Hi Tess great to meet you, can you give our readers some background information on yourself please?

Thank you so much! I’m a playwright and novelist living in Cardiff. I was born in the Midlands but grew up in Oswestry along the Welsh border. I spent my teenage years at school in Denbigh, before going to London for university and work for some years. Some of my writing has been produced in London theatres, as well as at the Edinburgh Festival, and also in the States as part of human rights campaigns. I’m also a refugee rights activist, volunteering with two charities, Calais Action and a choir of refugees and friends, Citizens Of The World Choir.

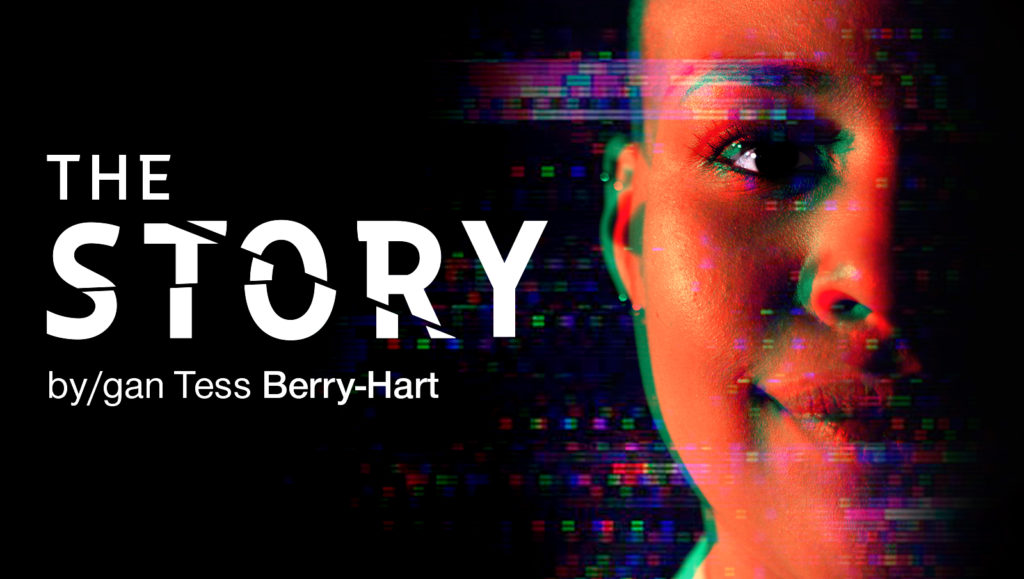

My latest play, “Cargo,” about a group of refugees travelling in a cargo container was produced at the Arcola Theatre London in 2016 and later toured by the Turkish State Theatre last year, and I’ve also previously written a couple of young adult novels about climate change called the Genopolis series. My new show “The Story” was commissioned by The Other Room Cardiff, as part of their Violence series, and will be on from 8 – 25 October 2019.

So, what got you interested in the arts?

My dad was a painter and my aunt was an actress, my brothers are musicians so it’s definitely in the family blood. I read a lot from an early age so I always wanted to write, but also I think I probably moved into writing because it was a toss-up between that and music, but with two brothers as musicians there was more space to find my way in books and theatre for me. Family dynamics (I’m the baby of my siblings) are responsible for an awful lot!

Why do you write?

Therapy! I suffer a lot from depression and anxiety, and unfortunately I’m not one of those people who can do yoga or meditation for calming myself because my brain turns into a screaming bear pit. Instead I manage intrusive or cataclysmic thoughts by creating and writing, whether influenced by or as a direct block to worrisome stuff so I can immerse myself somewhere else for a few hours, or process things that are happening to me. I don’t find that depression and anxiety stop me writing, quite the opposite in fact; my last two pieces were written in the pit of depression earlier this year when I could barely get out of bed, and writing was pretty much the only thing that got me through. It’s a bit like playing beautiful music to block out the neighbours fighting, if you turn it up loud enough, then you can escape for a while.

There are a range of organisations supporting Welsh and Wales based writers, I wonder if you feel the current support network and career opportunities feel ‘healthy’ to you? Is it possible to sustain a career as a writer in Wales and if not what would help?

To be honest, it’s always going to be really hard to be a “full time writer”, wherever you are in the UK, because there’s only so much resources to go around, so both in London and in Wales I’ve had to juggle various things to keep going. I’ve noticed in Wales that the Sherman and Clwyd have been supporting many writers and well as the various writers rooms at the BBC. If I could identify anything it would be that it would be targeting the missing areas of representation in supporting writers, do we need to support more female writers, more writers of colour, etc. The Violet Burns Award by The Other Room Theatre is a very good example of supporting female artists, and I think that it would be good to see more of initiatives like this.

If you were able to fund an area of the arts in Wales what would this be and why?

I’m very interested in mental health and neurodivergence so theatre and groups by and for people affected by various learning or communication conditions, such as Hijinx, or shows like Splish Splash by NTW last year are really valuable. I’m increasingly interested in types of communication that don’t depend on language, because theatre is all about communication, so to try to find ways of telling stories that don’t hinge on words themselves is something that I’m thinking about now.

Can you tell us about your writing process? Where do your ideas come from?

Ideas get triggered by a range of things; my experience volunteering for instance, or a news story, or domestic events in my family perhaps. There’s always a period of downtime once a script is finished or a deadline met, where I’m the most uncreative person ever because it feels like I’m all used up; but having a few new hot ideas always in my back locker to plan or feel excited about helps my mind feel active.

Can you describe your writing day? Do you have a process or a minimum word count?

I think of writing as a daily practice, like yoga or meditation or tai-chi perhaps, because it has therapeutic value for me personally. The process does change according to whether or not the work is commissioned or whether it’s an idea that I’m working on as a spec script, or a deadline is approaching, but essentially I try to do a bit every day, whether it’s simply allowing myself time to let ideas germinate, or taking half an hour to try to get some raw material down, or editing over something that’s been written. I think most writers have different periods when they find it easier to either edit or create or ruminate, we’re not word machines. Luckily I’m quite a quick writer if I know a deadline is coming, so deadlines really help me to pace myself. I’m definitely not one of those writers who sits down and knocks out a thousand words every morning, but keeping it in the active part of my mind where I’m either writing something or thinking of writing something helps me.

You are a verbatim storyteller, how do you resolve the challenge of telling a gripping tale and sharing the truth of the diverse voices you work with?

Interestingly, I don’t see myself as a verbatim storyteller. The majority of my work is not verbatim (The Story for instance is fiction), so collecting verbal stories and contributions from people in order to shape it into an artistic work – is something that I’d only use if it was a real-life non-fiction story I was telling.

However, being a writer can be quite lonely so verbatim offers a nice collaborative environment of talking to people and getting out of your own head for a while and into someone else’s. You get to meet hundreds of different people from different backgrounds that you might not otherwise have known in life, and open yourself up to all sorts of interesting possibilities. Right now for instance, I’m working as a librettist with four different choirs to listen to the members’ stories and help transform them into an opera by collaborating with a composer as part of the “Singing Our Lives” project.

And yes, sometimes it’s hard to balance the objective truth of what you’re told with the endless writer’s itch to edit and augment reality, but I switch on different parts of my brain to shape what’s best about the material that I’m given into the themes and actions of the contributors themselves. I find that quite easy to do, as it takes the pressure off to “create” – and in most of my verbatim projects, the story is there waiting to be found anyway.

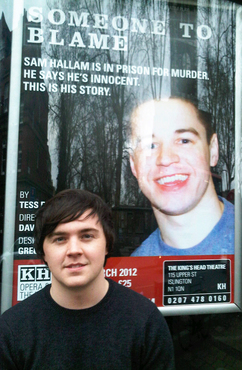

You were commissioned by the King’s Head Theatre to write the verbatim theatre piece Someone To Blame (2012), to highlight the real-life case of Sam Hallam, a 17-year old convicted of a murder he did not commit. Could you describe how you approached this commission and the subsequent developments in Sam’s story.

This was perhaps the most unusual commission I’ve received, which was part of the campaign to highlight the inconsistent evidence that convicted Sam of murder although he wasn’t even there. It was the first non-fiction play I had done, and given the legal issues I decided to work in a verbatim style, reading my way through huge stacks of court testimony, police interview reports and witness statements to use people’s own words about the events to create a piece of theatre. We also visited, interviewed and transcribed the words of people who were there at the time, including Sam in prison a couple of times.

I have a law degree which helped me get through and absorb the mass of evidence, and put together a script which started off with a gang fight in north London during which a young person was tragically stabbed to death. It then followed the various characters implicated in the murder, and critically examined the testimony which had convicted Sam.

The play was produced by the King’s Head a few weeks before Sam’s appeal. When Sam’s case was finally heard, the cast and crew of the play were all in the gallery at the Court of Appeal in London listening to the lawyers outlining the evidence. One of the actors leaned over and whispered to me, “It’s just like your play, isn’t it!”

What we hadn’t expected was that the judges, having heard only three hours of evidence, decided to free Sam there and then as his conviction had been so demonstrably not proven. Sam walked free from the doors of the courthouse that day and got sprayed with champagne by his friends, and there was a huge party in Hoxton for him afterwards. Sadly Sam was denied compensation for his unlawful conviction as the government had abolished automatic compensation for victims of miscarriages of justice.

What excites you about the arts in Wales?

I spent a long time in the London arts scene after I graduated from university, and what I really love about the Welsh arts scene is that it’s smaller yet has a vastly more supportive feel from the theatrical community, as well as from the audiences and community towards practitioners. Artistically there seems to be a lot more dedication to process in rehearsals and development support.

What was the last really great thing that you experienced that you would like to share with our readers?

I was shortlisted for the inaugural BBC Wales Writer in Residence award this year which really excited me and made me feel honoured to be included. It was especially meaningful because I had written the script whilst getting through a very difficult emotional time in my life, and was a deadline that I really struggled with. I’m very glad I managed however, and I’m really grateful for the opportunity.

And finally, your new play, The Story, commissioned by The Other Room Theatre as part of their Violence Series, explores the language of violence and the stories we tell ourselves to justify violence against others. In an extremely polarised society what can this new play offer to inform, educate and entertain?

Since I volunteered in Northern France from 2015 and also in Athens and Lesvos in 2016, the rising populist right-wing rhetoric has really exposed how language has been weaponised and how words matter, whether it be the murder of Jo Cox or the rise in racist attacks and nationalist sentiments in the UK post-Brexit. The Story is also an examination of how the idea of humanity and what it means to be human is being increasingly deconstructed. Volunteers have been criminalised for pulling people out of the sea or giving out food because the recipients aren’t seen as “legal”.

On an artistic note, it’s also probably the most “theatrical” play I’ve written, and really demands a lot of the actors and team! I’m very grateful to The Other Room for giving me the opportunity to create something around these themes, and watching The Story come alive in rehearsals has been epic. People watching it are definitely not going to know what will happen next!

“The Story” plays at The Other Room, Cardiff, as part of their Violence series from 8 – 25 October 2019.

Fascinating insight. Clearly, a woman with great energy and heart.