Young Critics, 3rd Act Critics and Kids in Museums volunteers are working in partnership with Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales (ACNMW) http://www.museumwales.ac.uk/ on a new free project focusing on the quality and standards of exhibitions and programming at their sites across Wales. Those involved recently spent a day with the staff at the National Museum, Cardiff. We will be featuring the responses to the day from the participants our last response is from artist Amelia Seren Roberts.

This blog post is reproduced from Amelia’s original blog which can be found at

AMELIA SEREN ROBERTS: IVOR DAVIES AND DESTRUCTION IN ART –

At the Natio… http://ameliaseren.blogspot.com/2015/12/ivor-davies-and-destruction-in-art-at.html?spref=tw

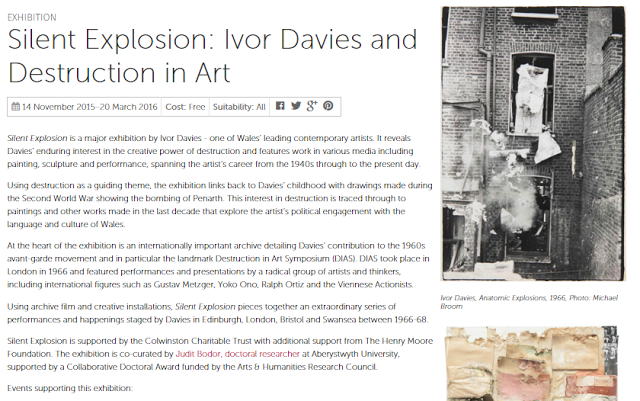

IVOR DAVIES AND DESTRUCTION IN ART

At the National Museum of Wales.

Curated by Judit Bognor.

I recently attended a tour of the Ivor Davies retrospective hosted by Judit Bognor, co-curator of the exhibition and tutor on the MFA at Cardiff School of Art & Design.

Judit began by explaining that the show was a solo show, rather than a group exhibition. In terms of curatorial practice, if the show is to contain different works by a group of artists, a topic or theme may be chosen before or after the exhibiting group is decided.

In this case, NMW was to show a retrospective of Ivor Davies’ practice. It is unusual for a gallery or museum to show a single artist’s work unless they are well-established.

The usual format of such retrospectives is a chronological one, starting at the early works and ending at the newer works; the intention of such is to show the development of an artists practice throughout their career. Other, non-chronological, approaches to displaying the pieces may include grouping by topic or materials.

In the case of Ivor Davies’ exhibition, the works are shown in reverse-chronological order, starting at the most recent works, and developing to focus on more early examples. The freedom Judit was allowed to curate with was partially due to the artworks being largely sourced from outside collections. When an artwork is in a permanent collection, the owner has say over when, where and how a work is presented, as such the curators input may be limited.

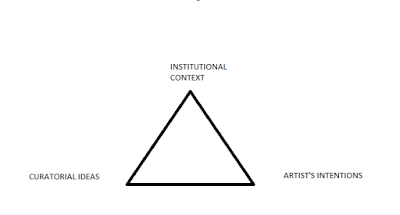

Judit drew attention to the relationship that exists between the artist, curator and institution when organising exhibitions. She spoke of the conflict often experienced between the ideas of the curator, the artist’s intentions for the work, and the institutional context.

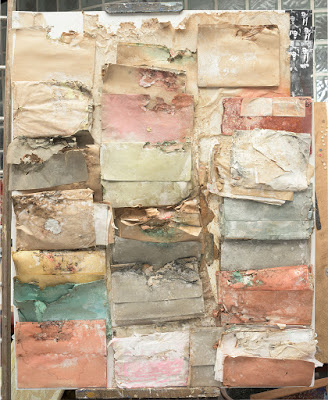

Judit expanded on the reasoning behind the title of the exhibition; a common thread that her colleagues and herself had recognised within the work over the whole of the artist’s career was that of destruction and creation, material transformation, and of durational thought. This was evidenced in works that developed during a symposium Ivor co-organised in the Sixties on the topic of destruction in art. Works related to the theme, as well as an archive of over 300 documents are shown alongside informative texts.

What interested me about the consistent theme of this exhibition was its relevance to a contemporary political context. A large number of the works having been created around the time of the Cold War, when the risk of nuclear devastation was a very real threat, the questions the works raise about destruction seem all the more poignant. Whether a deliberate comment or not, the timing of the exhibition, which coincides with Britain currently seeming on the brink of conflict, means that its concerns have become relevant once more.

It is important when considering whether an exhibition and the specific works within it require accompanying texts, the establishment within which the works are shown. It is more likely that simple, explanatory text in large print would be seen alongside works in a public museum, than would in a contemporary art gallery. This is because the curator must consider whether such interventions are appropriate in the context of the work and venue, and within this must select written supporting materials which suitably reflect the varying interests and academic capabilities of the reader. In this case, because the exhibition is sited at the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff, the audience is varied in age, ability and interests and thus large, simple explanatory text is appropriately shown in each room, whilst smaller texts are shown alongside specific works should the viewer choose to engage with the show in more depth. It is the viewer themselves in this case who decides their individual level of interaction with the show.

An interesting question thrown up by the curation of the exhibition is of how the viewer might experience a performance durationally. In this case, the curator has chosen to display a video recording of the performance, as well as a re-staging of one performance itself. Alongside this, an archive of materials surrounding the performance are exhibited which detail documentation of the memory of the event, instructions (or scores) for the performance, sketches and other ephemera.

Judit spoke briefly about the difficulties the team had experienced when considering how best to re-stage a historic performance in a contemporary setting. This is a topic that I have discussed once before whilst at the New Walk Gallery in Leicester, following their purchase of a performance piece by contemporary artist, Marvin Gaye Chetwynd. The difficulties in the conservation, and re-staging of a performance piece (especially a historic example) lie in the inability of the curator or institution to ever accurately re-create the exact context in which the work was first performed. Judit has approached this, whilst in conversation with the artist, by following the original scores of the performance, whilst adapting a proportion of them to fit more appropriately in to a museum context. Working in this way raises interesting questions about where the artwork exists and whether a performance work can ever truly be recreated or owned.

For me, the highlights of the exhibition include a painting by Ivor Davies which invites the viewer to ‘Ysgrifennwch graffiti prioddul ar fur y capel gyda’r sialc sydd yma’ (Write graffiti on the side of the chapel with the chalk); and in the archive, a darkly humorous newspaper article written by Robin Page entitled ‘Death and Art’ which cynically reports on an artform which involves the expressive act of stamping frogs to death whilst wearing a silver jumpsuit.

To see more information about the show, please visit the National Museum Wales, or take a look at their website here.