⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Dominic Dromgoole’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream is just that: dreamy. It has everything you could want from a woodland romp – gorgeous costumes, plenty of gags and superb acting, but is never cliché, nor rests on the Globe’s laurels.

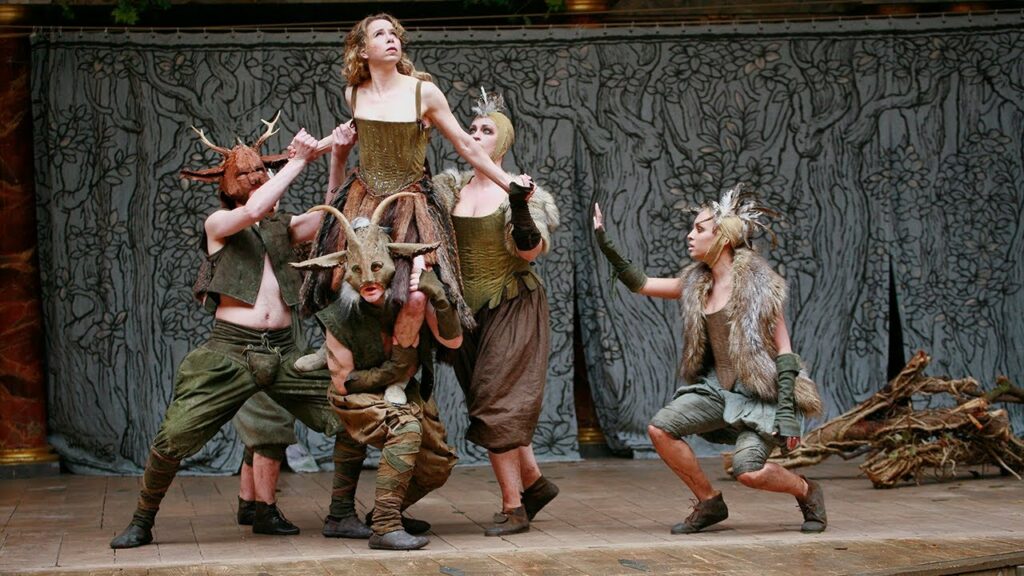

| The Fairy Queen (Michelle Terry) and her followers. Image: Alastair Muir |

This production uses both Elizabethan staging and costumes though you’d be mistaken to think it fusty: John Light’s Oberon and Matthew Tennyson’s Puck both bare their chests, while Michelle Terry as Titania skips about in a fur pelt skirt that looks straight off a runway. The fairies’ costumes are also stripped down; trousers and corsets are embellished with natural materials like twigs and mud, as well as animal features such as feathers and stag horns. Delicate winged creatures these fairies are not. Instead, they snarl and shriek like a wild chorus, adding an element of danger to the forest scenes. Their bestial and androgynous clothing contrasts heavily with the pristine, stiffly laced, and heavily gendered garments of the humans in the Athenian court. But when the four young Athenian lovers get lost in the woods, they gradually become more uncivilised and less dressed, which makes for an interesting crash course on the various layers of Renaissance garb.

| The lovers a little worse for wear – well, ‘the course of true love never did run smooth’. Image: John Haynes |

The set design by Jonathan Fenson is pleasingly simple: the existing polished brown wood and red ‘marble’ arches of the Globe suit the pomp of the court scenes, and these earthy tones, when coupled with foliage and green tapestry curtains, equally complement the autumnal imagining of the forest scenes. As an outdoor venue, staging Midsummer at the Globe is always a special experience, but the rejection of the usual floral, sunny features is a welcome change and actually matches the overcast day of recording rather well. Opting for a darker, cruder design captures the more mysterious and animalistic themes of magic and lust within the play.

The opening of the production begins uniquely with a dance sequence reflecting a battle between male swordsmen and female archers, in which Hippolyta is bested and won as a war trophy wife. This completely alters the meaning of the first lines between King Theseus and his new bride. They are not a lovesick couple longing for their wedding day but a growling Lord and his bitter captive (both roles played brilliantly with seething venom by Light and Terry). This patriarchal tyranny informs the next shocking scene where Hermia’s father reminds his daughter that the penalty for disobeying him is death. In the forest, we learn there is also trouble in paradise where the tension is mirrored between the fairy king and queen; themes of misogyny are not brushed under the woodland carpet and the threat of violence lingers here too. When the young lovers enter the realm however, things do take a turn for the ‘fancy free’. In this version, the line ‘What fools these mortals be’ rings true as the lovers are played less seriously – a valid interpretation for me, as Shakespeare’s device of having them ultimately wake up and fall in love with the ‘correct’ person is a silly notion in the first place. All young actors give accomplished performances, Hermia (Oliva Ross) and Helena (Sarah Macrae) as headstrong women and Lysander (Luke Thompson) and Demetrius (Joshua Silver) as hapless posh boys.

| All is not well in Fairyland: Oberon (John Light) threatens Titania (Michelle Terry). Image: Alastair Muir |

Stand out performances also come from Michelle Terry, the Globe’s current artistic director, whose Titania is just as haughty as her Hippolyta, though more full of the joys of spring – or summer. John Light adopts a husky Irish accent for his Oberon and his ultra-masculine portrayal contrasts with Matthew Tennyson’s boyish Puck. The pair makes a great duo, employing Sian Williams’ tactile choreography – the use of gymnastics and swinging ropes also bring out the production’s playfulness. The tactility flows into romance: everyone, regardless of gender or species, seems to be getting it on in this production.

| Oberon (John Light) is enamoured with his protégé Puck (Matthew Tennyson). Image: Alastair |

It’s Bottom, however, who steals the show; Pearce Quigley is a comic genius, his Salford accent thicker than gravy with cheesy chips and his performance raises belly laughs from the audience. The comedy is ramped up with the Mechanicals, a usual audience favourite, who certainly don’t disappoint here. The infamous roll call is blocked clearly and each actor’s intonation allows us to fully understand the dialogue. Though the Mechanicals’ questionable acting skills mean they shouldn’t give up their day jobs, director Dromgoole adds yet another trade to the craftmen’s collective wheelhouse – clog dancing. Bottom the Weaver and Peter Quince (a brilliant Fergal McElherron) clash fantastically; Bottom undermines micro-managing Peter (‘Peter?’) through constantly interrupting and forgetting Peter’s name, but the rivalry is ultimately settled with a ‘clog off’, where Peter whips out a delightfully anachronistic moon walk.

| ‘Take pains. Be perfect.’ The rude Mechanicals celebrate their play’s commission. Image: Alastair Muir |

The play within a play brings the comedy to a crescendo and is a great reward for the near 3 hour runtime, though this production is definitely no chore to watch. ‘Director’-cum-‘narrator’ Peter is in his element and his campy, over-bearing manner wouldn’t be out of place in any am-dram rehearsal room. Under his direction, the misguided players bring out a pop-up replica of the Globe itself, which is wonky and requires periodic mending by Snug (an understated Edward Peel), regardless of whether the sound of hammering and the piggybacking of actors is a tad distracting to both ‘players’ and their courtly audience. Things only get worse (or rather, better) when Wall’s (Tom Lawrence) huge costume threatens to eclipse the entire structure and his ‘crannied hole’ is set in a very unfortunate place. ‘Beauteous’ Thisbe (Christopher Logan) provides no respite to this theatre of the absurd as her portrait is visually terrifying, all garish face paint and huge hooped skirt which upturns in her death scene, though this is too drawn out and the audience’s laughter drops off a little. Despite the otherwise successfully overblown actions and slapstick tone, these elements are contrasted with many pregnant pauses, subtle glances and small gestures, all timed perfectly to alter the pace and heighten the comedy. As the play in miniature and play proper draw to a close, the cast have us eating out of the palm of their hands.

| The tragic tale of Pyramus and ‘Thingy’ (Christoper Logan and Pearce Quigley). Image: Alastair Muir |

The live music, composed by Claire Van Kampen, is sparse but used to good effect: the traditional fanfare frames the opening sequence, and periodic drums and strings create an eerie atmosphere to signify the faeries’ arrivals. The accompanying wordless singing is unearthly and a perfect fit; as such, it also closes the show with a final masque, categorising this production as both beautiful and haunting.

With innovative interpretation, visual flair and real comic wit, the Globe’s 2013 performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream is, dare I say, the best version I’ve ever seen. Acapella vocals and traditional yet naturalistic costume take Shakespeare’s deceptively dark comedy back to its roots, but in doing so, breathe fresh life into it. It’s passionate, stirring, and above all, funny – they must have taken Bottom’s plea to heart and took pains – for it was perfect.

| The ensemble in the closing masque. Image: Alastair Muir |

A Midsummer Night’s Dream is available to watch here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_cAwaNRIEF8