Robinson, the latest creation of director Mathilde Lopez and John Norton, artistic director of the company Give It A Name, is taking shape in the Stiwdio, the large room part of Chapter Arts Centre. Robinson is as much a sound exploration as a textual engagement with Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe and Michel Tournier’s Friday. Defoe’s book, published 300 years ago, is a dreary propaganda for colonial exploitation, while in Friday, or The Other Island, written in 1967, Tournier explores the relationship between our ideas of civilisation and of noble savagery. In the hands of Mathilde Lopez, Robinson is a parable of solitude, which is conveyed through an innovative use of sound, designed by John Norton.

I sit down and I am given headphones. Every member of the audience will wear them. I hear the waves of the sea, the tweeting of birds, Caribbean music, and Bianca, played by Luciana Chapman, reading, but not in both ears. The headphones and mics are binaural, to recreate how our ears perceive sound. I hear Bianca speaking softly in my ear as if I were reading a book. I hear birds tweeting and a mosquito buzzing around my left ear evoking a tropical island.

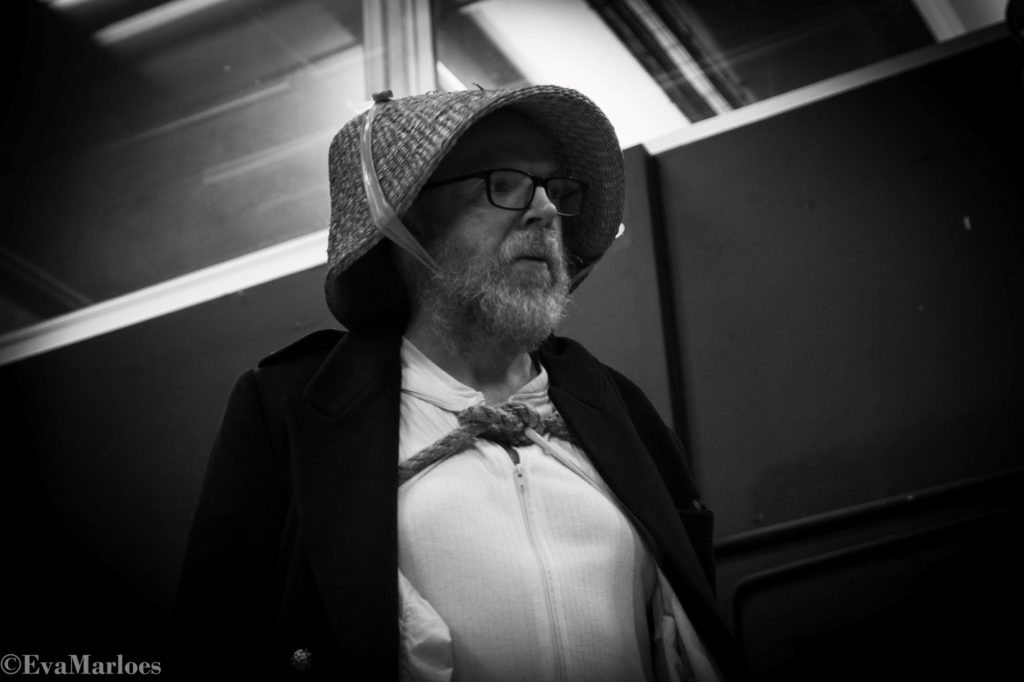

The stage, for the time being, consists of three tables stuck together lengthways cutting the space in two. This will later be replaced by pallets filled with various materials, including cans and empty plastic bottles. The actors perform on the tables and around them. They’re still finding their feet. The text is not finalised, the action still to be worked out, and the cues set. The play is in becoming. I’m witnessing the creative process, which, under Mathilde’s direction, is playful and cooperative. Mathilde often laughs. She laughs at what the actors come up with, she laughs at herself. She makes suggestions, gives indications; she never raises her voice, never criticises. It’s always ‘shall we do this,’ ‘can you do this,’ and ‘thank you.’

A big black box arrives. There’s dough inside. Mathilde has fun taking it out of the box and playing with it. Her happy and excited face is like that of a child. Luciana punches the dough while John, who plays Robinson and is an experienced bread-maker, kneads it. John wants to throw the dough to Luciana. She’s afraid of missing. She doesn’t. Mathilde encourages the game. She thinks that Luciana should drop the big blob of dough on the table. Luciana has put the big blob of dough on her face. Mathilde laughs and says, ‘It’s a bit Elephant Man.’ Turning to sound tech Jack, Mathilde asks for a recording of John as Robinson saying, ‘Can you put the soporific John?’ I stand next to them. It’s intimate and warm in a very cold room. I listen to Luciana reciting her piece. Mathilde, John, and I listen while playing with the dough. It’s like children playing quietly while their mother tells them a story.

This story is one of solitude, colonialism, capitalist ethic, and freedom. It begins with Mathilde’s love for Tournier’s work. In Friday, Robinson has sex with the island and even with the child of the island. Mathilde has focussed on solitude and the antidote to solitude: reading. ‘When you read, it has your voice.’ In Robinson, Bianca reads the book Robinson Crusoe directly into our ears, as if it were our voice. The solitude of reading a book is ‘not the solitude of watching telly,’ she tells me. In reading we use our voice, our rhythm, we are part of the book. ‘Your voice becoming a book is an enormous, physical exercise in compassion,’ says Mathilde. By saying the words in the book, we get closer to the characters and understand them. ‘It’s much harder for actors to remain oblivious to the suffering of the character they’re playing because they’re saying those words.’ Reading is thus a way to open ourselves to others, practise empathy, and participate in the humanity of others.

Robinson is alone on the island for 28 years. We participate in his solitude, but we’re also horrified by his misogyny, racism, and colonial attitude to nature. The novel Robinson Crusoe is a ‘twisted inheritance,’ tells me Mathilde. Facing up to the slavery and colonialism of the novel, makes you deal with where we’re from. In Mathilde’s play, the passages on slavery are not sanitised. They are kept and dealt with. Bianca gets angry and plays Gil Scott-Heron’s Whitey on the Moon, which in 1970 denounced American social inequality and racism and that is still relevant.

Today, in a world of extreme inequality, where the relentless pursuit of economic growth is threatening our planet’s very existence, Robinson’s obsessive work on the island mirrors our belief of constant activity as a value. ‘It’s morally right to do a lot,’ says Mathilde. The myth of self-reliance of Robinson is but a fig-leaf for exploitation of the land and of the labour of others. Robinson ‘has to do all the time because he’s terrified of living.’ In Tournier’s Friday, when Friday appears and makes all his goods explode, there is a shift in Robinson. He cannot go on in the same way. He no longer imposes ‘civilisation’ on the island.

Robinson’s ‘civilisation’ rests on slavery and the unsustainable use of nature. He looks at the world and the island as a good, as Mathilde explains, just as when we look at one another in terms of what we can get out. ‘Nothing has a value in itself. Everything is a means. The island is only a means for him throughout … Freedom starts at the point when things stop being simply means.’ Nature and human beings are value in themselves. At a time when we might feel discouraged at world governments’ inaction in tackling climate change and inequality, it might be tempting to despair. As Robinson reminds us, despair is a sin. Mathilde says, ‘bad fortune happens, but your own reaction to it is your responsibility.’