This is not a new version of the Chekhov classic, but a ‘re-imagining’ by Welsh writer Gary Owen, of Killology & Iphigenia In Splott fame. Owen relocates it from 1890’s Russia to the Pembroke coast in 1982, just prior to the Falklands War, which makes for a very interesting choice.

It feels like every dysfunctional family drama you’ve ever seen, until you realise Chekhov originated the idea of real characters, with real problems, talking like real people.

Family matriarch Rainey, who has crawled into a bottle after the death of her son over a decade ago, followed soon after by the suicide of her husband, is virtually dragged back to the family home from London by Anya, her youngest daughter. Her self-destructive lifestyle has lead to the family home on the Pembroke coast being auctioned off to pay the debts.

Val, her eldest daughter, has held things together, but they need Raynie’s permission (and signature) to save it. All agree that the only viable option is to sell off the ancestral cherry orchard for redevelopment, but will she see it that way?

This play is incredibly funny and well-worth seeing, if only for the way Owen makes it so accessible to Welsh eyes. The ‘Russian peasants’ now come from housing estates, the decaying aristocracy are English interlopers, and the Communist revolutionaries are now Thatcherites, sweeping the past away without a thought or concern.

At the heart of the play is the idea that the future is farther away than we hope, while the past is always closer than we’d like. The characters here are continually haunted, not by spirits, but by the ghosts of memories, taunting them with remembrance.

Rainey tries to forget through excess, her guilt at losing her son gnawing away at her, like a rat sown inside her skin. In the end it causes her to take drastic action, and Denise Black brings all this out in a masterful performance that makes you feel sorry for her, even while she’s being a monster to all and sundry.

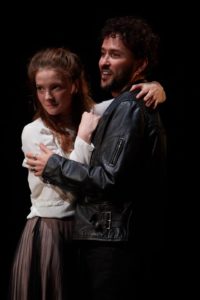

The entire cast take their moments when offered, yet still make this a true ensemble piece. Morfydd Clark is sweetly sensual as the young Anya, while Hedydd Dylan as her elder sister Val, shows us a woman who tries to run other people’s lives, but fails at her own.

Simon Armstrong as Gabe, Rainey’s brother, is amusingly ineffectual, yet quietly sharp. When Val talks about Rainey not telling him about her plans to leave he replies “We’ve been brother & sister half a century. Through awful things. Do you think saying ‘goodbye’ makes any difference?”

Alexandria Riley gives us a Dottie that is down to earth yet shows the love/hate relationship she has with the family, while Richard Mylan is funny, while also imparting a wise naïveté to Ceri.

Mathew Bulgo, given the task of Lewis, the ‘poor boy made good’, effects a performance of subtlety that defies the historical villain the role has been seen as. With the insults he endures from the others, and denied the role of ‘family saviour’ by Rainey, it’s hard not to feel sympathy for him.

Writer Gary Owen conveys a situation full of layers, and also offers some nice ironies. Ceri’s expectations of Margaret Thatcher getting the blame for the Falklands War being one, Gabe’s job offer as an investment banker another.

When you add all this to Rachel O’Riordan’s deft direction, Kenny Miller’s intriguingly skewed set, and Kevin Tracey’s ingenious lighting, the Sherman Theatre demonstrates yet again that it is punching well above its weight in the theatre world.

There is so much going on here that I actually re-read the script in one go afterwards, and was still as gripped as I was by seeing it. The play is funny, ironic, witty, sarcastic and quietly heartbreaking. It is a story of loss, of people, places and things, and how memories both haunt and define us.

As F. Scott Fitzgerald once observed: ‘We beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past‘.

http://www.shermantheatre.co.uk/performance/theatre/the-cherry-orchard/

Kevin Johnson

Get The Chance has a firm but friendly comments policy.