Rebus: Long Shadows is a new story written by critically-acclaimed author Ian Rankin and adapted exclusively for the stage by award-winning playwright Rona Munro. Starring Ron Donachie, Cathy Tyson and John Stahl, the story follows the titular DI, one of Scotland’s most famous fictional detectives, now retired, as he exhumes the faux pas of the past to find justice in the present.

Though I don’t claim to be a Rebus aficionado by any stretch of the imagination, I’ve enjoyed the various incarnations of the character, though for different reasons. DI John Rebus, played onscreen by John Hannah and Ken Stott, is the archetypal hard man, a gruff detective and former SAS soldier with PTSD and a serious drinking habit. Hannah’s Rebus was a youthful yet world-weary DI with a whole host of personal demons despite his fresh-faced looks. Stott’s Rebus, replacing Hannah in season 2, was a more convincing cynic given his age and natural gruffness. Both versions boast a bleak brutality, but Hannah’s inner monologue denoted a more internal, psychological approach, whereas Stott’s Rebus was more external and thus retained a greater sense of mystery and ambiguity.

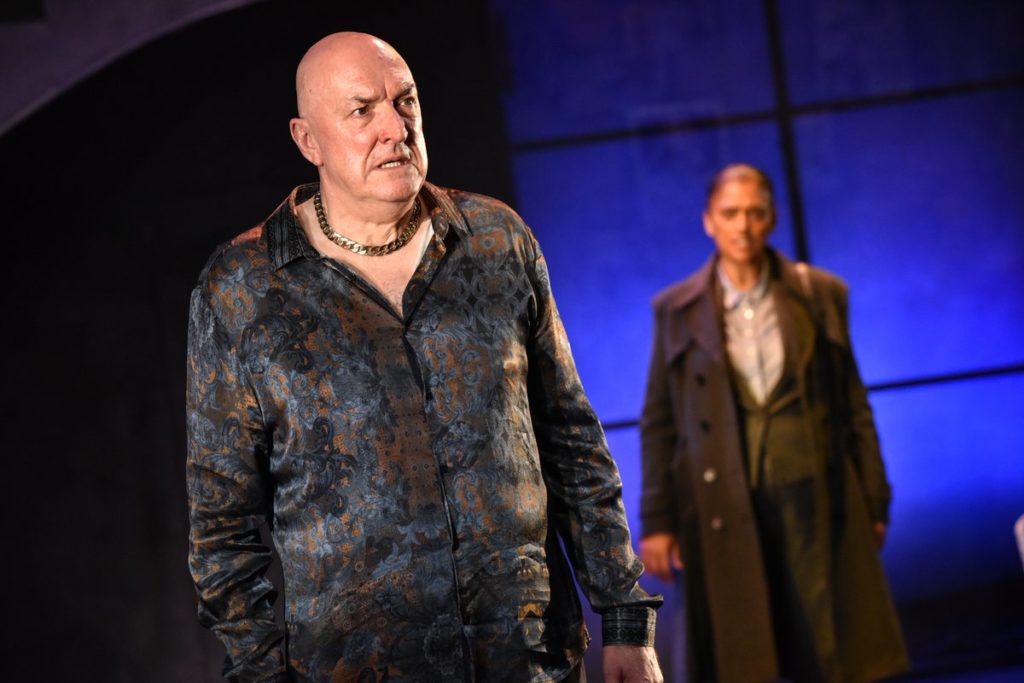

Long Shadows’ Rebus seems to be pitched somewhere between the two, played here by Ron Donachie who portrays the character in the BBC radio dramatizations of Rankin’s novels. Donachie is a very genial stage presence, a lovable curmudgeon who is plagued by the ghosts of past. Rebus is not so much an analogue detective in a digital age as a displaced Diogenes trying to make it in millennial Edinburgh.

It was disappointing not to see Cathy Tyson as Rebus’ procedure-driven protégé DS Siobhan Clarke (played by Gayanne Potter/Claire Price in the series), but understudy Dani Heron does a great job as the jaded DS even if she doesn’t look old enough to have been working a case for a quarter of a century. Her banter with Donachie is one of the show’s highlights, as both actors ably conjure that catty camaraderie of a long-lived friendship. She also gets one of the show’s best lines when Rebus frets about ‘the way lassies dress these days’, by responding that ‘young women can’t be prisoners of their fathers’ fears’.

The cast is brilliant across the board, from Eleanor House and Ellen Bannerman as the ghosts of the victims Rebus failed to save – the former of whom also plays the dual role of (murdered) mother Maggie and (surviving) daughter Heather – and Neil McKinven masters multiple roles with charm and skill whilst making each one distinctive and memorable. However, the standout of this production is John Stahl as ‘Big Ger’ Cafferty, Rebus’ amiable nemesis. There’s a layer of artifice to every actor in the show except Stahl, who imbues an earthy authenticity into the vibrant, larger-than-life (in name and nature) character. Stahl’s deliciously imperious performance captivates from the second he steps onstage, slipping seamlessly from debonair to devilish in a way that could have be cartoonish in the hands of a less capable actor. His performance is worth the price of admission alone.

Rona Munro’s script is interesting and engaging, and

Robin Lefevre’s skilful direction guides the audience through the murky mystery. The surname Rebus originates from the phrase ‘Non verbis, sed rebus’ (‘not by words, by things’), a phrase which describes a form of heraldic expression used in medieval times that used symbols, pictograms and illustrations to represent new words/phrases. This was taken up by Sigmund Freud, who believed dreams could be (re)interpreted in a similar way. It’s a fitting name for a gritty detective who has to sift through reams of fakeries and facades to find the villainy behind the civil veneer.

The production has a number of discretely creative touches, predominantly Ti Green’s evocative set featuring a central curving staircase that takes us down into the lair of Rebus’ mind, and a set which functions interchangeably as a poky flat, a nightclub, a pub, and a swish penthouse suite. The Gothic touches of the ghostly apparitions (aided by Chahine Yavroyan and Simon Bond’s lighting) are effective as they berate and motivate Rebus, but their near-constant presence reduces their potency. This element might have been more effective if Rebus had been the lead investigator of the cases in question, which would have given a sense of urgency and regret, and a more compelling motivation beyond just a general obligation to justice.

As such, the mystery of who the true antagonist is falls a little flat, because it’s fairly obvious from the moment they appear. Relocating the crime drama to the stage already reduces the nuance of a book or film/tv show, which can include breadcrumbs in the background – a throwaway glance, a name on a file, a news report – whereas onstage everything is rather unambiguously right there in front of you. The scene at Cafferty’s swish apartment, while engrossing, goes on for far too long, and despite the talented female-driven creative team, DS Clarke is frustratingly side-lined by the narrative, and Eleanor House’s Heather (though intriguingly layered) is stopped mid-potential by the arbitrary ending. I would certainly be interested to see how her character develops, especially in conjunction with Stahl’s Cafferty, if we ever get a sequel.

Interesting and enjoyable, Rebus: Long Shadows is a compelling addition to the longstanding, multi-media mythos of its eponymous investigator. Playing at the New Theatre until Saturday 9th February, it’s well worth a watch, especially if you’re already a fan of Rankin’s crotchety copper.

One thought on “Rebus: Long Shadows, New Theatre Cardiff by Barbara Hughes-Moore”

-

Pingback: REVIEW Looking Good Dead, New Theatre Cardiff by Barbara Hughes-Moore - Get The Chance

Get The Chance has a firm but friendly comments policy.