I’ve never seen contemporary dance live onstage. I’ve seen glimpses of it on TV – just enough to be fascinated, baffled, then fascinated again. My relationship with classical music is much the same. A simple melody can weave its way through an orchestra with astounding grace – but when a composer tries to tell a story, to my ears, the music lacks the vocabulary to express it. The artistic intent fades in and out, like a conversation half overheard across a crowded room.

My first experience of live contemporary dance was full of grace, but also not without half-heard sentiments. The first of four short pieces was Nikita Gole’s Écrit – it was my favourite. The story (a passionate affair between artist Frida Kahlo and her partner Diego) seemed disjointed, but the dancing was bursting with energy and full of feeling. With Frida in spotlight and Diego in silhouette behind a curtain, there was a striking visual contrast onstage. Another striking contrast: Frida begins with flowing hands suggesting a young flower in bloom, then, as she sheds petals from a rose covered headband, suddenly I felt wrenched forward in time. This was brilliantly mirrored by Diego, who opens as a painter slashing and swiping on a canvas, then shrinks into a rocking chair as a man whose days have all been spent. The story lingered on from there – Diego taking on a strangely demonic presence that I couldn’t understand – but the vivid imagery and gorgeously evocative choreography held me from start to finish. I’d see more of this.

Ed Myhill’s Why Are People Clapping!? tapped into a more primal, almost tribal energy with his piece, which hit its peak with a mesmerising succession of solo dances. The momentum ebbed with the persistent intrusion of sports related choreography, which, for me, was an unwanted distraction.

Anthony Matsena’s Codi was the piece I was looking forward to the most – bringing contemporary dance down into the dark of the Welsh mines promised to be a thrilling clash of different worlds. I was mightily impressed with the innovative use of lighting, which made a bare stage seem full and ever changing. The choreography, however, did not feel hard or harsh enough to emulate the desperate, dangerous lives of those brave mining men.

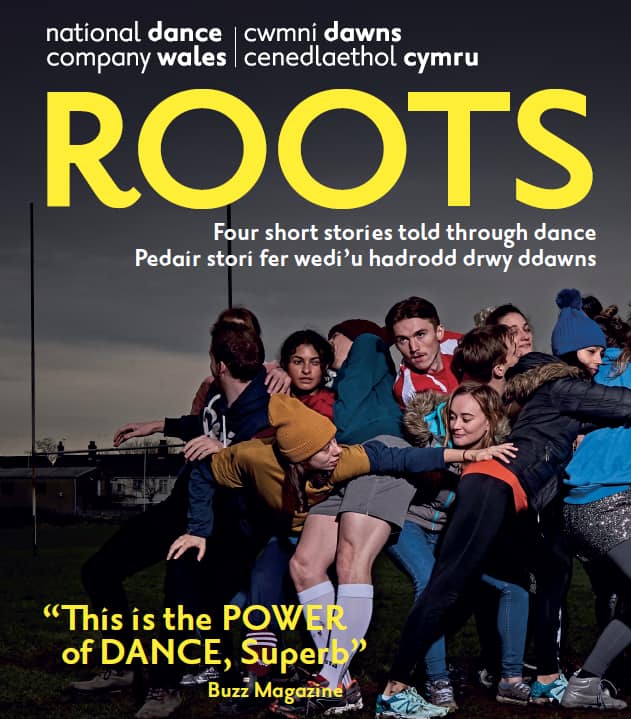

Last on the bill was Fearghus Ó Concchúir’s Rygbí: Annwyl/Dear, which likewise advertised an appealing fusion (this time, dance and rugby), but seemed to flit and fly around its subject matter without ever really going for the gut. With so many complex orchestrated movements to draw inspiration from, it felt like a missed opportunity that the geometry of the game was only intermittently recognisable.

What impressed me in every piece was the enthusiasm and athleticism of a remarkably talented dancing ensemble – the choreography did not always connect with me, but the pure intent of every performer was a sight worth seeing. And yes…it makes me want to lean in and hear more of what they’re saying, too. Next time!

Gareth Hall