A monochrome Zoetrope of cross- continental imagery.

“Created in collaboration with Peruvian artists and long- time collaborator, composer Steve Blake, ‘Laberinto’ continues Anderson’s work around misconstruction of reimagined lost dances, leading the audience on a serpentine journey into the labyrinth, into worlds beyond death.”

The piece was performed at Bristol’s Old Vic in their Weston studio, an enchanted yet cosy space which fit the themes of Laberinto perfectly. This meant the dancers were really amongst the audience, almost close enough to touch but certainly close enough hear and maybe even feel their breath.

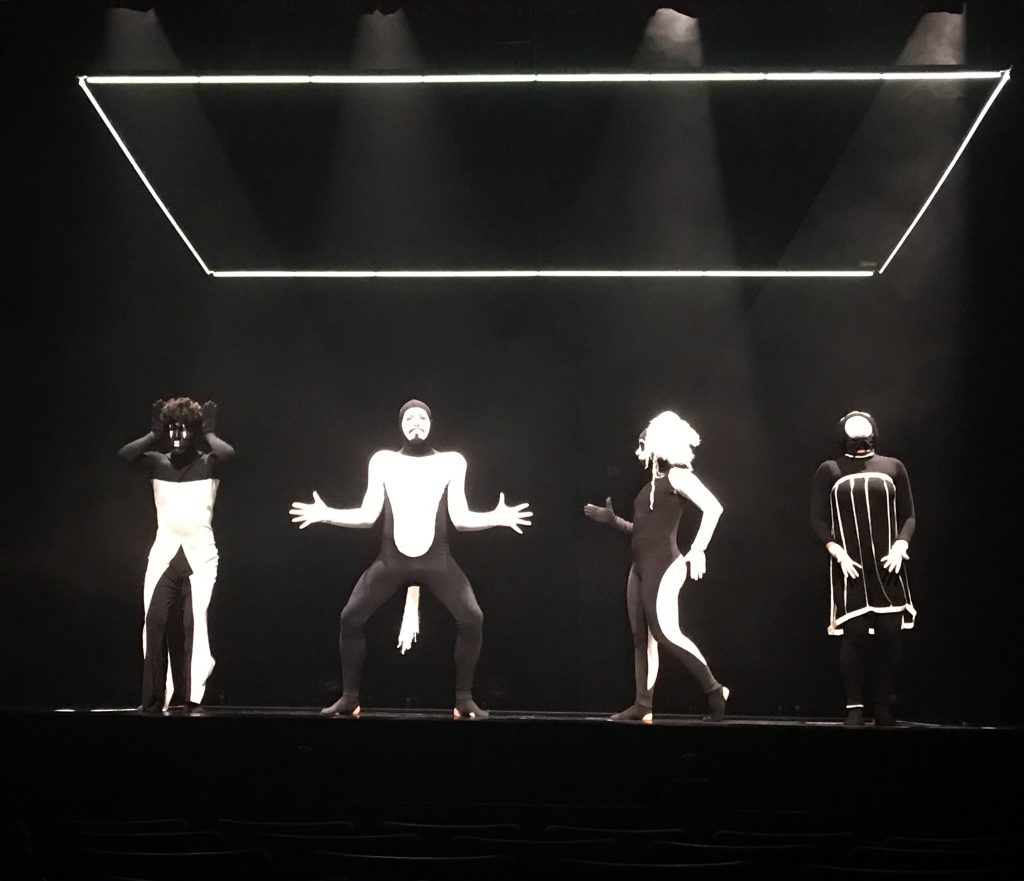

The dancers begin the piece with grounded movement which seems heavily influenced by Capoeira, an afro-Brazilian martial art form. They create strong shapes, providing visual imagery for the audience which is almost like a caricature or cartoon. This makes characters for each performer within the monochrome zoetrope of cross- continental imagery that emerges on stage.

The dancers hold their own persona within the piece, each with their own personality and therefore, their own characteristics. This allows the audience to form a relationship with each, creating space for light- hearted comedic moments which feature regularly within the piece and to the very end (including the bow). These add to the theatrics of the performance and provide breaks from the intensity of the images throughout. Also making the piece accessible for those, who are not necessarily from an arts background.

I adored the stark contrast between the characters, whether that was being devilishly camp or oppositely, stern and unphased. The posture of these really played true to the role. They often carried a Parisian ‘laissez-faire’ attitude which occasionally indulged us in their inner flamboyance. However, that isn’t forgetting the shift in physicality when performing sections that deemed more heavily tribal influenced. The dancers would then adopt a curved and more grounded approach, contrasting the seemingly European personas they were previously carrying. Sadly, as the performers tired, it did seem as though the sparkle of what were such strong, captivating personalities had become more distant and less embodied by the dancers.

The costumes, all variations of monochrome catsuits, hold reference to French icons such as Marcus Marceau as well as to Incan or Native American masks. This fusion of European and Latin American aesthetics is constant throughout the piece, both in imagery and movement. The use of face paint on the face enhances the characters in which the dancers play. With strict monochrome and neutral expressions, it is their physicality which tells us of their individual stories. Only to be broken with exaggerated facial expressions or the use of the tongue which strikes contrast to the sullen monochrome otherwise. Imagery like the sticking out of the tongue and piercing stares relate to that often seen in tribal rituals. This is heightened in the penultimate section of the trio. The trio is made up of a solo and a duet. The soloist seems to be trapped within a shamanic ritual between the other two dancers. The two dancers appear to be chanting around the soloist but not verbally, physically. The shamanic chanting is created via the use of hands and gestural movements, almost like a text. Repeated, over and over, each time with more power and vigour, growing in strength and intensity.

Throughout the piece the dancers’ hands will never be seen in a fist, but always splayed or stylistically positioned. Often the hands and arms will make references to whacking or vogueing foundations, often crossing over with that of 1980s catwalk models or magazine covers. This shape of movement is always precise, with transitional movements from one shape to the other. These shapes provide the context for the audience, often presenting imagery from familiar historic images. Not only supermodels but mimes, jesters, court dancers and circus performers. I did question at times which images have been used to make the choreography, as although some were obvious in their links, others not so much. There seemed to be expressions that linked with that of ‘Uncle Tom’ propaganda from the 1950s but whether that was purposeful or solely my connections, I am unsure.

The choreography itself relies on a mixture of devised games (such as freezeframes or adding to the picture) as well as the use of strict patterns playing with timings, canons, shape and poise. The accents of the choreography tended to swap between ‘hits’ and breaks’, meaning sharp held movements and sharper movements that then blend into something softer. The pathways of the piece were most intriguing and formed a key role within the piece. The characters would glide past each other, whilst in strict canons but along unusual pathways meaning as the audience, your eyes were constantly drawn to different areas within the stage.

The set simply details a square of flooring which is matched by a dangling box light above. This cube of parameter provides ample space for the performers to move and with their grounded movement quality, they seem encased within the space and we the audience are peeking through the looking glass. The strict spacing provided by the set allows the structure of the piece to provide breath and more importantly to reset from scene to scene. Almost as though when the dancers aren’t within the set, they are offstage (although they continue to pursue their characters and to respond to what is emerging on stage).

I was fortunate to witness the Q&A at the end of the performance which added further insight into the process of creation and how such a project came about. I was happy to learn that photographic images had been one of the core ways in which the piece had been created and that the piece focussed on these shapes and imagery throughout. It’s wonderful to see such open ways of creating and these types partnerships taking place. I look forward to seeing more from such an emerging professional company and wish them the best of luck on the rest of their tour.