cast including Russell Tovey, Alfred Enoch, Joanna Lumley and Stephen Fry (whose very appearance is something of an easter egg).

Not only does this version update Dorian Gray for the Instagram age, it sets most of the action in 2020 when its characters (and cast), like the rest of us, were in self-isolation. Sleekly made and brilliantly performed, it plays out in a series of FaceTimes, YouTube videos, Insta Stories, and interviews with the surviving characters. It’s an incredibly involving piece in the same vein as other internet-set mysteries like Catfish, Searching, and Unfriended, but with the kind of quality that you only find in a truly excellent piece of theatre.

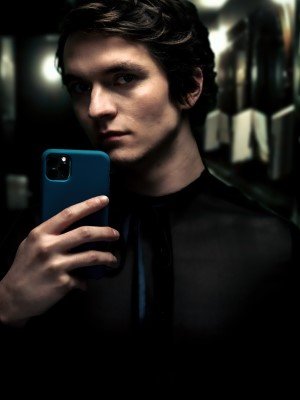

This Dorian (Fionn Whitehead) starts out as a sweetly naïve English lit undergrad trying to make it big on YouTube, aided by his rakish BFF Harry Wotton (Enoch), family friend Lady Narborough (Lumley), and besotted benefactor Basil Hallward (Tovey). Basil, a closeted programmer who’s made little effort to conceal his feelings for Dorian, plies him with gifts – clothes, mobile data, a smart phone – and offers him a very special filter that will ensure his pictures will remain ever flawless and ageless: “a perfect digital Dorian”. There’s no catch, because the price is something that carries little currency in the digital age: your soul.

Filters give the illusion of perfection. They are insidious because they are invisible, and they make you feel as if being beautiful and happy and successful is natural for everyone in the world but you. Uploading a selfie to the digital panopticon takes deliberation, intent, and often deceit: the background, the lighting, the clothes, the hair and makeup, the filter – even the most spontaneous looking snap is a meticulously oiled machine. As Basil says, we spend our lives comparing ourselves to everyone else’s highlights. The greatest trick the influencers ever pulled was convincing the world that they woke up like this.

In many ways, the amorphous, abstract identity of social media is embodied by Basil himself, who becomes both the painter and the canvas. Basil, who we rarely see ‘in the flesh’, is simultaneously omniscient and insidious. Tovey, one of the finest actors working today, is characteristically magnificent here – but I’m not sure how I feel about Basil, rather than Harry, being Dorian’s tempter. In the novel, Basil didn’t want Dorian’s soul, he wanted his heart. But, perhaps, in order to translate the essence of the story, it’s necessary to share some of Harry’s original menace with Basil, turning the sombre, soulful painter of Wilde’s original into a low-key Svengali.

The mechanism of the Faustian bargain is reversed here too – the painting in the novel preserved Dorian at his peak, and grew more decrepit as his sins accrued, but here the filter enhances Dorian’s onscreen beauty while his flesh rots in the real world. The visual effects marking Dorian’s physical decline are brilliant and subtle – I truly couldn’t tell whether it was makeup or CGI – and Whitehead’s transformation into a Sargon of Akkad or Onision-esque shock jock is genuinely unsettling (the moment where he starts glitching between his two faces was particularly eerie). What’s less convincing however is his success as a social media influencer.

‘What if Joe Sugg became Jake Paul?’ That’s seemingly the question posed by the play, and we’re told from the outset that wherever Dorian goes, he charms the world – but that’s simply not the impression we get from the sweet, sensitive, introvert presented here. And his rapid rise to fame never fully convinces, because while his clothes get progressively fancier, his manner, home studio set-up, and even the editing style never rings true (the fairy lights on his shelf were a nice touch, though). Emma McDonald’s Sibyl Vane is far more authentic: McDonald captures Sibyl’s kindness and her fragility, and she really nails the Insta aesthetic right down to the dreamy line delivery and the flower crowns.

Sibyl tragically falls prey to the toxic celebrity culture normalized by Harry (Enoch), rebranded here as a louche Made in Chelsea-esque socialite who lives the decadent lifestyle of a reality star. Enoch gives easily the most entertaining performance in the play, not to mention the most authentic interpretation of his literary counterpart, sprawled across a velvet chaise-lounge and elegantly sassing the ‘incessant’ barrage of theatre livestreams in #Lockdown1 like a latter-day Contrapoints.

His scenes with Whitehead and Tovey are mesmeric; Filloux-Bennett transforms the subtextual queer yearning underscoring the novel into text, and even separated by a screen, a Wi-Fi connection, and who knows how many miles, the chemistry between the central trio is off the charts. Wilde once confessed that he could ‘resist everything except temptation’. Social media is a creature of temptation, luring you in with a clickbait headline or an exclusive tell-all. It promises everything and gives nothing. It can facilitate cruelty without conscience or consequence and lives have been ruined, lost and taken. And none of us can say it’s not our fault: responsibility is fragmented between everyone who takes part in and enables this vicious culture of competition.

Lumley, sublime as always, delivers a monologue on how social media is ‘viral’ in every sense of the word: a poisonous contagion that’s infected the whole world. But just as The Picture of Dorian Gray showcases the internet’s ugliness, it also illustrates its beauty: its ability to connect people from across the globe in the shared experience of storytelling. Far from the isolating spiral of the doom scroll, this production illustrates the joy of collaboration, of creativity, and of art persevering in the darkest of times.

The Picture Of Dorian Gray | Theatr Clwyd is streaming online until Wed 31 March. Tickets are £12 each (one per household) including a digital programme and 48 hour access that allows for flexible viewing.