The first image we see in Andrej Wajda’s Ashes and Diamonds is that of a cross on top of a small chapel. The camera pans down to find three men laying on the grass next to the chapel, one of them is sleeping. An innocent little girl appears and asks one of the men to open the chapel door for her. A nice summery image for a pleasant summer’s day somewhere in Poland. Then in the distance a car approaches, the men rush to their feet, each brandishing machine guns and tell the little girl to get lost. Bullets fly, the car comes crashing to a halt, the driver falls out, machine gunned to death. The passenger makes a run for it, bangs on the locked door of the chapel, but he has nowhere to go. The three men machine gun him to his death, as he falls he bursts into flames at the door of the chapel. One of the three men then panics, ‘let’s get out of here,’ he wails, and we realise that we’re not watching super cool hitmen but real human beings caught up in civil unrest in Wajda’s most humanistic of films. Later, after the three men have fled we realise that they’ve killed the wrong people as their intended target arrives on the scene. A worker surveying the dead bodies then asks, ‘can you tell us how long people will have to die like this?’ Ashes and Diamonds is a film that asks the toughest of questions.

Presented as part of Martin Scorsese’s “Masters of Polish Cinema” series, the film features in Scorsese’s list for his choice for the ten greatest films ever made in the 2012 Sight & Sound poll. The film is a key component of Polish new wave cinema, one of the most stylish of national cinema movements and just like the French new wave which came hot on its heels, Wajda and his fellow filmmakers managed to expand on the cinematic foundations laid forth by the Italian neo realists in the mid 1940’s.

Ashes and Diamonds is essentially the third part in Wajda’s unofficial war trilogy, although enjoyment of the film is not dependent on viewing the previous two. In the previous two films, A Generation (1955) and Kanal (1957), which both concern themselves with the Polish uprising during the Second World War, there is, despite the bloodshed amongst the upheaval of human morality, a great deal of hope and idealism. But come Ashes and Diamonds, this hope has evaporated and instead been replaced with despair. Even in spite of the fact that the Nazis have surrendered which people hear about over a loudspeaker yet barely react to, there is no Times Square esque V-J Day celebrations here, because for the first time since the war started, people can now envisage their futures and they don’t like what they see. Fighting the Nazis united them in hope, but now the war is over and the only people left to fight is themselves.

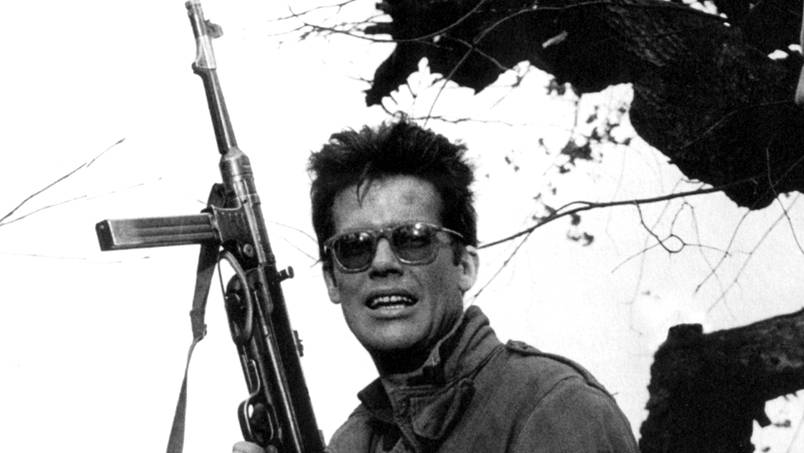

Set over twenty four hours in 1945, the overriding narrative of the film deals with the civil conflict between the pro-Russian People’s Army and the UK backed Home Army. The film is both a war tale and a tragic love story whilst also having the feel of an American hang out movie. The star of the film, Zbigniew Cybulski, incidentally one of the three shooters we meet in the opening scene, was often known, thanks largely to this performance, as the Polish James Dean. He certainly has Dean’s coolness and playfulness, whilst his impulsiveness throughout the film conjures up the image of Dean jumping from roof tops in Elia Kazan’s East of Eden (1955). Cybulski’s performance, his actions, his facial expressions, manage to capture the melancholic nostalgia of the story and of post war Poland, he says things like, ‘nothing in this country is serious anymore.’ He meets a girl, the wonderful and beautiful Ewa Kryzewska, who works at a hotel bar who says things like, ‘I don’t want any goodbyes or memories to remember when it’s over.’ This is a film where every line of dialogue has meaning and significance.

On the surface at least, Cybulski is the star of the film, but the true star of Andrej Wajda’s Ashes and Diamonds is Andrej Wajda himself. The whole film is a one hundred minute masterclass in cinematic framing. In one scene, Wajda frames Cybulski’s collaborator in arms Andrej, played by Adam Pawlikowski, in a close-up as he talks on the phone inside a telephone booth, over his shoulder is Cybulski leaning on a bar, then behind Cybulski in walks Communist Commissioner Szczulka, played by Waclaw Zastrzezynski, the man who Cybulski and co were originally sent to kill. In one shot through expert framing Wajda manages to convey the entirety of the film’s emotions and conflicts with stark simplicity. Throughout the film Cybulski keeps coming face to face with his past, in one scene he sees the crying fiancé of one of the men he killed in the opening sequence. Cybulski stares at her and Wajda holds and holds Cybulski’s gaze in a close-up. There are no words spoken yet by dwelling on Cybulski’s face Wajda manages to convey all the actor’s emotions, it’s almost as if we can hear his thoughts. This is pure cinema.

The images in Ashes and Diamonds are so profoundly striking it is a film that could be watched and understood with the sound turned off. The film ends with an unforgettable sequence that you will carry around with you long after the final credits have rolled. It’s visual poetry from start to finish.

Ashes and Diamonds (12)

Poland/1958/104mins/subtitles/12. Dir: Andrzej Wajda. With: Zbigniew Cybulski.

At Chapter Arts Centre from June 7th – 9th.

– See more at: http://www.chapter.org/ashes-and-diamonds-12#sthash.2nExviZK.dpuf