In our latest interview, Get the Chance community critic Barbara Hughes-Moore chats to director Alison Hargreaves, whose latest short film Camelot features in the anthology The Uncertain Kingdom. Produced by John Jencks, Georgia Goggin and Isabel Freer, the anthology assembles twenty visionary filmmakers to paint a portrait of post-Brexit Britain. Alison discusses her career, the urgent need to invest in the arts, and why it’s so important to give children the opportunity and the control to tell their own stories. Camelot was creatively led by a group of pupils at Idris Davies School in the Rhymney Valley in collaboration with professional theatre practitioners from May-July 2019, and is described as ‘Wales’ ancient legend reimagined by its future men’ .

This interview has been for edited for ease of reading.

Hi Alison, thank you for making the time to speak to me this morning. Can you give our readers some background information on yourself please?

I’ve been moving into film in the last 5 years, but my background is mainly in theatre. I’ve worked for organisations like Bristol Old Vic and Clean Break Theatre Company and other companies that have tried to find ways to reach people who didn’t necessarily have access to quality creative engagement and finding ways to democratise resources so that more people can have their voices heard and be represented. I’ve worked in criminal justice settings, in prisons, in different communities, different vulnerable groups, and in schools.

As a theatre fan, it becomes more interesting if going to the theatre teaches us something about our society that we didn’t know, and that means not telling the same stories again and again. Theatre and film should help you understand the society you live in and what you have in common with other people. That’s always been where my creative interest has been because the most impactful and exciting work has been made that way.

How important is it to support the arts?

We live in a country that doesn’t necessarily support the arts properly, and especially in education, so when I started to make films I was interested in documentaries that would give a platform for people who might have been under-/mis-represented. With a film, you can frame something in a new way, you can help people to feel a kind of complicity, and feel a connection to or empathy for people who they might otherwise have never really felt connected to. A film can take you inside someone’s inner life; it can help you understand the way someone thinks, whereas in the course of everyday life we sometimes live in bubbles and don’t always reach out to each other.

I think that the process of theatre-making is that it’s beneficial not only for training children for the creative industries (although it can often spark that interest); theatre-making is about working together, respecting ideas, having your own ideas respected, having a safe space to experiment and imagine new things, to support each other, to be supported, to tell a story, to connect with people and to learn and develop skills like devising and reinventing a story and making it your own. The devising process in particular is brilliant for children because its enables them to understand that they can rewrite a story, meaning they can have an influence not only in the way that a story is told but in the way that their story is told. This means they take some ownership, and have some control, over the story, which I think is huge for children who may not have the opportunities and role models; some people feel they are on a conveyor belt and the only thing they think they’ll end up doing are the things people around them are doing.

Engaging them in constructive creative process gives them an opportunity to really understand that the world is their oyster. What I was really interested in doing for Camelot is using theatre to engage the imaginations of those children so that a film audience could step inside their imaginations and see what was inside their heads, and for those children to be taking ownership of ancient stories, the sorts of stories that underpin our culture. These stories are handed down to us and they repeat ideas about who we are as a country, as people, and I think it’s really important that we don’t treat those stories as set in stone; that they come with their own biases and it’s important that everyone has their own interpretation and has an opportunity to decide for themselves what the story could mean and how its relevant to them. I was really interested to see what the children came up with – they’re at an age where they’re not self-conscious, where they are complete free-thinkers, but not given a huge amount of opportunity to do constructive creative work that doesn’t get graded. We tried to find a way to make sure every set of abilities could find a contribution to make.

This idea of reclaiming the narrative came across so strongly in the film – do you think it applies to the community as well, because the interconnectedness of people and the place they inhabit seems to be at the core of the film. The Pit Pond seems to be the axis of that. Is that an image that realty stood out to you?

Totally – I’m so pleased you got that! What’s interesting about the Camelot story is that it’s about building a kingdom of your own, creating a space for yourself. A lot of the rhetoric in Wales’ Leave Campaign was about a mythical idea of reclaiming your land – and those kinds of themes must be interrogated. It was time to reinvent the story rather than just repeat the tired tradition way these things are told. Communities are shaped by their landscape; their history has been shaped by their landscape. The landscape itself has been changed by their lives, by their industry; the actions of people in the Valleys have literally shaped the landscape around them, so they’ve got a very interesting connection to the land. It’s a timeless and extraordinarily beautiful landscape, and King Arthur was said to have passed through Gelligaer common, which is located immediately above the school.

There are many myths in South Wales that connect to the Arthurian legends, and there is a sense of the land holding all these stories, all these histories, but it’s changed so much and now these boys are living in a moment where their fate looks so different from the fate of their grandfathers because of the way their worlds have changed. Bringing in the grandfather I hope gave this sense, because he was able to share his perspective on how things have changed, and how his grandson’s life is different to his was when he was his age. You’ve got this really interesting moment where, because they’re not going to be sent down the pits, these boys have freedoms in some ways that older generations didn’t have, but they’ve lost some of the certainties that those older generations had, so it’s not as simple as saying it’s either good or bad. It’s complex.

King Arthur discovered his destiny and achieved something unexpected, and he did that with the support of Merlin as a role model, and I was interested in role models for the boys and who they look to in their lives, and one of the boys discussed frog hunting with his grancha, and he brought that element to the character of Arthur. Then they took me to the Pit Pond which just happens to be the world’s most beautiful place – lots of young kids go angling there in the summer, and it was such a gift. It felt like the perfect connection between the world of the play and the real world.

There seem to be two opposing views on destiny in the film: the young ‘Arthur’ believes that ‘destiny wins your future and how you want to live’ whereas his grancha doesn’t believe in destiny and thinks that ‘what you get out of life is what you put into it’. Which side of that debate resonates with you most?

I’d have to side with grancha on that one! I think it is what you make it, and understanding that it’s in your control is really important. It’s positive if you can believe that unexpected things are possible, that change is possible, that there can be these moments in life where even someone with not many prospects or who doesn’t know who he is can learn something surprising about himself. But I also think that you have to understand the influence you can have over your own life. Of course there are circumstances that impact on our lives, but you always have a choice – even if you can’t choose everything, there are always things you can choose and exercise some control over.

You’ve given these boys a real gift in giving them this opportunity. They seem like directors in the making!

Arts and education have been whittled down to nothing, and these boys have never done anything like devising a stage production in their lives. We had this amazing moment when we’d been developing the story with them, and we came back one day with a script for us to sit down and read together, and the boys took it so seriously. It meant that they cared about it, and they felt like it was theirs, because they’d never have showed it the same amount of respect. They were so keen about finding their lines on the page, they gave their characters personalities, and were really invested in the story. I knew then that the whole concept was going to work because they’d made it their own.

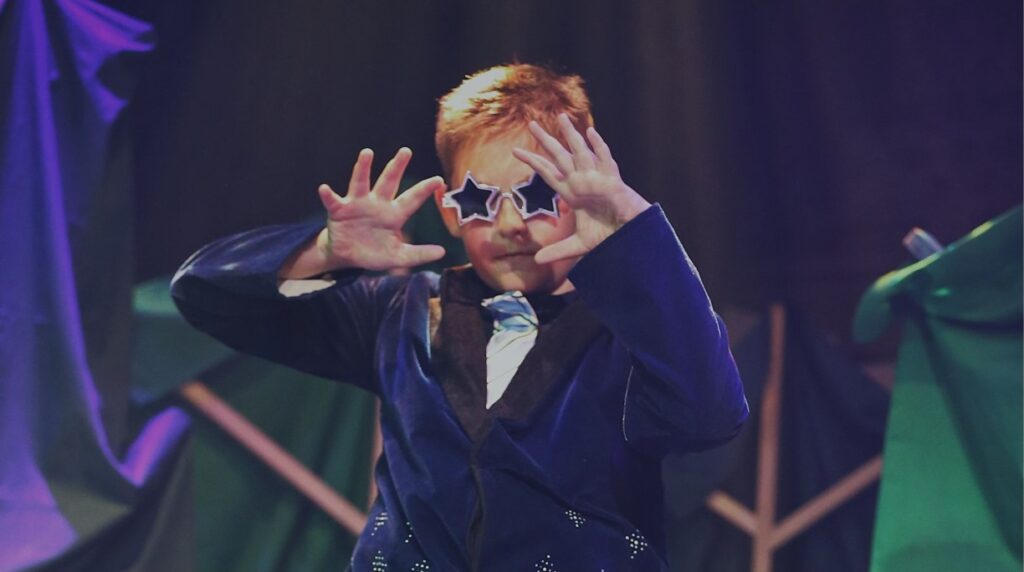

Some of the boys had specific skills, and we needed to channel them into particular roles. One boy was obsessed with drumming and he never expected them to get a beautiful orchestral timpani drum from the RWCMD, but we did – we really invested in where their areas of curiosity were. They were drawing their own costumes and we brought them back made as they’d specified. One boy took a while to come out of his shell. He was one of the shyest boys at the start, and then he turned up on the day before the performance with a remix he’d composed on garage band, specifically for particular moments in the story. Giving them an experience where they’d been taken seriously and their ideas had been made real, hopefully is a really positive memory for them, that they were taken seriously, they contributed, and were celebrated. The show was such a hit with the community and it was such a proud day for them. I hope it’s something they remember for a really long time.

There’s a real sense of joy and exuberance in the film, which I think comes from this particular way of working. Is this a method you’ve used before?

I’d never combined theatre and film in this way before, so I took a chance on a new way of working; something I’d been curious about for a long time but hadn’t done in exactly that way. I knew that it had to be a positive story, as it was genuinely my experience of that community. They’re used to having a lot of lazy journalism that repeats negative stories about the valleys. When they found out we were going to tell something positive and creative with the kids, they were so accommodating and supportive. I’m interested in not repeating tired, narrow judgments of what communities are like. It’s a close community, and those children are adored by their families; they’re living in a little bubble where they are safe and can explore both their landscape and their imaginations. Before life gets a bit more complicated for them, there is joy in their lives, and there is something lovely about where they live and who they are.

Was the school already putting on an Arthurian play or did you approach them with the idea?

I approached them. I had supported another director on a project a few years ago who had worked with the Head4Arts organisation. So Head4Arts introduced me to Caerphilly Borough Council, who then introduced me to the parents’ network, who introduced me to the school – the parents’ network knew the schools very well and had an idea about which schools would be up for it. After I won the commission for the film, I sat down with the team at Idris Davies [primary school], and then I applied for a specific strand of funding (which no longer exists) for collaborations between schools and artistic practitioners from Arts Council Wales. The Council invested money in the film too, and the Area Regeneration Team in Rhymney made that first step in investment, as it was positive for boys and looks for role modelling which they wanted to prioritise, as well as anything that would bring the community together. So, it started completely from scratch with me saying we want to devise this show with boys in the school, and make a film that tells the story and paints a portrait of the community.

What does Camelot as a concept mean to you?

Camelot is an aspirational place that brings to mind this idea of wealth, health, opportunity, safety, a sense of peace – but also it doesn’t exist. It’s a place that was spontaneously made by someone, and when we think about the idea of Camelot we’re thinking about how we could change the world if we could, and what kind of world we want to live in. Camelot is an idea, a utopia; where we would want to live and what that would look like. It’s a man-made kingdom that was an improvement on what came before. I’m interested in that kind of engagement, productively moving together towards building a better society. An idea like Camelot is a way in to that kind of conversation.

Camelot builds on the idea of the anthology being titled The Uncertain Kingdom – is Camelot that uncertain kingdom?

Yes – and if you’re sat in an uncertain kingdom, it’s where you might be hoping to be. It’s what you might be dreaming of while you’re sat in your uncertain kingdom. I suppose I wanted Camelot to be this moment of unbounded opportunity for these boys, a moment where they are safe, happy, free and unburdened by the world. This sort of perfect moment, when it’s summertime in the Rhymney valley, they’re hunting for frogs and they’re enjoying their childhoods.

How was the anthology put together?

The Uncertain Kingdom was thought up by three producers who were responding to the ways in which the political landscape felt last year. They wanted to empower filmmakers to make a comment on events and they wanted a fast turnaround so that the moment wouldn’t pass. They always intended to make 20 films; they reached out to 10 filmmakers and had an open call process for the other 10 – it was a really open brief, you just needed to pitch for an idea that would provide an insight into life in the UK now and connect with the questions they were asking about uncertainty. We had to write an application, submit a treatment once shortlisted and then pitch it in person. I understand that there were over 1400 applications, so it was really popular.

How do you think the experience will stay with you? How will it impact how you work in the future, the projects you align with?

I’m just thrilled that it worked! It was always going to be quite complex and difficult in some areas, so you have to accept that of all the elements you can expect one or two to be tricky. The only thing you hope for is that the tricky things aren’t in the important areas. I was lucky they weren’t. When it came to relationships with the boys and the community, there were no tricky areas; it felt like everything that really mattered went well, and all the tricky areas were in the boring financial areas. In a way, I feel like I got the problems I wanted.

You can never expect to make perfect work and I’m still learning a lot, but what I’m satisfied with was the tone of the film. The approach was what I wanted it to be, and the heart of the film was where I wanted it to be. It gave me confidence that it’s possible to connect a theatre project with a film project and tell a story that weaves between an imaginary world and a portrait of the real world. I want to make films that are revealing of our society, but our imaginary lives are important and can be revealing in themselves; I’m interested in the kind of documentary that wraps around something that might be imaginary, so I’ve left with some confidence that that sort of project works, and that people understand what I’m trying to do when they’re watching it.

Part of you always thinks is this just in my head, but it’s lovely that what you’ve made has communicated what you wanted it to. I’m hoping to develop it even further and continue to work in that way for sure. It’s also made me really appreciate how important relationships are in any project, that the collaborators you work with are so important, and that you never make anything like that on your own. I’m extremely grateful: I worked with lots of people I hadn’t worked with before, had some fantastic collaborators, took a few risks, and I’m so pleased they paid off.

The notion of collaboration is so important in an age of lockdown, which can be extremely isolating. Is the arts sector having to change fundamentally in light of this – and is collaboration the answer?

I think it is, you have to be quite inventive now with how you find your support for projects. I’ve always had to resource my projects from a real mixed bag of grants, private help, and volunteer support. You have to think really creatively about how you get things off the ground now. In recent years there’s been a lot of attention on how you make things and who you involve and how you involve them, and it’s not just about what you come out with at the end, it’s about who is represented in that process – it’s crucial that people are trying to think about the methods of working as being as important as the outcome.

People are recognising that you can’t tell certain stories unless you involve certain people – if you’re talking about the experience of certain communities or people of particular identifies, there’s a very specific way you have to go about that. People are creatively understanding how the who is just as important as the what, and just how connected those two things are. You have to think on a case-by-case basis what a project specifically needs, and who would be interested in it. You’re having to work out who your audience is before you get going because you’re having to find support to make it possible. Private funding is going to become more and more important now with creative projects, and filmmakers/theatremakers are needing to become effective fundraisers in order to stay in the game. I think the relationship between business and creative industries needs to be a closer one. I’d love to see more public funding for the arts.

In the same vein as you discussed earlier, it’s not just about humanity coming out the other side of this, it’s about what keeps you going along the way.

And to remind us what we’ve got in common, remind us that it’s what we’re working towards, why it’s worth looking after each other in the first place.

Giving people control of their own stories, as you’ve done here, is one of the most beautiful and important steps so that we can make a better world. The optimism of your film is so necessary.

I really agree. If you can’t imagine it, you can’t make it.

What’s next for you?

I’m lucky to have a side hustle in producing projects that inspire me, so I’m helping Cargo movement right now. They’re a really inspiring company that’s making innovative teaching resources and exhibition design that tells new stories from Black history. Creatively, I’m writing another short film, and I’m working with a production company to develop the Camelot concept into a miniseries for TV, which I’m very excited about. It’s a long road, and it’s very early days, but I’m pleased at least to be having intentional conversations

Wonderful! Thank you so much for your time, Alison – it’s been an absolute delight to talk to you!

I’ve had a lovely time! I can’t tell you how lovely it is to hear you loved the film, and that everything came across in the way I hoped it would. It’s like music to your ears. It’s been a long process – we met the boys in May 2019, but I’d been working on it from January 2019, so it feels now that people are starting to see it. We had to wait a long time for people to see it, and now that they are, it feels like a lovely end to the process, and it’s such a huge reward when someone has taken from it as much as you have. Thank you so much, I really am grateful.

The Uncertain Kingdom is available to watch on demand from Apple TV, Google Play, Amazon Prime, BFI Player, and Curzon Home Cinema.

Alison Hargreaves: Twitter – Instagram – Creator Site