(4 / 5)

(4 / 5)

If you are not familiar with the style of Bouffon theatre, then you are severely missing out.

Myself having trained in this art and a huge fan of Red Bastard, was so pleased to see and be invited to a show using this type of theatre, so little seen or experienced in modern theatre, while being the right genre to grace our stages.

A brief outline of Bouffon; grotesque creatures are made with costume and physicality, to comment on taboos of the world. These clowns address these topics without barriers and put them almost uncomfortably into your face, leaving you not knowing whether to laugh, cry or be thought provoked.

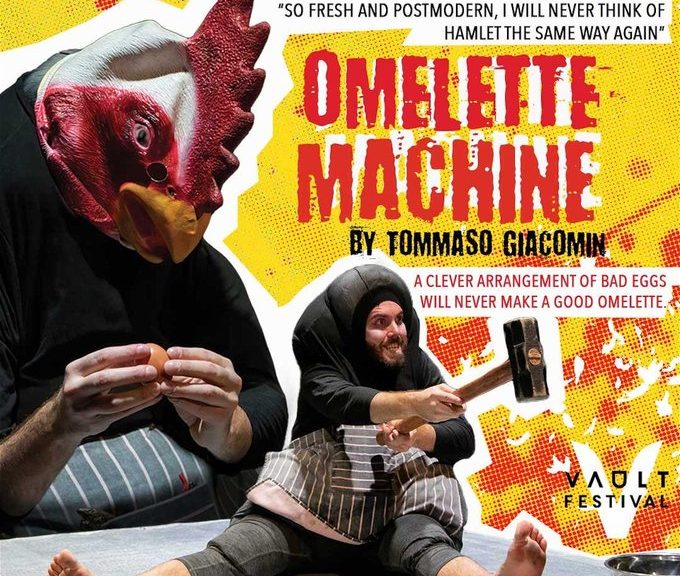

OMELETTEMACHINE, loosely based on Shakespeare’s Hamlet, addressing issues around family trauma, of power and mental violence and to some degree, of capitalism. A clowned chicken meets egg is forcibly made to work in his father’s butchery, unable to leave and tortured to massacre fellow chickens. He is unable to leave, and if so, commits punishments of almost cannibalism with “rotten” egg eating, smashing of eggs and chopping of chicken meat.

This production is very powerful; Bouffon aims to make the audience uncomfortable and Giacomin does this in spades. He isn’t afraid of addressing the audience, bringing them into the folds of his torture. This is through direct interaction, through the use of raw meat and blood-like liquid, through the beginning projection of live chicks in a factory. Real blades are used, unceremoniously chopping at raw meat; raw chickens still in tact and grotesquely danced on stage or come through the audience on a electric toy car. It’s these elements of surprise that are comedic but make you uneasy. It entirely and fantastically achieves what it is meant to, really making you think. And if you’re vegetarian like myself, there’s a barrier of disgust but admiration for the boundaries that are being pushed to make comments on these topics. A sense of “working for the man” comes to mind when Giacomin uses repetition to advertise his father’s butchers, with monotonous and repeated tasks and conversations. There’s the family trauma but also a sense of working for something and someone you are against.

Giacomin has the style of Bouffon on instant look; plumped up with padding and contorted physicality, he is comedic and difficult to look at, moving his face into an almost unrecognisable clown. When we reach the end of the production, he lays himself bare, releasing the shackles of his costume and returning to his natural features and this is when you truly realise the lengths he has taken in his bodily and facial contortion to create the character. If we had not seen him undress on stage before us, you would almost think they were two different actors. He is childlike, to meet the idea of his father’s control yet somehow uncomfortably adult, with the mixture of the two creating a feeling uneasiness. He is full of emotions of anger, of fear, of borderline mental illness and it makes it subtly chaotic, your body itchy with uncomfortability but entirely thought provoked. This is a triumph of Bouffon.

OMELETTEMACHINE is brilliant – it is everything that Bouffon is meant to be and leaves you laughing, uncomfortable and yet with a profound thought on family relationships and the capitalist world.