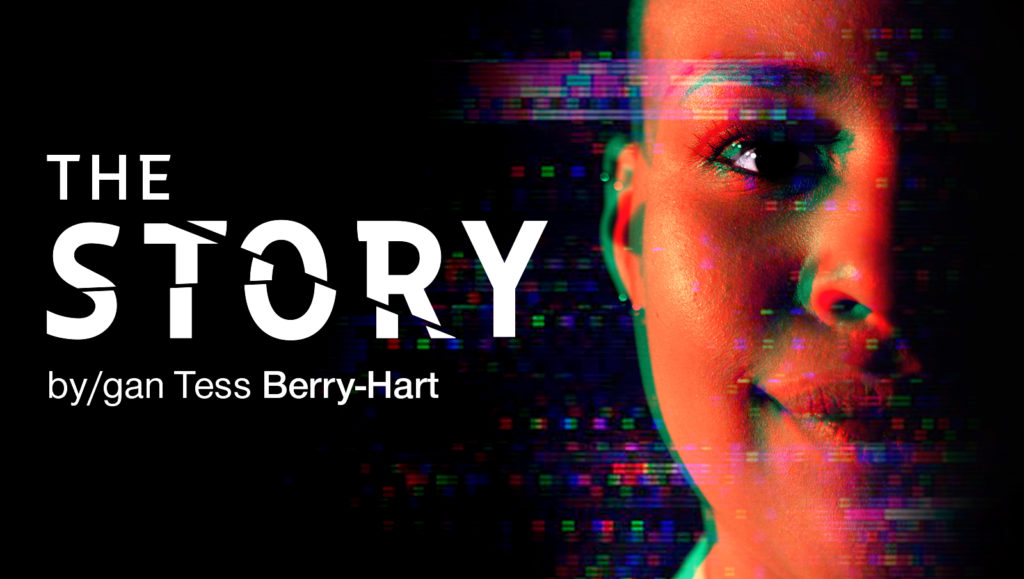

‘The Story’ by Tess Berry-Hart, directed by David Mercatali, presents as rather old-fashioned agit-prop theatre, here deployed as a perfectly legitimate form for holding our feet to the fire over the very unpleasant realities we so often choose to ignore around migration, detention centres, and the horrors of suspicion and injustice acted upon the dispossessed from wherever part of our poor and war-torn planet they make come.

As a theatre-going audience we are self-selectedly approaching the piece with a kind of generic left-wing sympathism, and this makes us a player in this drama. We need our eyes opened as one of the two character’s does. We need to see what Berry-Hart has come to see.

In a formula with which I was initially dissatisfied, the two actors present socio-political ideas through figures who are representative cyphers rather characters in any real, three-dimensional sense. One represents ‘our’ values as caring, middle-class, educated and informed liberals; the other represents all aspects of the oppressive state.

This is not promising. This seems like nineteen seventies’ student theatre. But it is not. It does become much more.

The piece is well presented and nimbly directed. Mercatali is determined that nothing here will lag. We are tumbled into darkness and action and, once in, we are fully immersed until the final line, the final beat. He manages the time lapses very skilfully, as he does the suggested violence and threat. This is almost always sure-footed and lapses are rare.

There are one or two clunky moments that obtrude stylistically, but generally the pace and intensity is right and skilfully delivered.

It is in the playing that we are most impressed though, particularly by the excellent Siwan Morris Hughes: there is an intensity and commitment which, in this tiny performance space, makes us feel voyeurs and brings awkwardness and discomfort – precisely what Berry-Hart most wants. Hannah McPake avoids all the major traps set for an actor with multiple playing: she ensures that changes from figure to figure are slight modulations of manner and little vocal nuances. She is always convincing – despite the writing at times, which provides her with half-drawn and unconvincing figures, quite intentionally – none of these people is real and we are never given the option of believing that they are. McPake’s playing then is technical, of necessity, whilst Morris-Hughes’ is fully immersive, deeply committed and very, very skilled.

The digital element to the piece is well-conceived and realised and enhances the work. The score is appropriate, though I felt that perhaps an opportunity was missed – I would have loved this to have been further developed and a more significant feature.

Although I initially felt detachment and disappointment in the piece, as the patterns of language developed, a poetry of oppression emerged, overlapping and building in intensity and rhythm and drew me in. Ideas became more complex and more satisfying. Some of the writing at the heart and height of the play is of a very high quality and Berry-Hart finds a poetry which does some justice to the huge issues with which she attempts to deal.

The ‘turn’ and ‘reveal’ doesn’t surprise us, but is built towards effectively and is dramatically pretty convincing – Morris-Hughes’ performance helps bring this off with its intensity and unflinching commitment.

The piece is leavened occasionally by moments of irony and humour, but it needed more. The horror and misery needed lifting at points and it is an extremely difficult thing to do – nonetheless, it needed doing. For me the play would have benefitted with the greater layering of perspective that this could have brought to what was too often a sledgehammer intensity in the writing.

So, I’m glad I finally got to see this work. Its retro’ agit-prop form contains and perhaps belies a complex, poetic work that is troubling and nuanced.